Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Royal Academy of Arts, 20 September 2025 – 18 January 2026

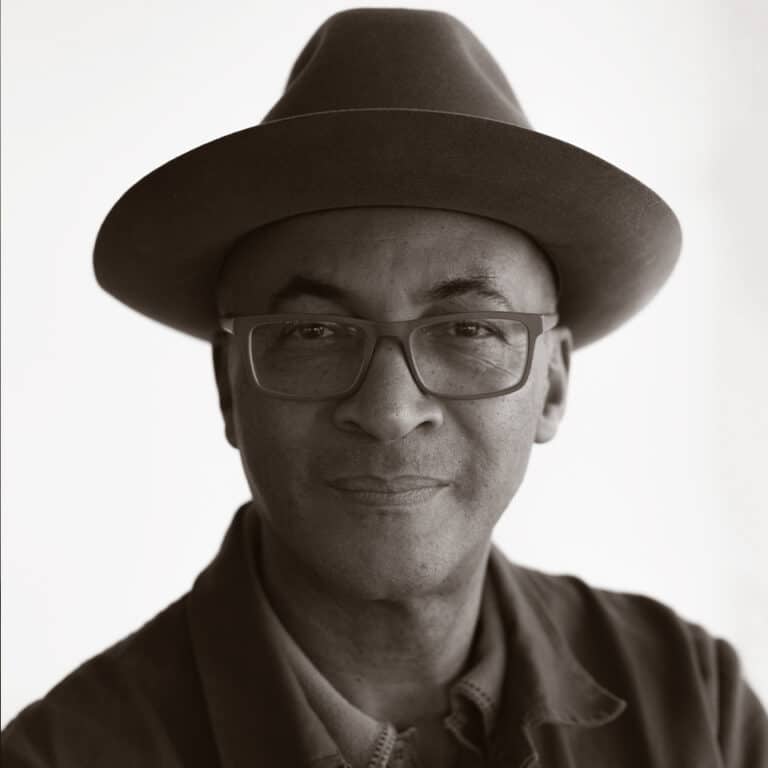

The African American artist Kerry James Marshall makes the invisible visible. He does so specifically in the depiction of black figures in his arresting portraits in The Histories, Marshall’s stunning new show at the Royal Academy of Arts, charting several decades of intense observation and application of his craft.

Marshall sets out his intention from the beginning with a series of large-scale works spurred on by, and in dialogue with, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952). That novel – the journey of a subterranean man who ends up living off-the-grid – is emblematic of all African Americans who were/are unseen by their white compatriots and it reverberates throughout the exhibition.

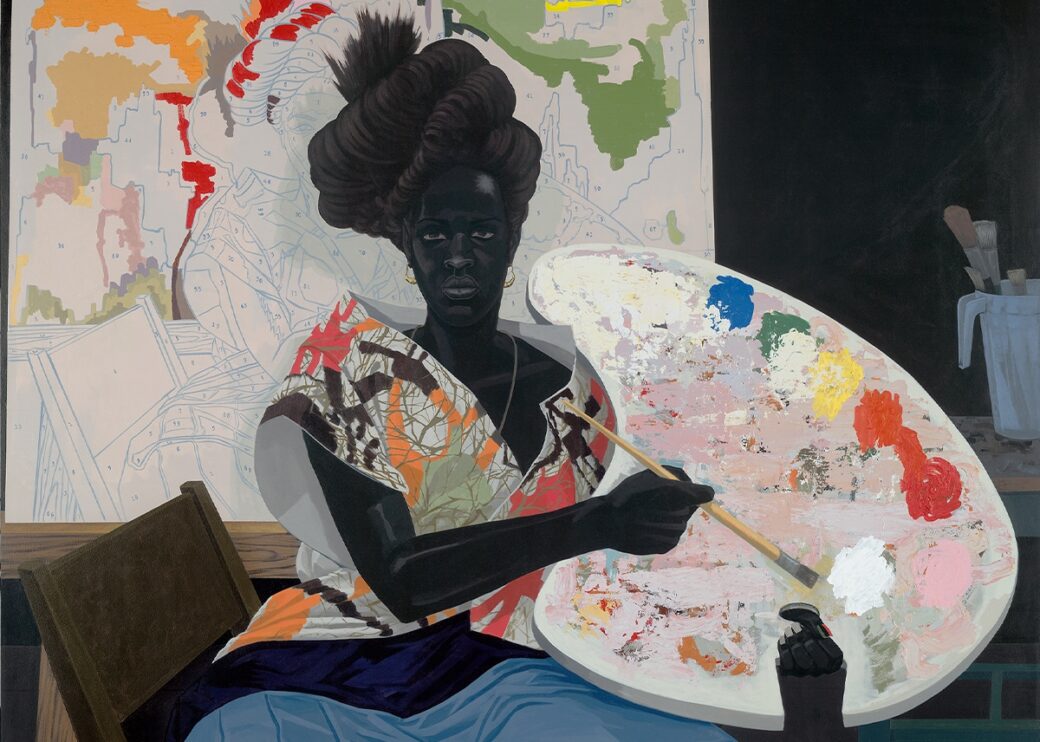

The attitude and tone of The Histories is marked by an unblinking defiance evident from the very first room. A jet black woman sporting an erect, elaborately braided ‘updo’ hairstyle, with an oversized, much worked palette balanced on her lap, sits warily cutting her eye at the viewer. Behind her is a canvas featuring the outline of a figure yet to be painted. The woman is meant to be ‘painting-by-numbers’ but it’s inferred that she’ll not be guided by the numbered sections. Old-fashioned and modern, she is both Marshall’s subject and his proxy, ready to defy convention and capture you as her subject. She’s difficult to read; the electrical charge sparking in her forehead speaks to Marshall’s fascination with the aesthetic of a Black Panther-ish comic-book. Initially, she seems to be jet black but look closely at her arms and you’ll see myriad subtle shades of black.

The received idea that black is a colour, denoting an absence of light with limited use, is complicated by Marshall, who shows that black can be just as rich and deep as any other colour. There are many different kinds of black in his compositions. ‘Mars black reads red,’ says Marshall, ‘Carbon black the darkest, deepest black is more like oil.‘

At his disposal are eight or nine variations of the colour black used to paint figures. Ordinarily, with such a reliance on a single colour, it wouldn’t be surprising if the characters looked as flat as cutouts or silhouettes but on Marshall’s canvases they have depth and heightened texture. The seventy-year-old master practitioner has spoken passionately about expanding the range of his palette by ‘changing the chromatic temperature of black’ through the addition of other colours: blue, red, green or violet.

Such variations challenge visitors’ perceptions. Uncannily, perhaps because I, too, am black, when standing in front of the canvases, I felt the works were completed with my presence. Indeed, in the exhibition’s catalogue, Marshall says he wants to ‘create an irresistible presence.’ At the Royal Academy of Arts, the paintings don’t just inspire a feeling of empathy but it’s possible to imagine yourself, Narcissus-like, peering in and falling into works that appear to be charged with your own reflection. Well, at least that was the case for me.

In ‘De Style’, you are right there, lining up to join the men at a barbershop, awaiting your turn for your ‘shadow fade’ cut. In this meeting place for the generations, with elders formally attired in their Sunday best suits alongside casually-dressed youth emblazoned with ornate knuckle dusters, you can almost hear the snip of scissors and idle chatter of men. Elsewhere, in ‘Souvenir IV’, you sit with the winged spirit of the deceased in the silvery grey, funereal living room before others arrive for the wake.

Marshall’s figures may be black but the canvases are often resplendent with vibrant colours, sprinkled with glitter, and punctuated by esoteric symbols and whimsical representations of musical scores that break the illusion of reality. The Histories also riffs on the history of art. In compositions such as ‘Past Times’, a satirical mimicking of the fantasy middle-class lifestyle of the American Dream, Marshall gives a playful nod to Georges Seurat’s ‘A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte’. In his update of the much-loved 19th century post-Impressionist painting, Marshall creates a tableau of black people at leisure around a lake with a social housing project in the distant background: a golfer swings and sends the ball soaring; a young girl tentatively lines up croquet shot with a wooden mallet; a family picnics on the grassy banks of the lake where a cool, sunshaded dude in a speedboat pulls along a delighted water-skier.

The artist has often spoken of not wanting to be constrained by worthily revisiting the trauma of America’s long history of racial violence. Keeping to his word with The Histories, Marshall paints black folk into the frame, moving them from the margins, where they were previously found, to the centre, not fighting an old battle of exclusion but just saying, ‘we’ve always been here; come, take a look.’ Though some of his subjects seem to be engaging, they are not entirely inviting.

Unsettling portrayals – in which it’s sometimes difficult to see the individual beyond their blackness, their brilliant white piano key-like white teeth and the whites of their eyes – are a daring critique of racist tropes of the so-called ‘unknowable’ black American population. But the paintings also risk a misunderstanding of Marshall’s intention by reinforcing a damaging stereotype, possibly inadvertently. There’s a coolness to his approach that is unafraid of ambiguity. Marshall has made clear that he’s not putting his soul on the canvas but the end product has a lot more emotional depth, even if obscured, than appears at first glance.

There are flourishes of biography amongst works referencing historical flashpoints, such as the Civil Rights era. The fragile idyll of a new complex of affordable social housing in Los Angeles, to where Marshall’s family relocated in his childhood, is conjured by ‘Watts, 1963’. The painting hints that the Arcadia of the communal gardens, in which the young Marshall plays, foreshadows the Los Angeles Watts uprisings that would break out two years later in 1965, resulting in thirty-four deaths and more than a thousand injuries, and which saw much of the area go up in flames, with many buildings burned to the ground.

The Histories does not protect visitors from discomfort but rewards them for staying the course. There’s something brutal but tender about ‘Could This Be Love’ that characterises the best of Marshall’s work. A couple, in a room as quiet as a confessional booth, strips off in anticipation of sex, with the woman raising her red dress above her head, looking directly at us, daring us to invade her privacy whilst accepting our voyeurism. At first, she appears to be nude, but with time our eyes adjust to the fact that her black underwear blends with her black skin. It’s a facet of an exhibition that entices viewers to slow down and wait lest they miss the subtle reveal.

Kerry James Marshall is an artist of enigma. His paintings preserve the mystery of the souls of black folk, skewering the lie rendered by white artists throughout modern history that portrayed black people as objects rather than subjects. His uber black portraits project variants of blackness while rejecting the old racial hierarchy which elevated lightness of skin colour; so that the people on the canvases are no longer a divided population graded by a sliding scale of pigment. Marshall’s popularity rests in his extraordinary portraiture operating on a frequency that resonates universally, one that chimes with the famous final line of Ellison’s Invisible Man: ‘Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?’

Royal Academy of Arts: Kerry James Marshall: The Histories: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/kerry-james-marshall

The Jollof House Party Opera

A joyful, multisensory feast that immerses audiences as active participants in a bustling restaurant kitchen

Impulse: Playing with Reality

A mixed reality experience by Anagram that journeys into the ADHD mind

Steve

The film adaptation of Max Porter's novella Shy is not a story about middle-class adults rescuing troubled youth; the grown-ups aren’t okay

Anna Freud at the Freud Museum

An appreciation of Anna Freud's pioneering work as a child psychologist and her place in the Freud Museum, London

The rainy day has come

What are Caribbean nations owed with the rise of extreme weather events?

The seven lamps of writing

I write because I am, and I write because I am not

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps