Empire Without End

Imaobong Umoren

Fern Press, Penguin Random House, 2025

Review by Max Farrar

Dudley Thompson travelled from Jamaica to Britain to enlist for the Royal Air Force when the 1939-45 war was declared. The recruiting officer asked him if he was ‘of pure European descent’, a criterion set by the Army Council in 1938. Thompson answered ‘Yes,’ and suggested the flummoxed recruiter sent him for a blood test, commenting, ‘I think he gave up in disgust or frustration.’ Thompson then fought for the so-called mother country and later became a Pan-Africanist and a lawyer.

Imaobong Umoren somehow compresses 500 years of Caribbean-British history into around 400 pages of Empire Without End and on every page I learned something new, such as Thompson’s story. The exigencies of war, and active protests by Caribbeans in Britain and the West Indies, meant that the British dropped that racist criterion in 1939. Umoren’s thesis – that white supremacy is the dominant British impulse in its nefarious relations with the Caribbean from the 1500s right up to the present day – is well illustrated throughout this scintillating book by moments like that. Her scholarship is immense and her excellent footnotes are a cornucopia for keen students of this long period of racialised history.

Umoren’s book is particularly valuable in that it brings the Black experience in Britain and in the Caribbean right up to 2024. The sociological bit of me was particularly impressed that Umoren deploys a range of concepts that you don’t usually find in history books. Some historians rely on an exposition of racial discrimination and others take a class or gender perspective in shaping their narratives but Umoren manages to combine all of these. Her central focus is on the systematic and enduring development of a ‘racial-caste hierarchy’ throughout this period but she is just as interested in the role of gender divisions, and both ‘race’ and gender are always deployed alongside an understanding of capitalism and class.

Empire Without End is a genuinely intersectional history whose narrative is driven by the economic expropriation of people and natural resources in Africa and the Caribbean. It deploys a subtle awareness of the role of colourism in producing a pigmentocracy as enslaved people succeeded in their fight for freedom and a new ‘mixed’ class formation emerged in the Caribbean and then in Britain. Another merit of the book is that this is a dialectical history, emphasising that at every stage among all the population groups that the white Brits aimed to dominate and exploit – Umoren covers each of the islands they eventually controlled – there was a serious fightback, which in turn shaped British policy and practice.

In the early period of the book, Umoren writes that it is unclear whether the Spanish failure to grab the Eastern Caribbean was a result of Taíno resistance or because they didn’t think it was sufficiently valuable or perhaps it was both? We know that from 1495 Columbus gunned down both the Taíno and the Kalinago when he encountered resistance, and his successors were no stranger to unspeakable violence. My own research on St Kitts-Nevis, for a book about its favourite son, Arthur France, however, disputes Umoren’s view that Thomas Warner put down an ‘uprising’ by the Kalinago in 1625 or 1626: it’s more probable that he massacred them while they were asleep, making up a story about their plans to fight the colonists.

Umoren continues to remind us that the Brits started by suppressing the indigenous people, largely replacing them with enslaved Africans, and then faced more conflict from economic competition with its new colony in North America and a war on other colonising Europeans. Her class perspective is clear when she quotes the 1657 account of a British planter in Barbados, Richard Ligon, about the ‘wearisome and miserable lives’ of white labourers. (I would add that Cromwell had massacred the Irish at Drogheda in 1649 and the few he spared were transported to Barbados — the ancestors of today’s ‘red legs’.) Umoren continues to explore the ‘race’ element in reports like Ligon’s: he thought the enslaved Africans had a better life than the whites because they were better suited to the climate!

Citing the research of Professor Hilary Beckles, Vice-Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Umoren shows just how significant to the development of modern Britain was the enslavement of Africans and their hyper-exploitation on sugar plantations. In 1775, the value of the Caribbean plantations stood at £7.6 billion in 2024 prices. The triangular trade was, as Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery had pointed out in 1944, the basis for the prosperity of London, Bristol and Liverpool, and Umoren adds that Glasgow, Southampton, Lancaster, Plymouth, Preston, Dartmouth, Poole, Exeter and Chester all developed on the backs of enslaved Africans.

Economic issues such as these permeate Umoren’s book in a way that undermine her notion of the ‘racial-caste hierarchy’. Ever since Oliver Cox’s Class, Caste and Race (1948) the notion that people of colour (un)settled in the northern hemisphere should be understood in terms of caste has been under serious dispute. The sociologist Robert Miles has offered the more useful notion of ‘racialised class fractions’. Umoren herself repeatedly shows how, in the Caribbean and in Britain, mere skin colour did not totally fix a person’s social position. The economic and gendered position of each population group intersected with their ‘race’ in every period and some whites actually moved down the greasy pole while some people of colour moved up. Thinking in terms of a ‘racial-class-gender hierarchy’ would be a rather cumbersome way out of this problem.

In usefully bringing her story to the present day with an account of recent British history that has become a little better known since the #BlackLivesMatteer protests, Umoren deploys the insight of cultural studies’ professor Paul Gilroy that the loss of Empire has permeated Britain with a sense of ‘post-imperial nostalgia’. It’s a sign of Professor Umoren’s breadth of vision that she sees the plight of Britain today in terms of a deep unhappiness and discontent rooted in its racialised history. Only about 5% of British children, according to Professor Peter D’Sena, learn any detailed history of the Caribbean and its interaction with Britain. If the British government was serious about educational reform, it would insist that this book should be a prime source for a revised school history programme.

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

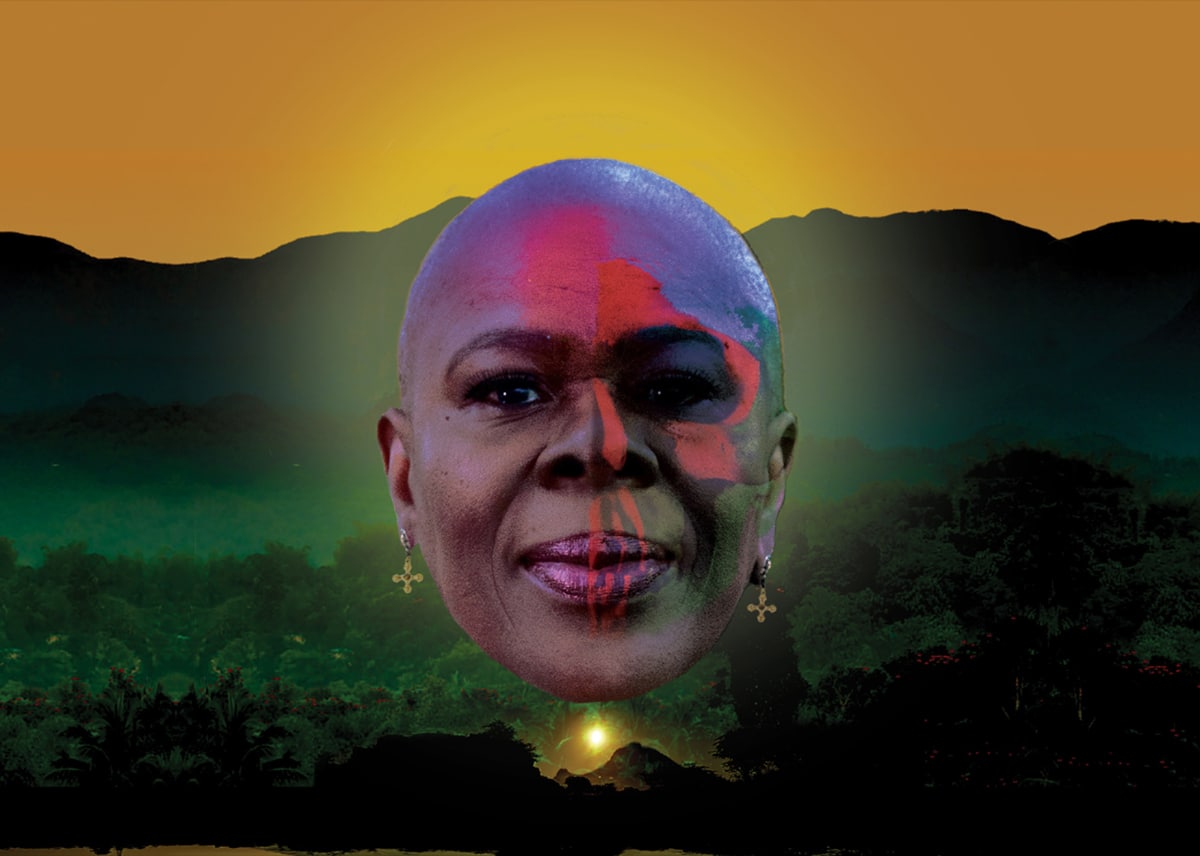

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

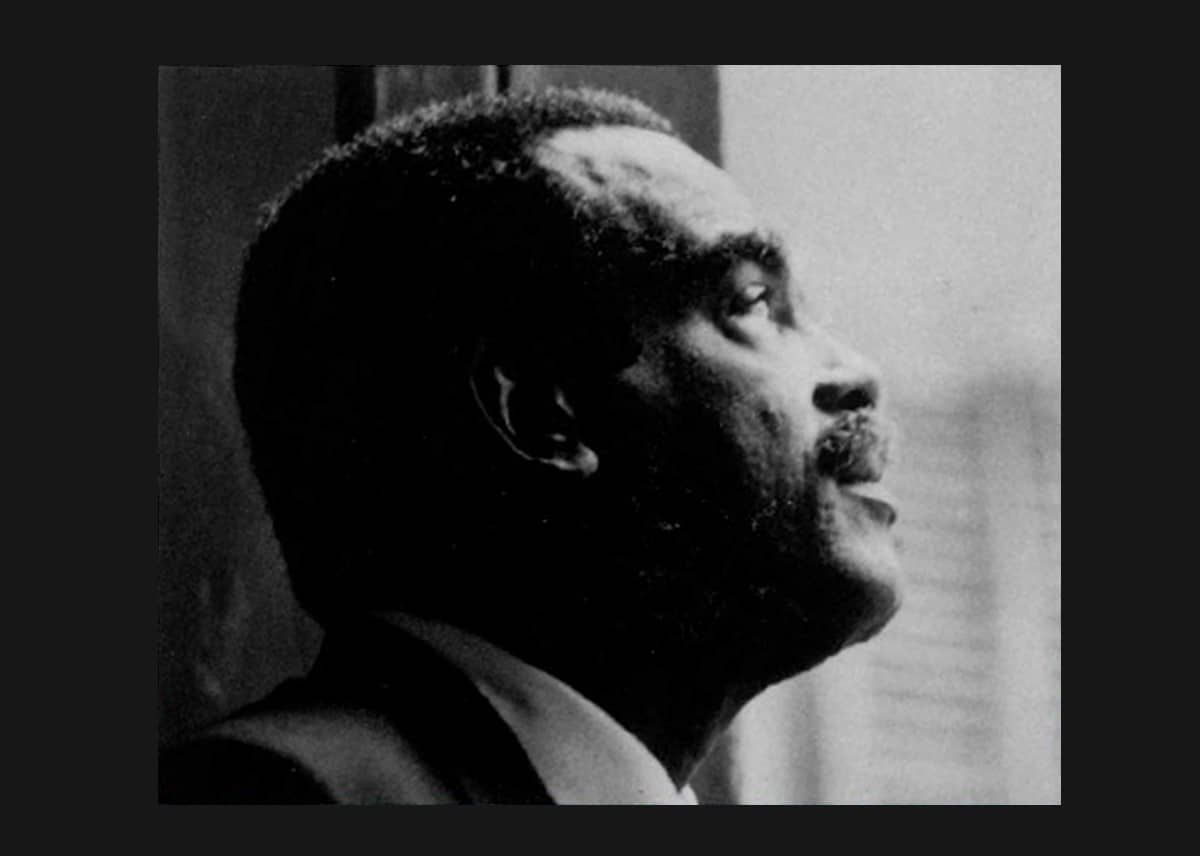

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps