Mahsa Salali: THE CALL: MUBĀH مُباح

From The London Open Live Performance Programme at the Whitechapel Gallery, 7 August 2025

Review by Sana Nassari

Upon entering, the scent of espand, burning wild rue seeds, hits me, instantly pulling me back to Iran. As my eyes adjust to the darkness, I see a set of chains hanging in the centre of the gallery. Around the space, naked double bass players with partially covered faces sit beside their instruments. An unusual hum, a textured, uneven white noise, fills the space, gradually morphing into the roar of fighter jets. Drawing on scent, sound, music, poetry, and movement, the performance creates a deeply immersive atmosphere that pulls the audience into its world.

The performance begins as the audience settles. A woman’s voice recites the adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, which is usually performed by a muezzin, making this an extremely rare occurrence. As someone who has lived in Iran most of her life, and heard the adhan daily, this was the first time I had ever heard it performed in a woman’s voice. At the same time, a blurred image of the artist’s body appears behind a curtain. Then, nude, the artist descends a staircase recalling a mosque’s minaret, from which the adhan is traditionally delivered. This is followed by an act of prostration (sujood) before Mahsa steps into the centre of the space, long chains draped over their neck and shoulders, pooling on the floor.

Mahsa Salali is an Iranian multidisciplinary performance artist, contemporary pianist, activist, and curator. Born in 1989 in Iran, Mahsa, like me, belongs to the Daheye Shast generation – those born in the 1980s, the first after the 1979 Revolution and the establishment of the Islamic regime. We grew up under the strictest newly imposed Shia–Islamic laws, either during or shortly after the eight-year Iran–Iraq war. The Daheye Shast generation has lived within an intangible yet all-encompassing trap for decades. Raised in a reshaped and enforced culture we resisted yet inevitably absorbed, we now wield elements of it in our struggles, as if it has become part of our very being. It is like a scar: a wound we hate and wish to remove, yet one that remains part of the body – a mark that must be shown to reveal the harm done, and sometimes to express the emotions it has shaped. In this show, the shifting tensions, concepts, and emotions symbolically capture the intense chaos experienced by this generation.

Before the performance began, we were given a letter instructing us to circle the centre – the artist and the chains – seven times, recalling tawaf, the pilgrimage ritual of circumambulating the Kaaba. This is a semi-immersive act: the artist inviting us into a shared circumambulation, turning the experience into a journey – one that inevitably draws our gaze toward the body at its centre. In this performance, the nudity, embedded in the ritual movement and the symbolic weight of the chains, is never presented as mere exposure. From the outset, it belongs to a sequence of ceremonial actions that redefines the body’s presence. By placing herself at the centre of our collective movement, the artist turns our inevitable gaze into a mirror – reflecting our own role in looking, objectifying, consuming – and then redirecting us toward questions about intimacy, power, and shame. This becomes a layer of armour for Mahsa, one that rebounds those questions back onto us, the viewers.

When the walking ceases, the double bass players begin tapping on the backs of their instruments – a gesture that itself challenges classical music conventions. This is particularly striking given Mahsa’s training in piano performance at Goldsmiths, University of London, and in performance art and contemporary piano practice at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance.

Mahsa then begins a mournful chest-beating, followed by the recitation of a lamenting Maddahi – a form of religious chanting in Shia Islam, most often performed during mourning ceremonies for the martyrdom of Imam Husayn. However, what Mahsa chooses to recite here is one of the most recent and controversial poems by Shahab-aldin Mosavi, which became widely popular during the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran:

I loathe your religion,

a curse upon your creed,

upon the sanctimonious calluses on your foreheads

and the hardness of your hearts.

O city stripped of its faith,

O people under a curse,

O world made faithless

by your disgraceful covenant.

By now, the double bass players are out of the gallery, in the hallway. The unusual hum that has been playing in the salon turns once again into the sound of jets, recalling wartime. Suddenly, the artist – their face full of tears and drops of sweat, body bruised from the clash of hands and chains – starts to dance, smiling, inviting us to join in with our hands while performing Iranian contemporary dance, a style instantly familiar to every Iranian. Turning all around the gallery, the body, flesh, skin, and chains unify; the wounds merge with their owner, colliding against agony, stillness, and passivity. Opening a way through the audience to the hallway, the artist wrings the 20 kg chains and sways freely like a feather – yes, like a feather separated from the body of a bird, from the whole, from a once-unified being, torn from its homeland, even lifeless now, yet still dancing.

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

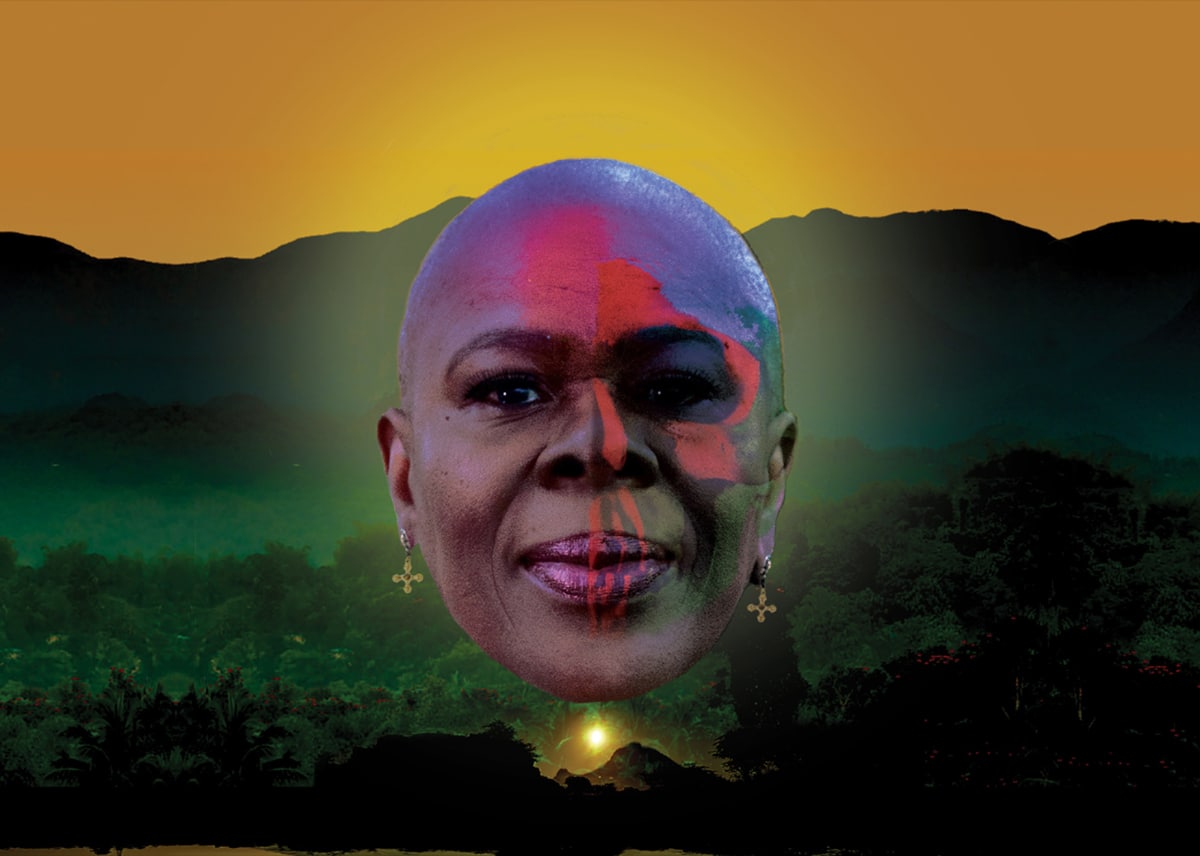

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

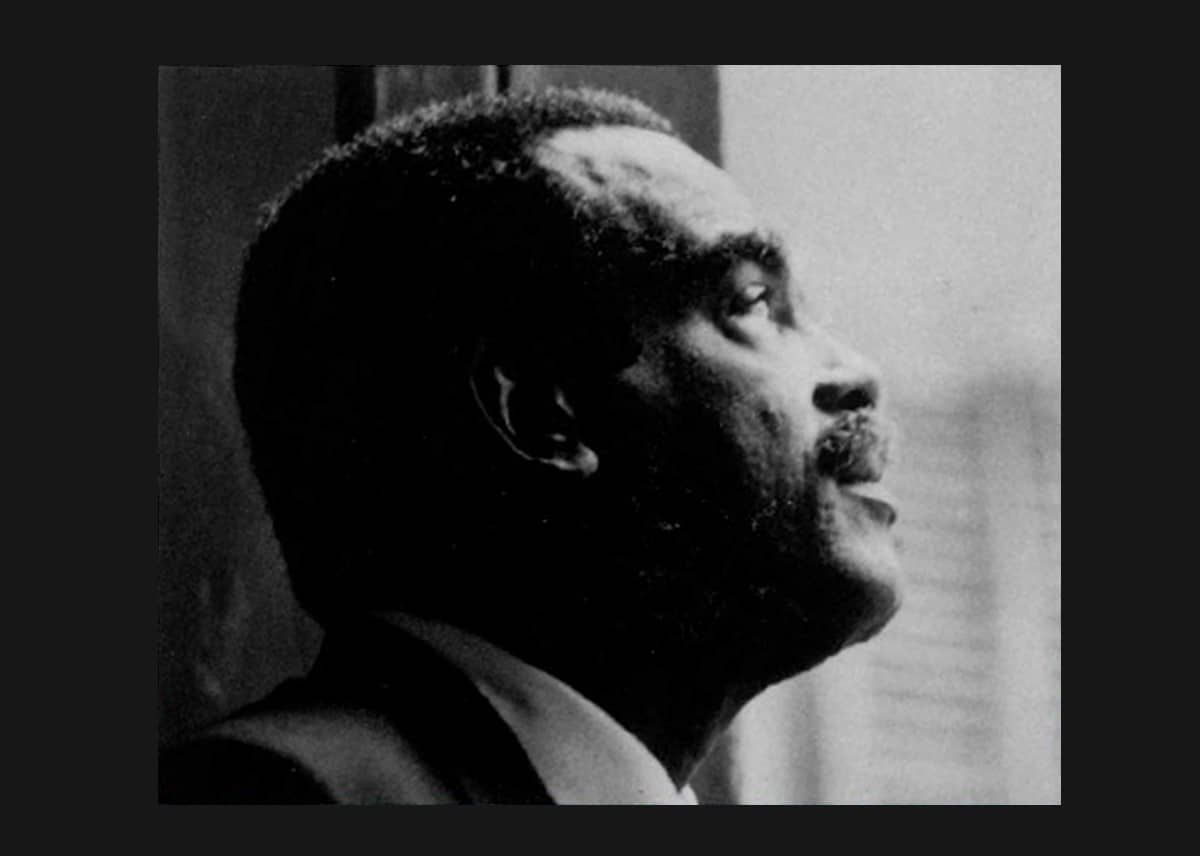

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps