The Harder They Come

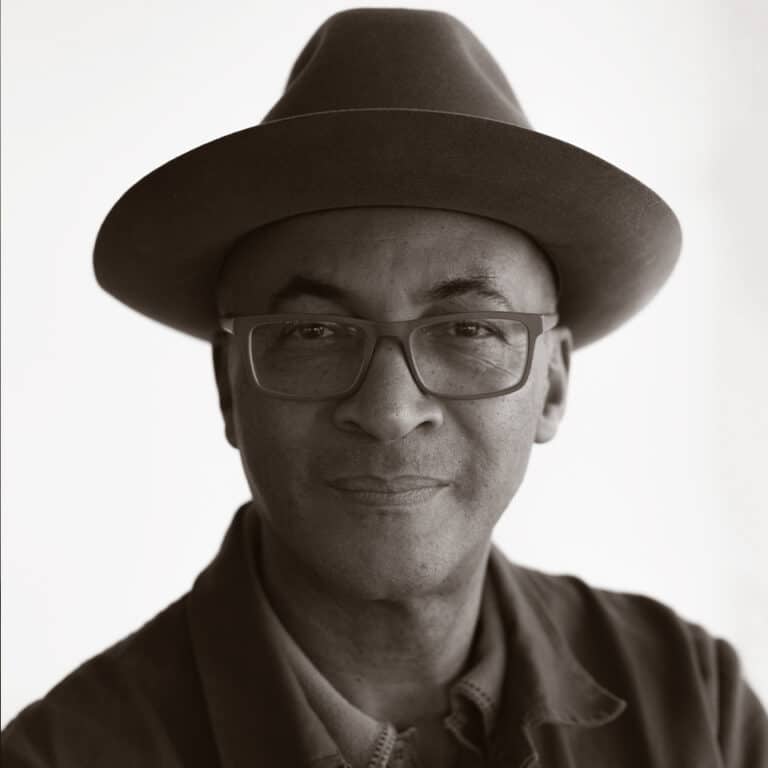

Adapted by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Matthew Xia

Based on the film co-written by Perry Henzell and Trevor Rhone, with songs by Jimmy Cliff

Theatre Royal Stratford East, London, until 1 November 2025

When Jamaica’s first feature film The Harder They Come opened in Kingston in 1972, there was such excitement that each seat in the cinema was occupied by at least three Jamaicans. Trevor Rhone, who co-wrote the screenplay with the director Perry Henzell, explained the reason for the enthusiasm to me: ‘The film marked a seismic shift in the people’s perception of themselves.’ Used to valorising Hollywood stars like John Wayne and Jane Mansfield, ‘Jamaicans now had their own local heroes as giants projected onto the screen. It was awesome!’

The protagonist Ivan, a mostly likeable antihero, was based on the infamous gangster Ivanhoe ‘Rhygin’ Martin. In 1948, the so-called ‘two gun killer’ terrorised Jamaica and mocked the police by miraculously avoiding capture time and again. In the film, Ivan, the criminal escapologist, has an additional talent. As he tells anyone who’ll listen, ‘I can sing, you know!’ And it’s true. Ivan, played by Jimmy Cliff, invites adoration and provokes outrage; at times he has the heart of a devil but the voice of an angel. The film made Cliff an international star and, featuring an extraordinary soundtrack that included the music of Cliff, Toots and the Maytals, Desmond Dekker and a host of others, introduced the world to reggae.

The Harder They Come has now been adapted as a musical, directed with unshowy confidence by Matthew Xia at Stratford East, with a text by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, who has also written three additional new songs. At its centre is a powerful and poignant performance from Natey Jones as Ivan, whose transitions from speech to song are spellbinding. Jones exudes boundless charm as the naive country boy who comes to town with his heart set on becoming a ‘star bwoi’; a recording star with a potentially chart-topping, soulful, reggae song. Set mostly in Kingston’s Trenchtown ghetto, the show’s designers subtly employ muted colours, and galvanised zinc roofs to conjure an empire of dust and dirt, with open sewers and ‘scandal bags’ for the removal of human waste.

A solitary uptown apartment, raised up on the second floor of a doll’s house-like structure with the facade removed, represents the tantalising possibilities of middle class life, separated from the poor, working class ‘sufferahs’ by an invisible cordon sanitaire. The only engine of any possible social elevation is to be found downtown at Hilton’s recording studio, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that talent will always win out. Only the cigar-chomping producer, played by Thomas Vernal, shuttling seamlessly between bonhomie and menace, can make a hit; and for good measure, Hilton can break you too, as Ivan seems destined to discover, as easily as cracking lice between his fingers.

All of Jamaican life is depicted on stage with thrilling simplicity: a projection on a diaphanous curtain transports us to the popular Kingston cinema attended by Ivan and his peers, who revel in Westerns in which the ‘hero can’t die before the final reel.’ Later, Ivan’s romantic bike ride with a girlfriend to the alluring coast is stylishly depicted through a projection on the same billowing curtain. Style! ‘Simple so,’ as Jamaicans say.

Style is all for the ghetto-dwelling ‘sufferahs’, especially the newcomer Ivan, who is desperate to impress and covets a tailor-made, black vest with a central gold star as a signifier of his eventual success. You can take away the man’s livelihood and his belly might be knocking on his backbone, but you can’t take away his style. Style also comes through the exuberant street language, originally captured by Henzell and Rhone and reaffirmed in the musical, in rich patois and ribald verbal jousting, brutal and bruising but also, occasionally, deferential to authority figures such as the local pastor, Preacher.

The musical is underscored by its raw, stunning authenticity, right down to the language and period costumes. Ivan’s increasingly flamboyant getup – floppy hat, sunglasses and satin shirt – is a projection of his ambition; the cast’s outfits, though, often disguise their inner unrevealed selves. In one stunning scene at Preacher’s church, the pious ‘amen corner’ choir suddenly rip off their white gowns and their churchified exaltations morph into unashamed, bacchanal slackness, grooving and grinding, scantily-clad in bras, boxer shorts and ‘batty rider’ hot pants.

The Harder They Come pits Ivan against Preacher, portrayed with delightful relish by Jason Pennycooke as a vain and prickly man with transparent insincerity. Both Preacher and Ivan are in love with Elsa (Madeline Charlemagne), whom the pastor ostensibly has been caring for since she was orphaned. But, as a laconic street hustler rightly warns Ivan, Preacher has been waiting patiently for his teenage charge Elsa to ripen and ‘when the time’s right, he damn well pick that fruit!’

The two suitors for Elsa’s affections are driven by disparate visions of the future rewards for a life of suffering, as is the lot for the majority of the island’s population. Preacher is a prophet of the hereafter whilst Ivan is the prophet of the here today; he wants his share of earthly spoils ‘here and now’, as he articulates in the title song, ‘But as sure as the sun will shine/I’m gonna get my share now, what’s mine.’

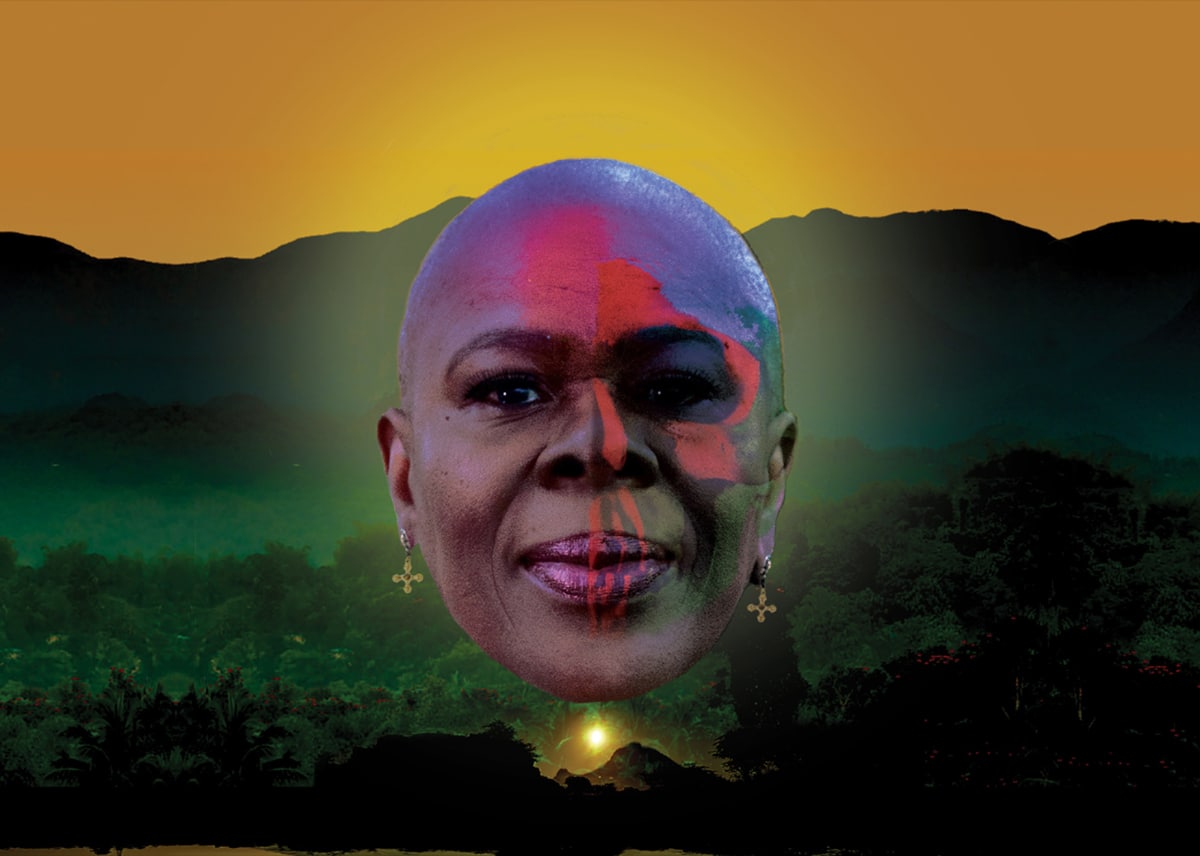

One of Park’s innovations in her adaptation is to deepen the emotional impact of The Harder They Come by enhancing the roles of the female characters, especially Ivan’s mother Daisy (Josie Benson), with a Cassandra-like intensity of fearful prophecy and Elsa, Ivan’s eventual girlfriend. Madeline Charlemagne moves easily on stage with an elegance matched by a supple singing voice.

Another of Park’s innovations is to take songs written for a solo voice, such as Jimmy Cliff’s tender ‘Rebel in Me’, and to enhance their power as duets (in this case a love song for Ivan and Elsa). More conventional but equally powerful are those moments where Parks takes lines from the lyrics of songs as succinct motifs to drive home a turning point. When Ivan rejects Hilton’s derisory offer for his splendid song, the vexed producer scolds him rhythmically and incrementally in song, predicting a mountain of trouble ahead, invoking Toots and the Maytal’s ‘Pressure Drop’ as an damning nail driven into the coffin lid of Ivan’s future, ‘pressure drop, a drop on you!’

The musical mostly sticks close to the original tone of the film. There is, though, noticeably more humour in the musical. Decades ago, I recall wincing during a scene in the film in which Ivan mercilessly slashes the face of a rival with a flick knife, all the while taunting, ‘Don’t fuck with me!’ In the stage musical, by contrast, the antihero is the repository for audience affection no matter his outrages. Throughout, a high level of jeopardy is maintained, in keeping with Ivan’s changeable mood and vacillations over which direction he will eventually settle on. Ultimately though, Ivan is emblematic of the dangerous, lone gunman and the uncontrollable rudeboy rebel Ivanhoe ‘Rhygin’ Martin who foreshadowed the violence to come in Jamaican society. ‘Everyone’s a Rhygin now,’ said Rhone when I spoke to him in 2002. ‘The levers of social control are missing.’

The Harder They Come is social history in musical form, illuminating the end of innocence and the beginnings of a febrile period in Jamaica which would culminate in a near civil-war, when as Toots and the Maytals warned his compatriots, not just the Rhygin-like rudeboys but everyone, ‘Oh yeah the pressure drop, a drop on you’.

The story builds towards an unstoppable calamity, what Jamaicans call an ‘autoclaps’. The clue to its inevitability is in the lyric ‘The harder they fall, one and all’, the counterpoint to the show’s title and main song. Living on the mean streets of Kingston carried real jeopardy in the 1970s, as it still does today. But the pervasive and defiant spirit of its inhabitants shines through figures like Ivan who calculates, ‘I’d rather be a free man in my grave/ Than living as a puppet or a slave’.

Watching this inspiring musical, which received a rapturous reception from an audience who started to join in with the cast on some of the songs, I was reminded of the late Trevor Rhone’s description of the ecstatic Jamaican filmgoers in 1972. There was a full house the night I went to the musical. Perhaps by the end of the run there’ll be three people per seat.

This review was first published on 3 October, 2025 in the TLS

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

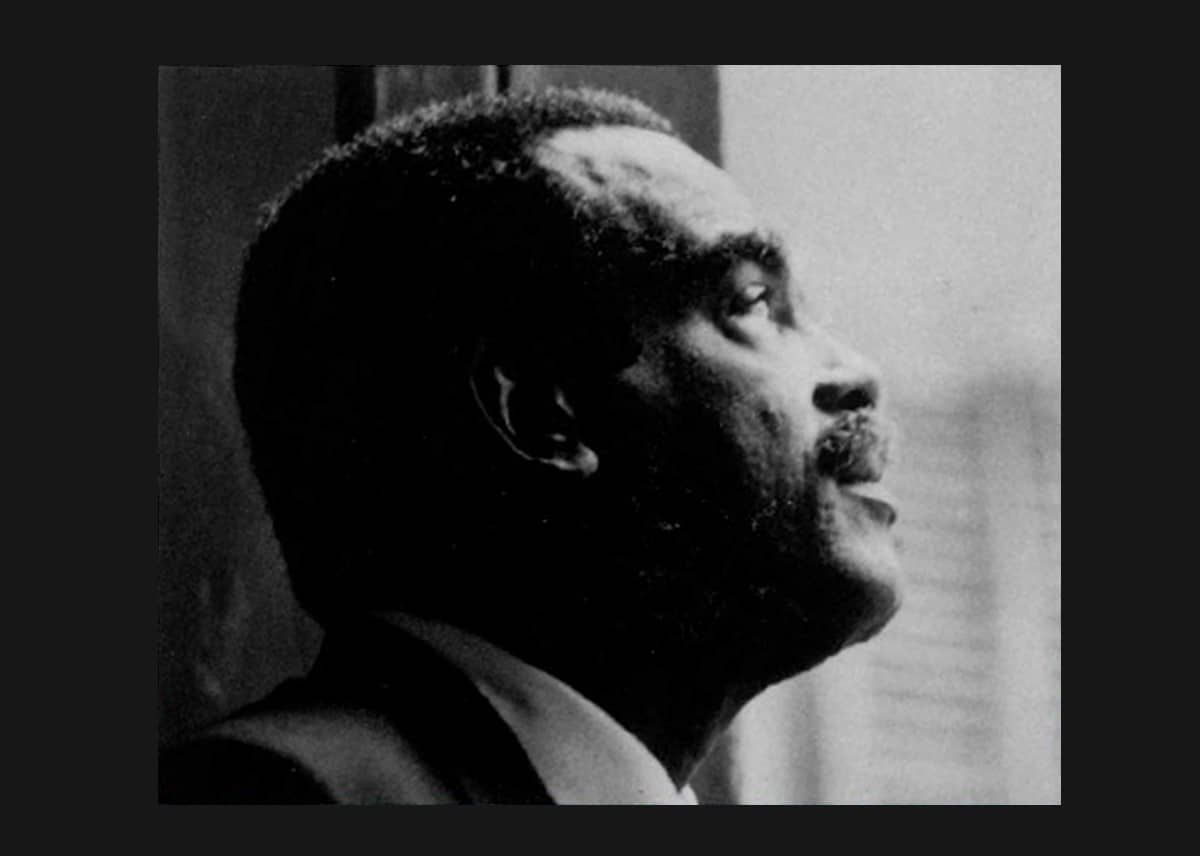

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps