Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed

Jacaranda, 2025

I can count on both hands the number of names of my family that also feature in Celeste Mohammed’s sophomore novel Ever Since We Small. That’s a rarity for me in literature, though not in Indo-Trinidadian life; we all know a Leela, a Shiva, an Anand.

Actually, the first time I ever felt ‘seen’ in a book was Earl Lovelace’s The Dragon Can’t Dance (1979). In it, there’s an Indo-Trinidadian man named Pariag who wrestles with feeling culturally isolated from those around him. That struck a chord with me, but that was about the only one. The rest of the novel, which I had been so thrilled to pick up as a young girl (I wasn’t yet a teenager and had just left Trinidad), felt like looking into my own home from the outside, just like Pariag.

My point isn’t to fault Lovelace – it is no author’s responsibility to be the voice of all – rather, it’s to reinforce the need for Trinidadian women’s voices in literature. In that light, Mohammed’s novel feels like a mirror held up to The Trinidadian Woman, reflecting her heart and her long-ignored stories. Ever Since We Small reads like an offering, as if to say, ‘Here is why it happen to you so.’

From 1899 India to modern Trinidad, Ever Since We Small unfolds as a ‘novel-in-stories’, like Mohammed’s debut, Pleasantview, which won the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature in 2022. Each story shifts from one character to the next but the pursuit of a neat resolution, so common in the English literary canon, isn’t the goal here. Instead, each character is a story. The histories they carry – often unknown to themselves but revealed to the reader – are quietly, devastatingly compelling.

It begins with Jayanti in India, the matriarch from whom every other character descends. She’s the first woman in the novel to say no, refusing to burn with her husband on his funeral pyre. From that moment, trauma begets trauma, which is carried through generations as the family moves from one systemic failing to another, across oceans and decades. In their still moments, they reflect on their ‘choices’, questioning why they feel trapped, insignificant, and lost.

Equally haunting are the choices yet to come and the seemingly inevitable consequences (or dare I say punishments) of seeking out happiness. What, after all, should a woman expect when she steps beyond the boundaries of her prescribed role? For one, it’s death by cutlass; for another, exile in shame. These are by no means spoilers, but inevitabilities. As one dead woman’s child puts it: ‘What allyuh crying for? Ent she always tell we this woulda happen?’

All is not so tragic. The novel’s title appears throughout, pointing to the far-reaching impacts of colonialism but also to the immeasurable stuff of life that binds the characters. There’s a tension between closeness and distance – a strained togetherness that, despite everything, endures. In their displacement and search for meaning, the island itself steps in as kin: trees hold power, hibiscus shows itself to be pruned, poui blossoms shower apologies.

Is the novel in the genre of magical realism? Most would be quick to say so, but Mohammed laughs at the label. In our ‘In Conversation’ WritersMosaic podcast, she explains that if she ever used those words with her grandmothers or aunts, many of whom inspired her stories, she’d be met with blank stares. ‘Magical realism is a craft term,’ she says. ‘But in Trinidad, it’s simply how life is.’ What others might use as a literary technique is, for Mohammed, a way of depicting reality itself and is the ordinary folklore woven into everyday Trinidadian life.

Ever Since We Small is both a critical work and a necessary voice in Trinidadian and global literature. Readers in Trinidad, and across its diaspora, will find so much of ‘home’ here, both the beautiful and devastating alike. What lingered with me, though, after I finished the book, wasn’t just a reader’s satisfaction, but a writer’s curiosity: if a book like this had existed far (far) sooner, might I have picked up the pen earlier than I did?

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny

The Booker Prize 2025 shortlisted novel is a beautiful exploration of love and loneliness between two young people

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

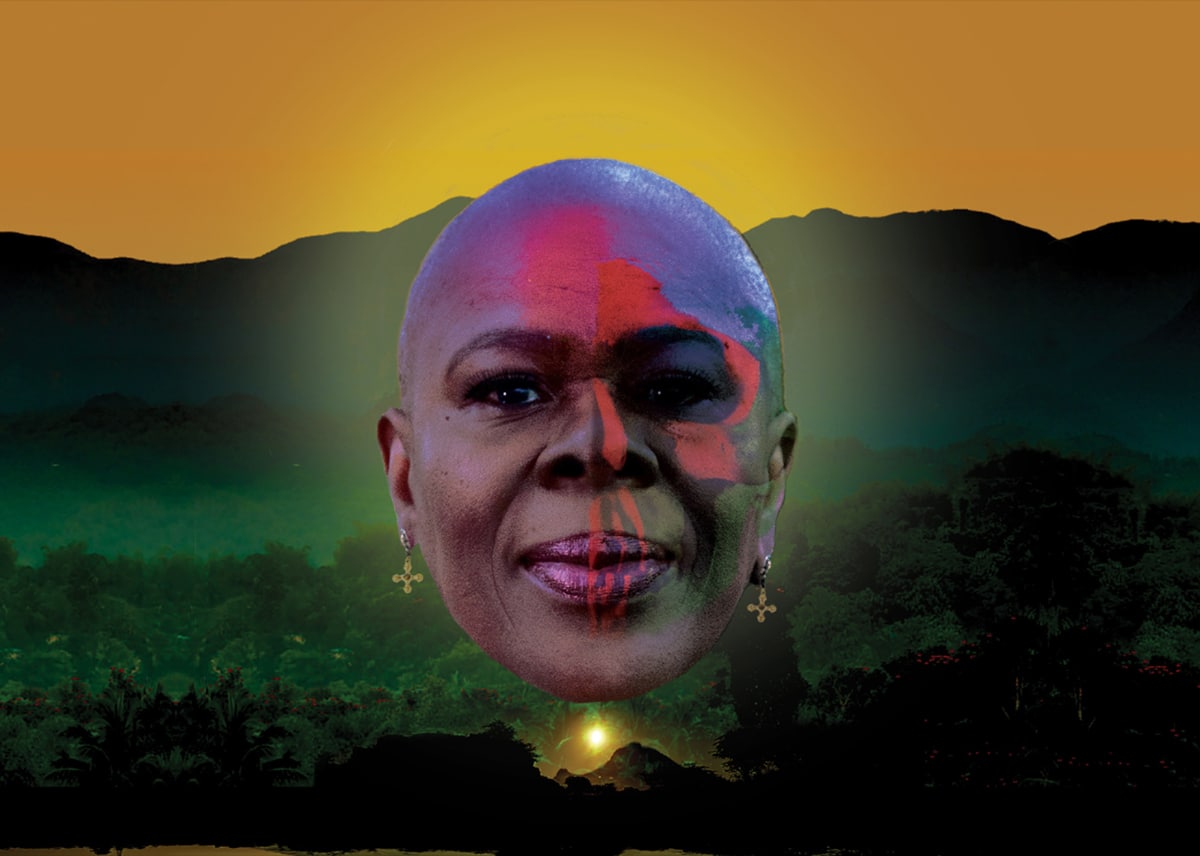

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

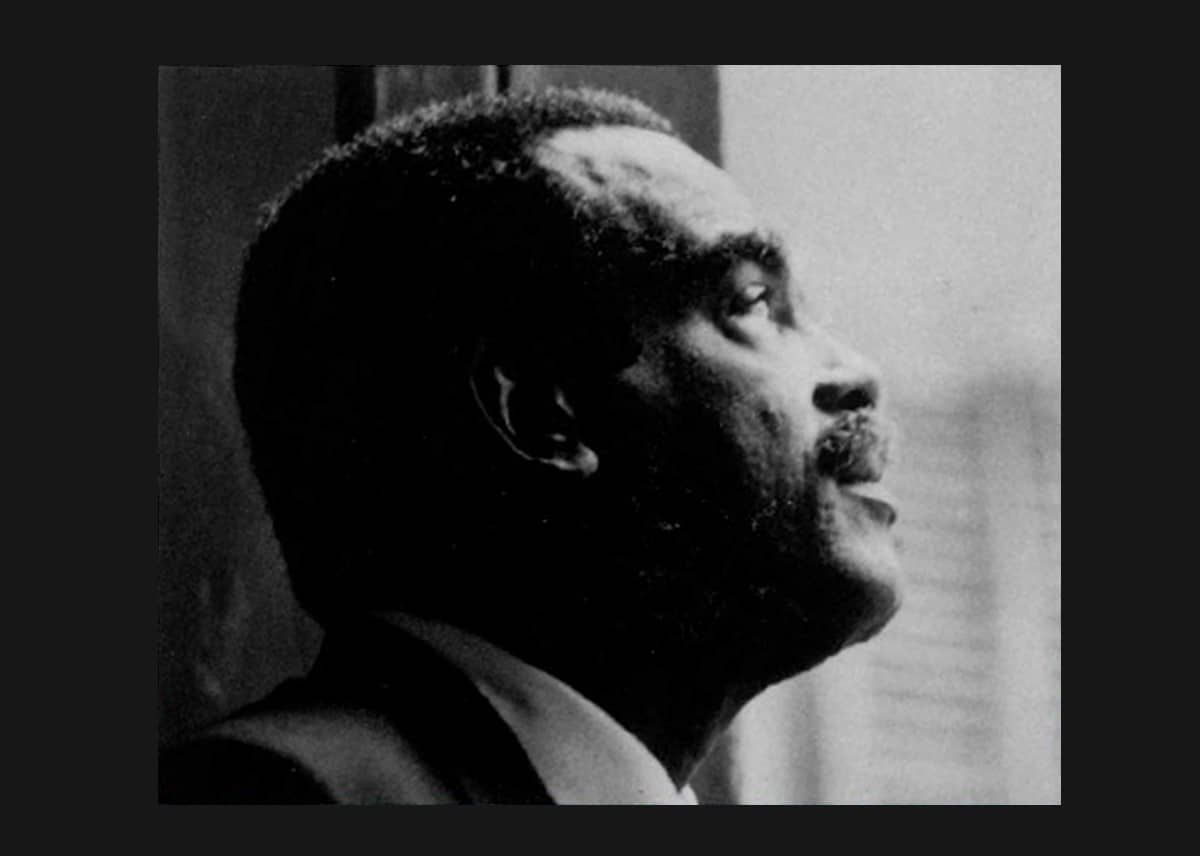

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'This new writing thing became part of my self-harming ritual. After I would cut, I would write...'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps