Frank Bowling: Collage

Hauser & Wirth, Paris

22 March – 24 May 2025

Review by Franklin Nelson

It feels apt that Sir Frank Bowling’s first solo exhibition in France has as its title an artistic term that migrated into English. Collage, at Hauser & Wirth, Paris, presents ten works that reflect his long-standing interest in how far paint can be put to work. They also explore collage as a conceptual tool. Bowling, now 91 and still making art from his studio in south London, was born in 1934 in what was then the colony of British Guiana, but in an interview four years ago he said that arriving in the UK capital in 1953 ‘felt like coming home’. ‘I’ll always be British but I also think of myself and my work as international. It’s a whole world thing’, he added.

This is a compact show, and yet it manages to be a ‘whole world thing’, spanning his range of colour and form and theme. This may be the first time Bowling’s work has travelled across the English Channel to appear by itself, but it feels at home.

The first work we see is also the smallest. ‘Back to Snail’ (2000) is evidently inspired by Henri Matisse’s ‘The Snail’. Asked by the magazine Modern Painters in 1999 to name the work of art that most shaped or changed his vision, Bowling chose Matisse’s bright, concentric collage pattern from 1953. Its title posits the French artist’s work as an anchor, but Bowling’s is collage of a different kind. Red and racing green strips of fabric, roughly triangular in shape and affixed to the canvas (a technique known as marouflage), coalesce unevenly around the edge and give way at the centre to a brighter square, from which emerges the mollusc. With orange-yellow whorls, its shell is more defined than in the Matisse. Because it is painted, it is also more textured, so that one can imagine reaching out to touch the ridges.

The other works in this first room are newer and stretch almost from floor to ceiling. In the lower half of ‘Orange Centred’ (2023), green paint, again laid on fabric, takes on hints of brown, blue and purple as it fans out from the left, like water in a bay, a thick yellowy-brown rim marking the shoreline. In the upper half, a lush interplay of pink, orange and yellow, evocative of an unruly sunset, is interrupted by a knotted piece of string in the lower right-hand corner. In the canvas’s dark middle, a paintbrush sits prominently at a right angle, its ferrule dirtier than its bristles. The artist might no longer be here, but he doesn’t want us to forget that he was.

Objects are absent from ‘Dancing’ (2023), which carries a vibrant charge despite the multiple shades of brown. They drip down the canvas in between lines of vivid green, but none is quite finished; all hover above the foot of the canvas, like an unhemmed curtain. Above a distinct middle section serving as another ominous border, climb streaks of paint that give rise to three thin, humanoid figures. They sway beneath fractal-like streaks of yellow in a warm orange sky, suggestive of another galaxy.

Upstairs in the gallery, ‘Ben’s Bar’ (2020) name-checks Bowling’s son. Lime green dominates here among darker splotches of the same colour, but the canvas’s most prominent constituent is a raspberry pink line that begins at the bottom of the canvas and rises almost to the top. Lines or bars make their presence felt in many works here, as if to insist on some order in light of Bowling’s self-devised tilting platform that enabled his ‘poured paintings’, emphasising process over subject matter.

After three works made in 2024 – ‘Water’, ‘Pallings 2’, and ‘Pallings’ – that speak to Bowling’s concern with borders and the shape of paint, the show’s final work, ‘Wadi √ One’ (2011) takes us back to the snail but also goes beyond it. Stencilled leaf patterns stand in for mathematical equations as three large pieces of fabric enclose a thick, textured strip of paint where colours – soft pink, golden yellow, olive green, berry red – run across and into each other. Their surroundings are still, but these shades feel restless, on the move.

Back downstairs is a room so small you might miss it. Yet the short film playing on the television inside is a must-see. ‘Frank Bowling in Guyana’ was shot by Tina Tranter in 1968 after the pair ‘cooked up this idea of going to Guyana to make a film about my childhood’, Bowling said in 2023. Scenes of island life – verdant fields, boys and girls in their church best, workers unloading cargo at the docks – overlay and run into each other. Well before the paintings on display were made, in the film orange-yellow tints push in from left and right as images move past one another, never quite allowed the time to conclude. The same is true of water, whether captured by Tranter in the day or at sundown. In her vision, the sea is as it is in the closing line of Derek Walcott’s Omeros: ‘still going on’. Fifty-six years later, Frank Bowling is too.

https://www.hauserwirth.com/hauser-wirth-exhibitions/frank-bowling-collage-paris/

Franklin Nelson

Franklin Nelson works for the Financial Times, commissioning and writing on UK politics, the economy and society as well as books and the arts.

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

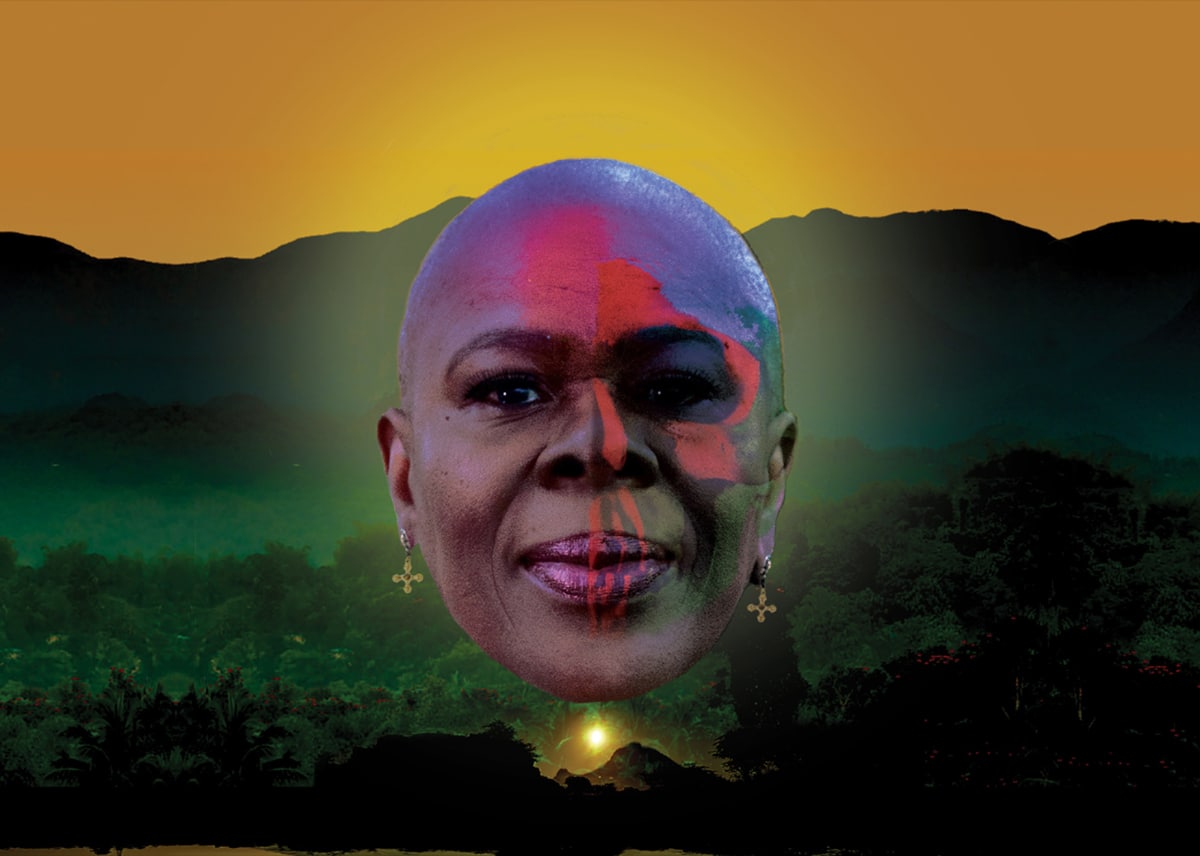

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

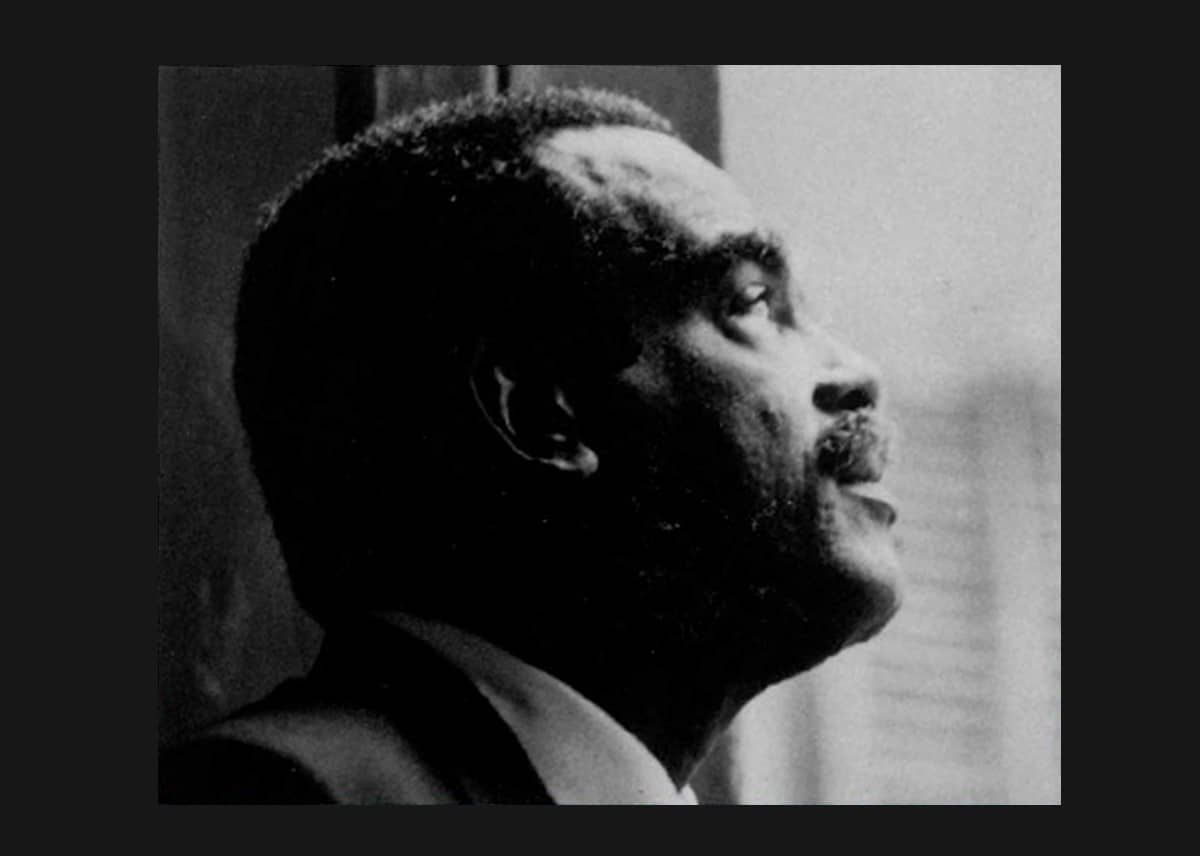

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps