Love forms

Claire Adam

Penguin Random House, 2025

I remember in school the practice of making us stand up, one by one, to read poems or prose passages, particularly from the novels of Charles Dickens, aloud to the rest of the class. It irked me at first; I wanted to read faster than I could speak and to be able, as was normal for me, to flick back along the lines and make connections between words and thoughts out of the linear sequence on the page – to see things from different angles. But then I started to hear the theatricality of Dickens’ characters speaking aloud, as though on stage, and remembered that Dickens was really an actor who took up a pen to make a living. And then I started to think about how odd silent reading was, and how recent a phenomenon. It was said that Alexander the Great read letters from his mother in silence, and St Augustine was astonished to see his teacher, St Ambrose, reading only with his eyes. It was always possible to read silently, but it was only with the development of printing, the spread of literacy (so you could read by yourself rather than have to listen to a handwritten sermon being read aloud), and the rise of a confessional literature in the form of the psychological novel — exploring an expanded inner consciousness linked to the agonised individual conscience of puritanical Protestantism — that silent reading was made normal. The pleasure of reading became private; so did the pain.

All this reflection about the rise of the novel as a space for private thinking and feeling came rushing back when I realised that, for me, the experience of silently reading Claire Adam’s Love Forms was one of immense and daunting loneliness. The novel takes the form of a searching, first-person account of the inner loneliness and emotional turmoil of Dawn Bishop, a middle-aged Trinidadian woman living alone in London, as she looks back on her life and copes with the limbo of the present. Her reason for writing is confessional, and its central focus is a search for the child she gave birth to in Venezuela as a 16-year-old, who was immediately and anonymously adopted away into the ether with no further contact. It was, she realises in retrospect, ‘a terrible mistake’, one that has made the loneliness she experiences in her life — as a daughter, as a wife and mother, and as a migrant from Trinidad to England — an all-consuming feeling of having ‘lost her way’.

The journey Dawn undertakes in finding her way back to her lost child and her own lost childhood is problematic at every level and for every relationship. Her husband only finds out about her first child from hospital notes during the birth of their child. She describes the pain of that second childbirth as a process also of losing touch with him. And again, that loneliness: ‘Once things really got going, I was on my own.’ Paranoia creeps in – people are whispering behind her back, sizing up her physical and moral lapses, both in her tightly knit family with its ‘pact’ of silence (one she feels gullible to have trusted) and in the wider community that, of course, ‘knew’ about girls like her. The stand-out voices in the book are Trinidadian – choric hallucinations speaking to her inner core.

The writing – Dawn’s process of putting words together to explain the past – is a form of healing, but is peculiarly also experienced as the birthing of an articulate consciousness that was not available to her as a child – ‘I wouldn’t have been able to use those words then’. This account of her past gives form to her experience in much the same way as an embryo forms into a foetus to be born as a child, before it too becomes an expression of both love and loss. Love Forms is a painful process to accompany, and a growing realisation of our capacity to love what we cannot hold.

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

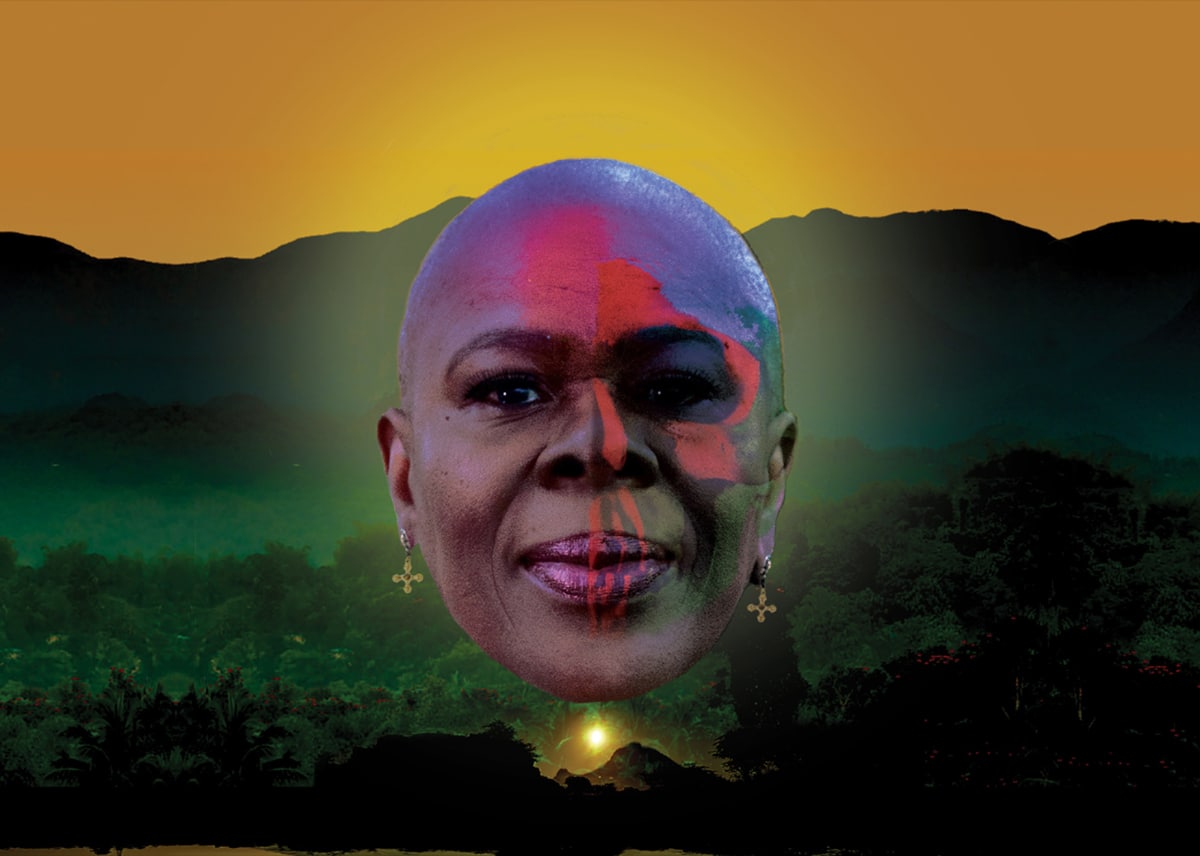

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps