The Message

Ta-Nehisi Coates

(Hamish Hamilton, 2024)

Review by Onyekachi Wambu

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Message is a meditative and now controversial work about the intersections between writing, narrative and belonging. Written as an assignment for the students in his creative writing class at Howard University, it takes on the form of a modern-day epistle – part memoir, part philosophical reflection, part literary provocation.

Coates, often seen as the intellectual heir to James Baldwin, inherits the clarity of Baldwin’s essays on race, identity, and the American condition. He opens the book with a Baldwin epigraph: ‘Though we do not wholly believe it yet, the interior dreams of people have a tangible effect on the world’ – a line that neatly sums up the book’s ambitions and underlying theme.

The Message thus departs from mere commentary, offering a restless exploration of identity, suffering, exceptionalism, and the stories we tell to survive history.

Coates opens by boldly contemplating the vocation of the writer. He considers the narratives that individuals and communities construct to make sense of adversity, and how these narratives, over time, solidify into ideological and spiritual ‘blocks of meaning’ that govern engagement with others and with the world. These narrative architectures shift according to collective and personal needs, and in their collision with the world, frequently consume and undo us.

In the subsequent chapters, Coates undertakes a journey across three geographies, each representing distinct notions of homelands of the heart and the head. There is an ancestral journey to the pre-slavery Atlantic homeland in Dakar, Senegal, to the Southern American slavery homeland, and then to Israel, the homeland of the imagination, whose narratives of emancipation from Egypt and Christian virtues of forbearance and forgiveness enabled the enslaved to not only endure but to adopt a model of emancipation that leaned heavily on delayed gratification in a paradisiacal afterlife.

Each stop along this tri-continental journey offers surprises. In Dakar, Senegal, Coates encounters a complicated welcome. Ironically, he appears to be the only person in Africa with a Kemetic/Nubian name – one shaped as much by diasporic black nationalist discourses of the imagination as by African lineage. Coates exhales, relieved from the weight of the American racial gaze, momentarily losing himself in a society where the beauty standard privileges those with darker skin tones. Yet he is soon reminded that he remains unmistakably marked as an outsider – an ‘American’ (‘white?’) foreigner in the eyes of the locals.

Making the requisite pilgrimage to Gorée Island, and the symbolic ‘Door of No Return’, he acknowledges the exaggerations in the narrative constructed for diasporic visitors – registering that the door’s symbolism sometimes overshadows the numbers and historical precision – but is nonetheless moved to tears by the experience. Here, narrative and need converge: the hunger for reconnection, for an origin story, creates a truth deeper than fact. Still, this segment of the book is brief, unrealised. There is no detailed excavation, as in the Israeli section. Coates admits to still processing what Africa means to him – how it functions in his psyche – not as a return, but perhaps as a question. As he noted in a post-publication interview, he recognises that he and Africans are kin, but wonders about the exact nature of that kinship.

He is on surer emotional and psychological footing in the next homeland – the American South, the 400-year crucible in which the African American was forged, with status and personhood hewn out and defined in a body of laws. It remains the contemporary theatre where the backlash against historical reckoning is being enacted. In Columbia, South Carolina – where Coates’ own books are among those banned under an early ‘Project 2025’-style censorship regime – he confronts surprising paradoxes. Supportive white conservatives, who disagree with his views, wrestle with the body of laws that mark them as Americans. They remain firm, almost religious, believers in the First Amendment of a constitution created in a slave state, one which aimed at equality and freedom. For them, the true measure of a civilised society lies in its capacity to entertain dissenting ideas, rather than erase them. The deeper struggle, however, is over history – who writes it, who owns it, and how memory, as Milan Kundera cautioned, can be preserved against the forces of forgetting.

The longest, most emotional, and politically fraught leg of the journey takes place in Israel and Palestine – visited by Coates before the cataclysm of October 7th, but since publication in its aftermath, the source of intense and sustained attacks. These often elide Coates’ description of Palestinian Jim Crow-like oppression with support for Hamas, despite the sensitivity with which he approaches the subject matter.

For African Americans, there has long been a powerful appropriation of the Jewish experience of bondage and deliverance. The Exodus story formed the bedrock of African American theological imagination and models of liberation. The Nazarene remains the model of endurance and redemptive suffering that guided generations of Black resistance, offering so many the possibility of Grace. Thus, Coates directly confronts the true spiritual and psychological homeland of the African American.

But the reality he finds in Israel is dissonant: emancipation and liberation from the Holocaust sit side by side with domination and apartheid; the latter embodying some of the tropes of his people’s own lived experience and humiliation, rather than their borrowed, imaginary, liberatory stratagem. Coates brings to this inquiry the weight of his own American experience, his community’s long relationship with the Jewish people, and the symbolic capital both groups have carried – via the projection of US power – in the global moral imagination.

In the aftermath of October 7, the moral terrain has become even more fraught. It is not lost on observers that many of the official American responses to the Gazan desolation were delivered by African American figures: The Vice President, the Presidential spokesperson, the Secretary of Defence, the UN Ambassador, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In the Gaza cataclysm, the face of the American empire appeared conspicuously Black. In subsequent post-publication interviews, this raises uncomfortable questions for Coates about complicity, power, and representation.

The search for homelands in Coates’ journeys of the heart and head is fine, but he could have reckoned more explicitly with the real-world home itself: the Empire and its now global supremacist ideology of manifest destiny. How African and Jewish Americans have both benefited from and suffered under its cold logic – and, at times, been absorbed into its machinery and its ability to create and project global narratives. What Baldwin might have dubbed ‘intangible dreams’ – which have real-world repercussions, whether in Hiroshima, Vietnam, Iraq or Gaza.

There is a deeper and larger contest at play: whose suffering is seen as paradigmatic? Who gets to speak for humanity? Who gets to moralise the world? The symbolic competition between Black and Jewish communities over whose pain is more emblematic, whose liberation more instructive, is not new. But Gaza may mark a turning point. One hopes it triggers a reassessment within both communities about their historical roles, alliances, and their capacities to speak from a place of moral authority in a changing world. A questioning of themselves as the default through which moral arguments about freedom and human suffering are understood.

https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/463295/the-message-by-coates-ta-nehisi/9780241724187

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

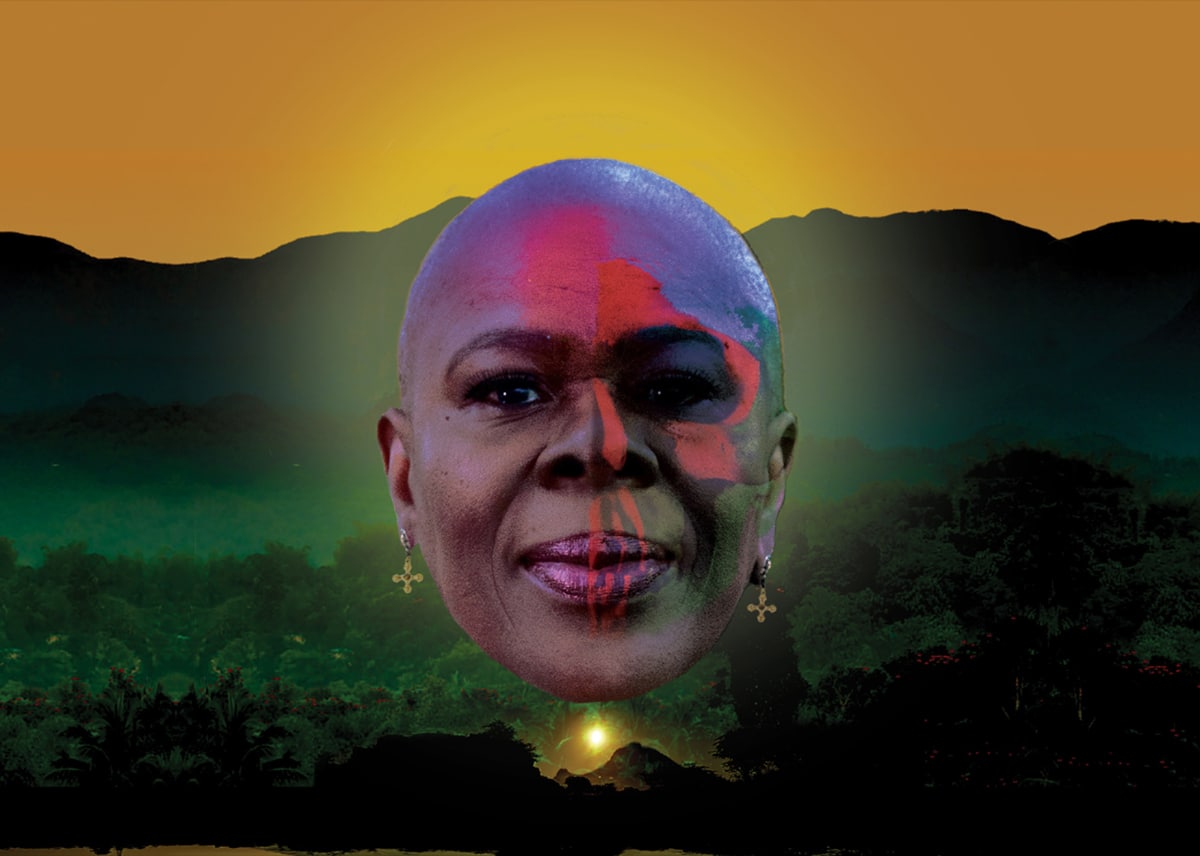

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

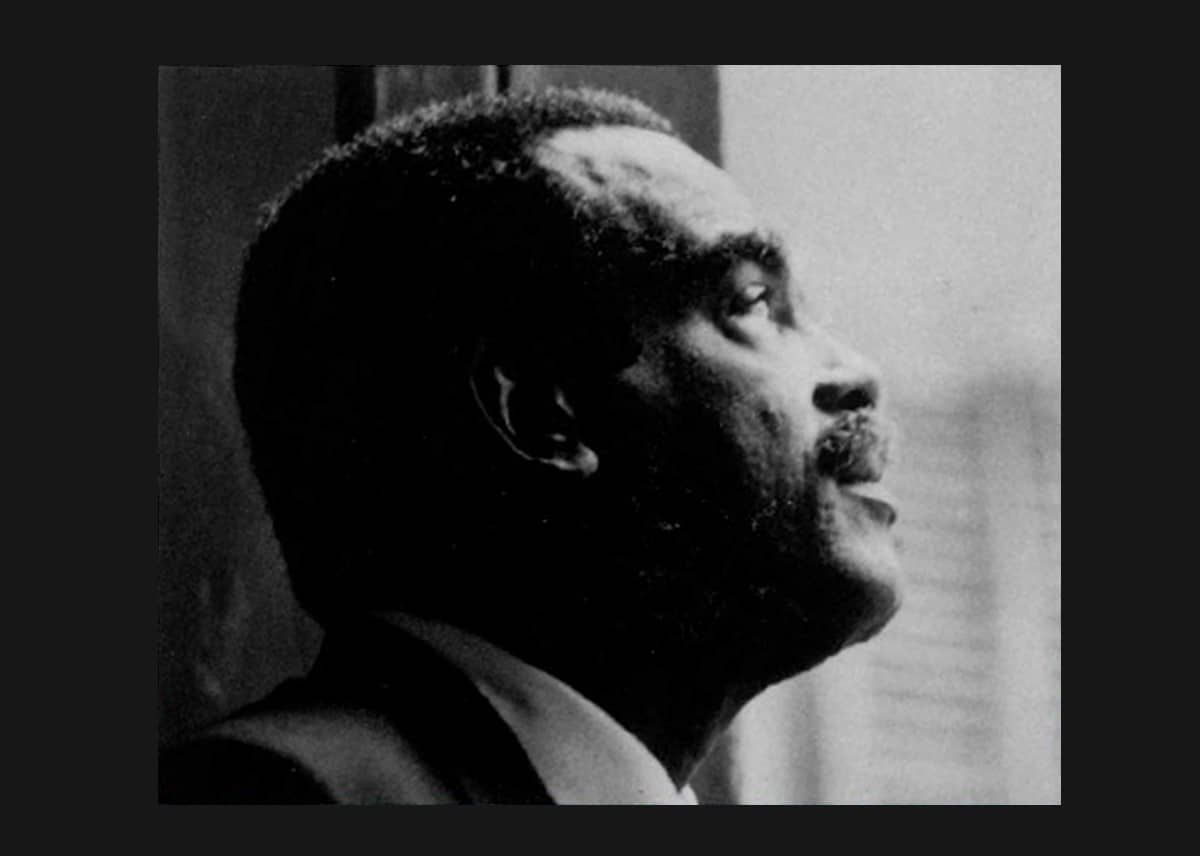

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps