Late Shift

Written and directed by Petra Volpe (2025)

Petra Volpe’s Late Shift is the Swiss writer-director’s portrayal of a nurse’s working day. The opening image is stark; a long line of nurses’ uniforms float mid-air, moving along a dry cleaner’s conveyor belt. The setting is severe, a Swiss hospital with wide corridors and concrete walls devoid of decoration. We meet our main character Floria, a nurse working one of the surgery ward’s late shifts, and are thrust into the action straightaway. From her first few minutes on shift, she is rubbing antibacterial gel into her hands to care for a vulnerable woman. Floria faces the challenge with a smile, but her journey soon spirals out of control. There are too many ill patients and not enough nurses on the ward. There are hardly any doctors present; most of them are performing surgeries or tending to emergencies on different floors.

The film is a relentless ninety minutes. We stay with Floria as she meets new patients, calms long-term ones, and makes conversation with their loved ones. Each exchange is pressured and short. There is always someone else she could, and perhaps should, be tending to. All the while she is interrupted by emergencies and phone calls from the surgical ward or the outside world.

There are very few pauses to breathe, the most striking of which is between her and an elderly woman. The patient wakes up, confused by her unfamiliar surroundings. Floria stops for a few precious minutes to sing her a lullaby with admirable care. A few hours later, under the mounting pressure, Floria loses control and screams. The moment is satisfying, yet sad. We have admired her strength, but her working conditions have made this reaction inevitable.

Late Shift tackles many of the issues surrounding healthcare service worldwide, from staff shortages and overcrowding to the disparity between public and private care services. Not all these problems can be explored fully, but the film’s intention is to show the system’s difficulties not to analyse them. One of the film’s greatest achievements is the development of its main character. We know very little about Floria’s life outside the hospital, and this makes for a more interesting film, as her nature is revealed through her actions. She carries sweets to give to a cancer patient’s children, she gives instructions in a positive but forceful tone, and she challenges doctors and patients with care. Leonie Benesch does a fantastic job as Floria, believably portraying a moral worker, doing her best under impossible circumstances.

The camera follows Floria closely, its movements matching her incessant pace. I felt as rushed and pressured as she was. My chest tightened every time an alarm was raised, or a patient approached with an unmet need. The one drawback of this style of filmmaking is that we cannot be equally impacted by every interaction. The pace and number of incidents become all too much. We are a bit numbed by the second half of the film and not every exchange between Floria and her desperate patients rings true.

The musical score is almost imperceptible for most of the film, reinforcing its thriller-like energy. Towards the end, however, a heartbreaking moment leads to a cheesy conclusion. A montage is underscored by the only song with lyrics in the film. This choice is a shame. It gives the film’s final moments a soap opera quality.

The film is not perfect, but it is an important one. There is a global shortage of nurses, and healthcare systems around the world are struggling to retain them. Workloads and working conditions are often unbearable. I celebrate Volpe’s decision to bring this story to life in such a raw and pacy style. Its original Swiss title, Heldin, translates to Heroine and seems fitting for what we watch onscreen. We all need reminding of the importance of nurses in our lives. Even I, a very healthy person, have deeply valued the calming presence of a nurse after waking up terrified in a hospital bed. Nurses are not just essential; their attention, treatment, and reassurance make all the difference.

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

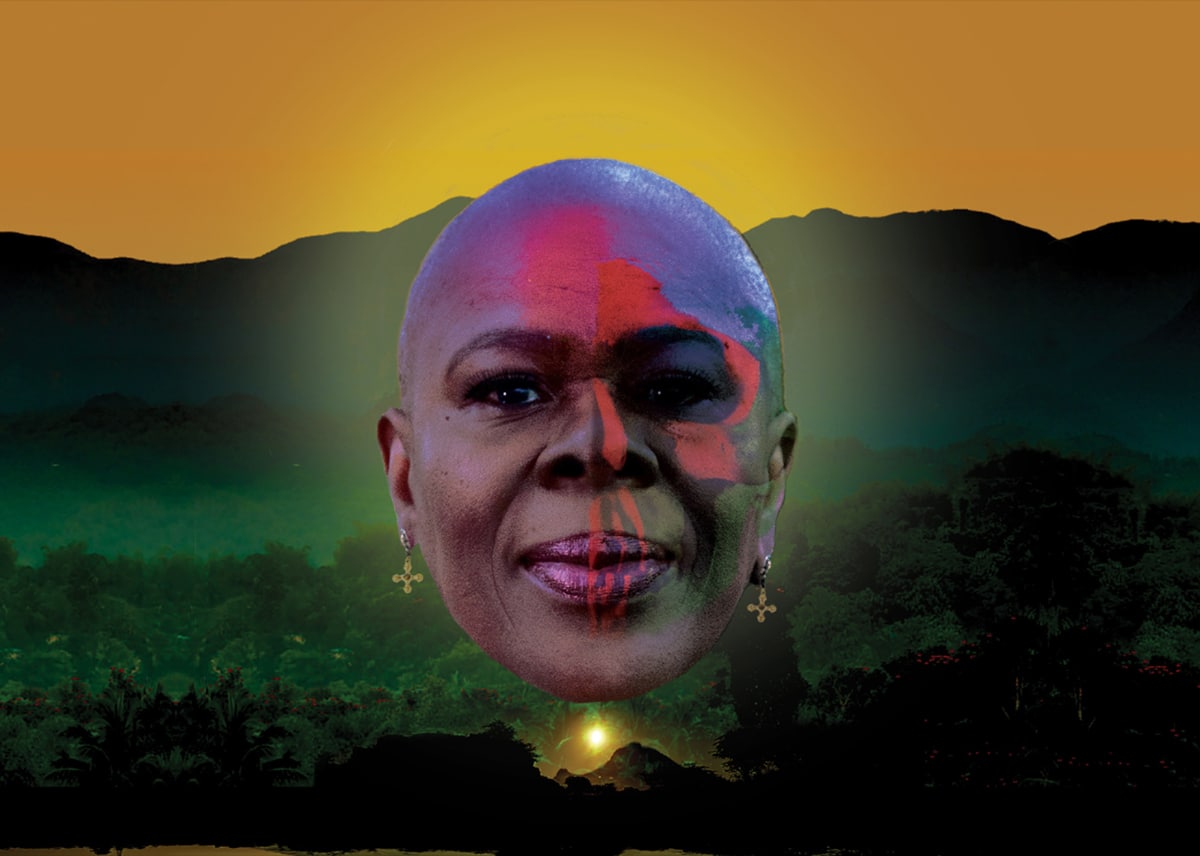

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

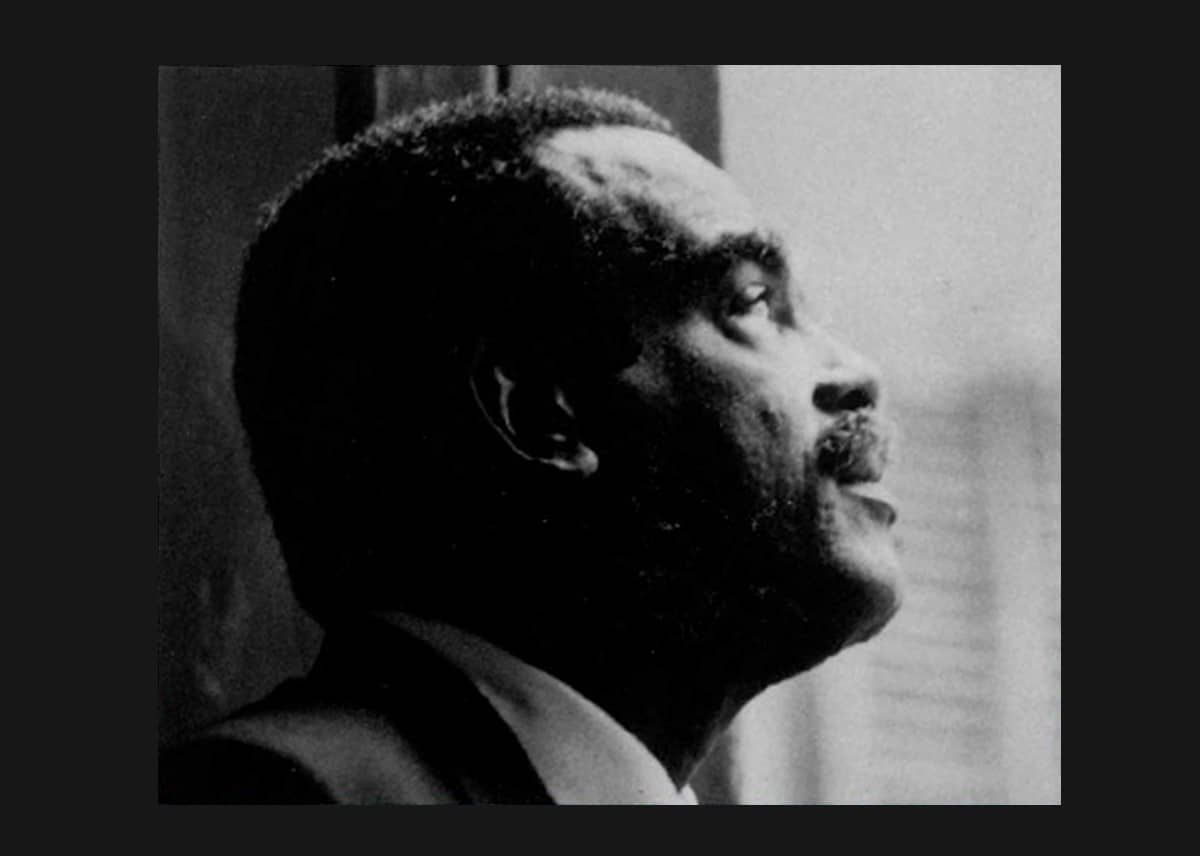

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps