The lorry

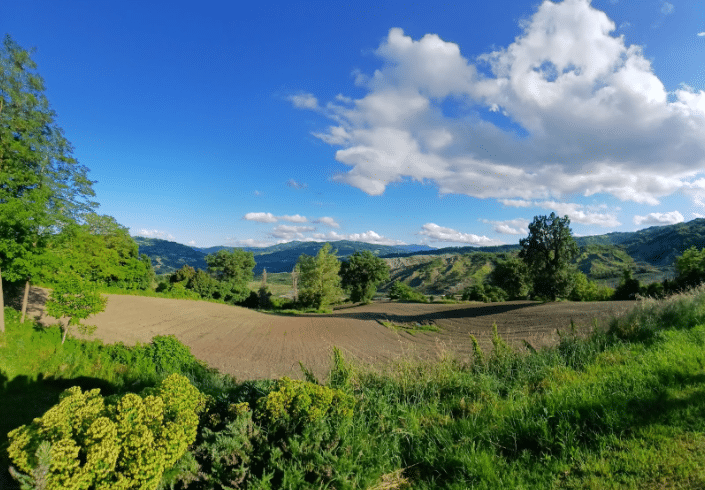

In the bottom of the valley to the south of the Villa Lugara, an old blue cargo lorry sat parked in amidst some unruly clumps of shrubs. Its doors were flung open, as though it had just pulled up. It was about a quarter of a mile from where I stood: not far, yet cordoned off by the banks of long grass that encircled the fields round about, grass in which unlucky walkers had been known to pick up small, blood-sucking stowaways: Ixodes ricinus, the disease-bearing castor bean tick. So instead of walking down to the lorry, I stared down at it from this fixed distance, wondering who had left it there and why they had not closed the doors. The lorry sat like this for two weeks, unvisited, as far as I could tell. Every morning I got up and wondered if someone was going to move it, or if I might see some labourers gathering something to throw in the back before finally driving it away. But no one came.

In the 1980s and 90s my grandfather had a big Ford cargo lorry. Everyone in our southern English village knew Grandad was coming by the distant sight of his truck. He arrived not in the form of a man, but of a forty-foot metal machine with a growl like the roar of some relict ancient species. This chimed with the central conceit of my favourite TV show, whose characters were humanoid robot soldiers able to shape-shift into powerful vehicles. Their leader was a heroic general with a Latin name, weary from endless wars, yet doggedly sticking to his ethical warrior’s code like a sort of cyborg Marcus Aurelius who spent half his time disguised as a lorry. Grandad was a fighter of a different kind, known for fearlessness in the sorts of confrontations that happened in lay-bys, builders’ yards and the car parks of local inns. When my mother was a baby, he did six months in Brixton prison for hitting a policeman who had come to break up a scuffle outside a pub. ‘In the general melee I ended up hitting him. Prison, Danes,’ he said to me, ‘It’s a time warp. I could have been in there six days or six years.’

I didn’t mention the lorry to any of the people I was staying with and, in spite of the fact it was quite plain to see from the rear of the villa, none of them mentioned it either. This gave rise to the thought that I might be imagining it: what if it was a phantom lorry, and my grandfather, a workaholic roofer and builder who always showed an interest in my writing, had driven it here from the afterlife to make sure I was hitting my targets every day? It was a silly thought, of course, which is why it worked. I wrote with machine-like obstinacy and at the end of a fortnight had managed just over 15,000 words. This was down to more than just the escape from parental duties and other work. As at school and university, I was here by the grace of a bursary, and galvanised partly by fear of resembling the stereotype of the Gypsy hanger-on. Grandad would have approved of how my fellow writers and I got down to the task every morning, and generally kept on top of the great temptation to socialise away the daytime hours. He never returned to prison. When age forced him to abandon work, the lorry was eventually sold, and I never quite got used to seeing him emerge from smaller forms of transport.

A writer’s retreat is also a time warp. The valley where the neglected lorry sat became a scrying pool, in which strange imagined happenings took place without me having to force them into being. I already had an idea of the story I was going to write before I turned up at the villa, but I was unprepared for the way the place itself would conspire with me, supply suggestions, and help me to excavate memories. A lorry features heavily in the story I am writing, perhaps because I half-hope for an afterlife in which I jump up into Grandad’s truck a final time before we slam the doors.

The seven lamps of writing

I write because I am, and I write because I am not

In appreciation of Margery Allingham

Margery Allingham was interested in everything, from telepathic communication to murderous families with lack of self-awareness

In defence of Black History Month

Is it time to bring an end to the UK's Black History Month?

Steve

The film adaptation of Max Porter's novella Shy is not a story about middle-class adults rescuing troubled youth; the grown-ups aren’t okay

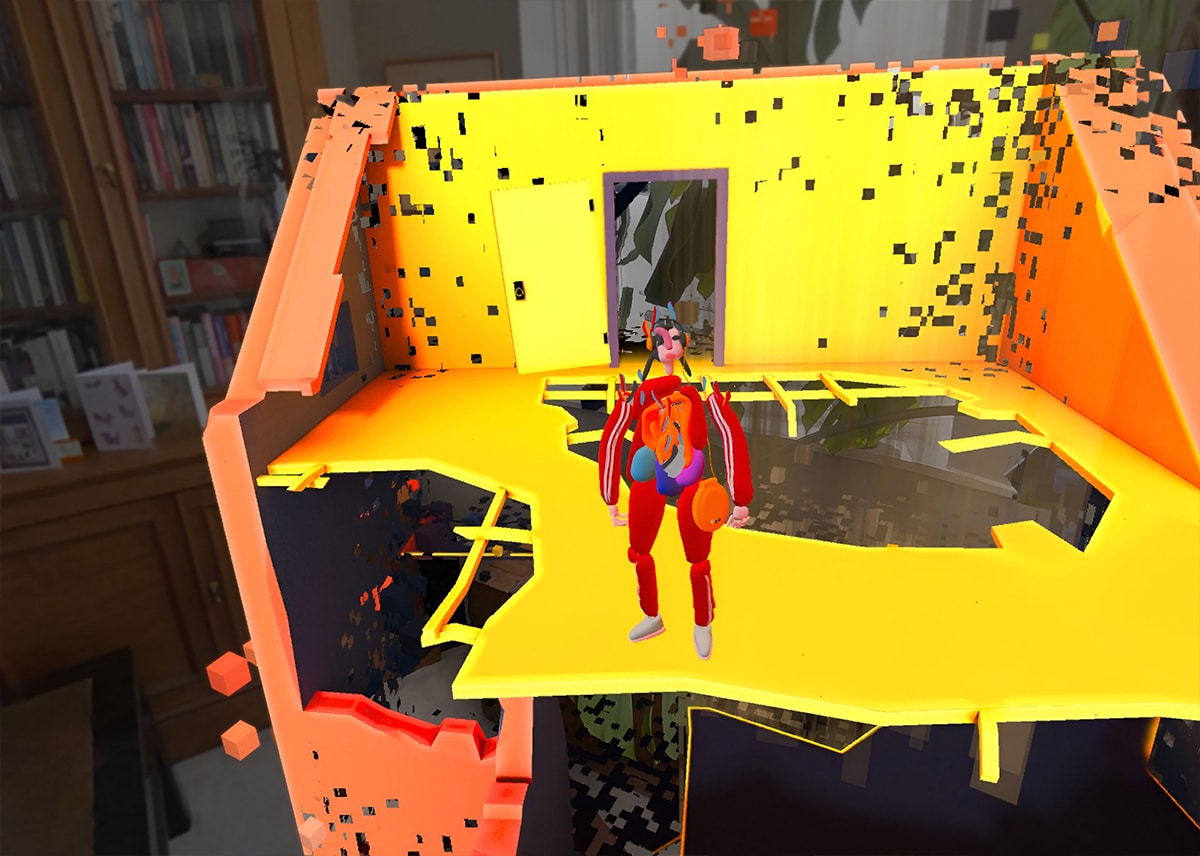

Impulse: Playing with Reality

A mixed reality experience by Anagram that journeys into the ADHD mind

Soon Come

In Soon Come, readers are treated to a narrative that has been, figuratively speaking, marinated in jerk seasoning

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps