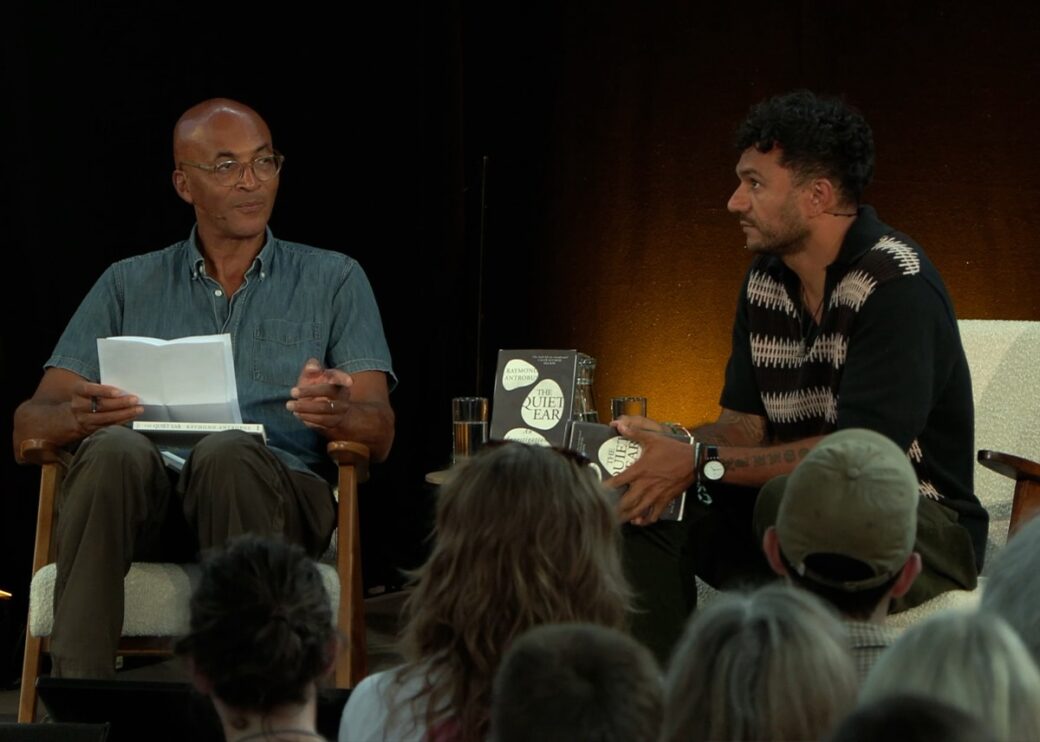

The Quiet Ear

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound

Raymond Antrobus

W&N, 2025

What is ‘missing sound’? Award-winning British-Jamaican poet Raymond Antrobus, whose work is taught in schools, suggests it could be ‘a misunderstanding, a mismanaged sense of self, a miseducation, a miscellaneous shelf in a mystery library.’ What joy when a poet writes prose: in The Quiet Ear – a book about what it is to be deaf in a world of hearing – we are given stories and ideas wrapped in the lyricism of poetry. Anger rarely reads so beautifully.

‘Being deaf doesn’t suit me,’ Antrobus wrote in his teenage journal, ‘Hearing aids don’t suit me.’ He recounts how they ‘highlighted my vulnerability and made me feel ugly, incapable and “disabled”’. Initially, he’d dismissed signing as a ‘hyperactive drama’. Instead, teen Raymond threw himself into sports, becoming a champion swimmer; the submerged world of water suited his quiet ear. Underwater, we are all deaf.

His mother, artist Rosemary Antrobus (‘a rebel, a smoker, a drinker, had sex unmarried’), signed him up to anger management sessions. His father, Seymour Birch, bought him a punchbag, on which the adolescent Raymond sprained his wrist. Seymour, all ‘easy-going “irie-vibe” Rastaman’ to the outside world, would himself use his family as a punchbag when blackout drunk; on awakening, he’d remember nothing. ‘Because his violence only occurred when he was drunk and behind closed doors, it signalled something to me about privatising rage, holding it in only for those closest to bear it,’ writes Antrobus.

There was respite. Aged ‘four or five’, as his parents’ relationship worsened, his grandmother took him and his sister to the ‘calm, cosy comfort’ of her Hertfordshire home: she ‘sugared our cereal in the morning, made pink mousse for dessert, boiled potatoes, roasted the chicken, microwaved the gravy; there were always biscuits.’

In his teens, it was swimming, football and Busta Rhymes that helped with the frustration of growing up a deaf kid in Dalston, and his fierce need for others to recognise his intelligence. That, and his mother’s unwavering advocacy, fighting for his access to deaf schools and decent teachers so that he could ‘form my own hybrid D/deaf identity.’ Nobody had realised he was deaf until he was seven, when his mother had clocked that he couldn’t hear the loud ringing of a landline. She’d swung into action.

Not all of his peers made it. Tyrone Givans, a ‘handsome black boy with blue hearing aids’, was a fellow student at the deaf school – talented, outgoing, ‘running across the football pitch, the tick of his Nike trainers glowing as if affirming him’. After the supportive structure of school, however, ‘things slowly fell apart for him.’ Tyrone’s life ended when he hanged himself in custody: isolated, his hearing aids taken away. Antrobus suggests an unofficial cause of death as audism: the structural discrimination faced by deaf people. Yet there are fewer deaf schools and less support for deaf children now than in 2003, the year Antrobus left school: ‘It makes no sense.’

He began writing poetry aged six, a year before his deafness was officially confirmed. As an adult, Ted Hughes served as anti-inspiration – Antrobus was horrified when he read Hughes’ poem ‘Deaf School’, in which the former Poet Laureate described deaf children in animalistic terms: ‘small night lemurs caught in the flash light “alert”, “simple”, “lacked” a dimension’. Antrobus responded with poetry of his own – ironically winning the Ted Hughes Award for his first collection The Perseverance. He used the prize money to buy digital hearing aids. He’s a dad himself now, to a four-year-old boy (‘outdoorsy, observant, wide-eyed’) who is not deaf. He and his small son go on nature walks together, where he points out the birds – ‘hawk, crow, pigeon, swallow’ – who, without his hearing aids, would remain silent to him.

In The Quiet Ear, Antrobus explores the lives of other deaf artists, from Francisco Goya to Johnny Ray to a host of poets. But mostly it’s an examination of his own internalised ableism. Deaf shame and deaf anger were burned into him. Curiosity and investigation provided ‘balms for my old, heavy, unforgiving voice, countering some of my own ableist self-talk, nudging me out of judgement towards […] a world of sound and silence with a life of poetic potential.’ He made it, and we are all the richer for his gifts.

https://www.weidenfeldandnicolson.co.uk/titles/raymond-antrobus/the-quiet-ear/9781399619691/

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

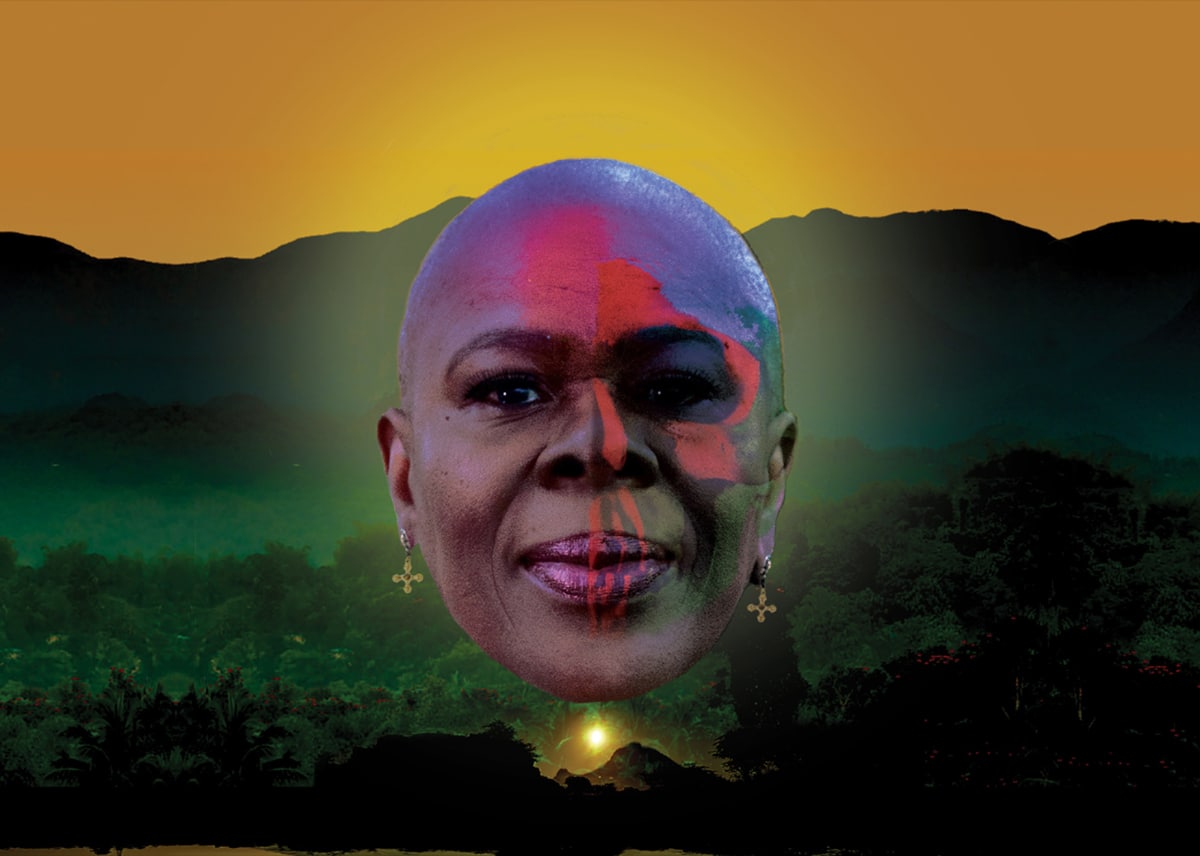

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

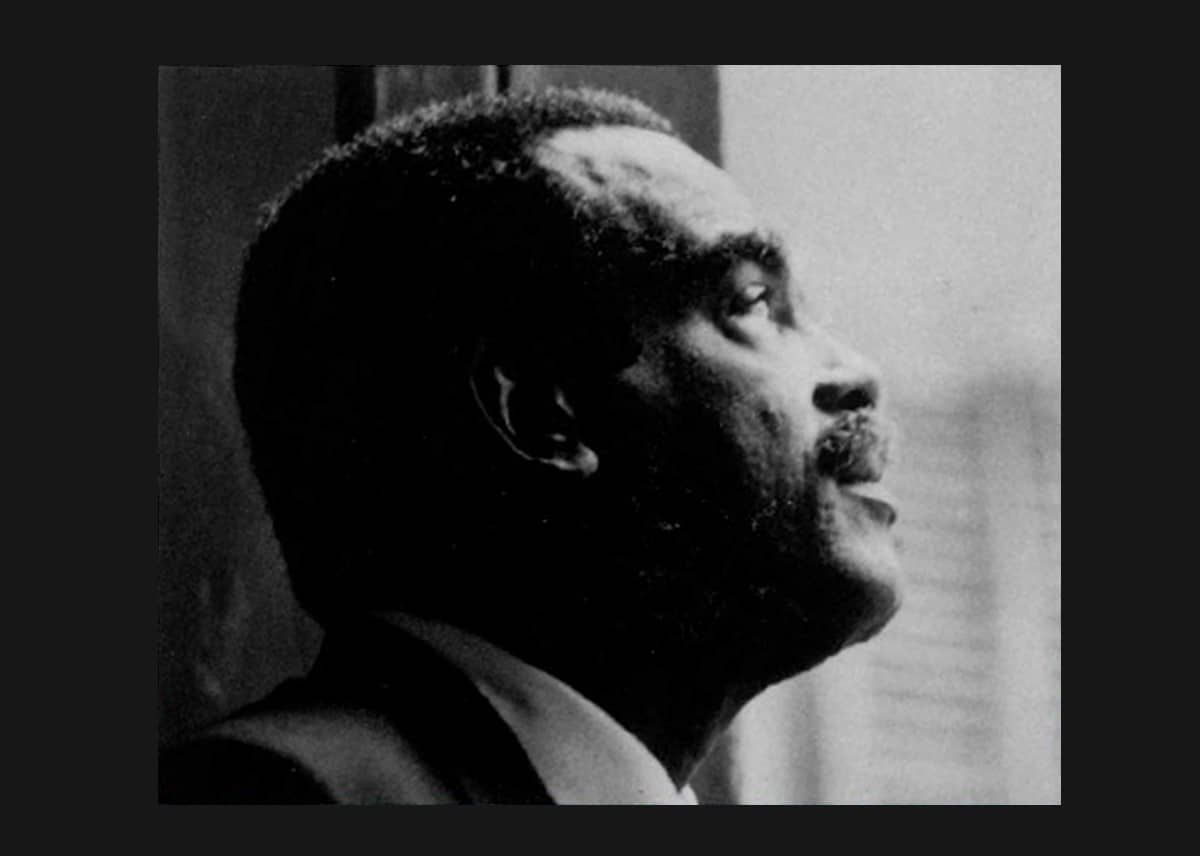

Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

Jimmy Cliff’s death last month prompted an outpouring of affection. In an augmented extract from I&I: The Natural Mystics, a social history of Jamaica, our Director reflects on Cliff’s emergence as a reggae pioneer.

Writing saved my life

'I just started writing down the words that I was feeling at that moment…To my surprise it felt really good. It was another form of release!'

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps