A flag as a broken mirror

John Siddique

The blue sky at the end of August is morning tender. It began on a public holiday. It’s not autumn, but you can’t help feeling the soon of it. It began on a public holiday, but surely it began a long time before. For even though the sky is always the sky, we live mostly in the stories we tell ourselves that, without the mirror of awareness form a broken set of reflections that always lead the same way. We are driving to the sea under the August blue sky, along Rossendale Road. We have left the valley and will turn soon past the crematorium, where my mother’s body became ashes – a blue-sky day too. We played Led Zeppelin for her, both on the day of the cremation and the day we gave her ashes to the earth. Our bodies are the nameless earth, but we name the earth in the stories we tell ourselves. We claim and draw borders in the stories of belonging we tell ourselves.

As if to prove the power of stories, we see three men, shirtless but with flags tied as cloaks. They have a pile of flags and zip-ties and a ladder. They are deeply engaged in their day of work, putting their stories up as flags along this road that leads around the edge of Burnley towards either the Forest of Bowland or the motorway and the western coast. On the other side of the road, two children, both around eleven years old, stand silent, holding a flag. My wife and I, in our black 4×4, under August blue sky on a road that always has a touch of death to it.

My wife looks at me. She has had to learn what these stories mean.

She says, ‘Remember what Toni Morrison says, love: the purposes of racism are always distraction. Are you okay?’

‘No.’

‘It’s terrible,’ she says, ‘but it will all blow up in their faces.’

‘I don’t want to write this story.’

Jimmy Baldwin leans forward from the back seat of the car. ‘John. You must not let your heart die; you have to find a way to stay intimate with life and make your art. They don’t believe in love.’

‘Jimmy, I am so sorry I brought you here to see. I wish you could rest in peace.’

‘I am in peace. It’s you who have to live now and bear witness.’

‘I don’t want to write this story’, I say. ‘I don’t wish to enter their narrative. It took me years to see that even responding to colonialism is to allow their fascism to be centred in my life and my work. I have a set of stories about allowing delight and about making a world that is real enough to contain that and my body,’ I tell him. ‘But I can’t write it here. It feels like a lie to write it here; no publisher, broadcaster, or readership is interested in the joy and spirit of a man like me, we’re only meant to be exotic or bleed for them. So many writers of colour give in to this. It feels like there are hands around my throat, and hope won’t do.’

Jimmy winds down the window and lights his cigarette. He’s wearing a lovely blue shirt and a light scarf. ‘I had to leave America in order to write and to live. It doesn’t matter how many times you explain that all this is a threat against life – my life, your life – they feed on that and do it all the more, but tell you that you are wrong, that it’s not what your experience shows you every damn day, that it is just their pride in their country. They have always shown us who they are through their actions.’

‘I don’t believe in white people, or brown people, black people, or borders,’ I say. ‘But I have to, because they do. It’s not natural to my soul, but I live in this body, and I exist so that must be a good thing.’

‘Yes,’ he says, ‘exactly so.’

‘But where can we go? You went to Paris, to Istanbul. Was it any better?’

‘Yes and no, but they gave me something – myself. There my body was not under the same threat of suicide or death. I still got somewhat lost. You have to do better than me.’

I tell Jimmy of the times I was hunted and beaten by Nazi skinheads in my teens and the coils of that still in my nervous system.

The two boys with the flag – the grandchildren of those skinheads, perhaps?

‘I know of the endless denial of our lives,’ he says. ‘But you know my secret.’

‘I do,’ I say. ‘But say it for us. I’d love to hear you say it.’

My wife and I breathe together. We’ve talked about him so many times, but here is one of the patron saints of our bookshelves.

‘No,’ he says, ‘I’m books on your shelf, a voice of literary family you carry with you. It is your time, John. You need to let me hear you say it.’

His eyes smile in my rear-view mirror.

‘I believe in knowing and living authentically from my soul, I believe in literature and making art from what is in front of me,’ I say. ‘And if they are going to give us this distorted history, their unending colonialism, the lies of who belongs, a broken mirror of a flag, vassal politics, the piercing dirty looks on streets and in coffee shops, billionaires and media attempting to usher in ethno-nationalism through fascism and genocide for profit, the complicit silence of so many colleagues and friends, and these false borders – then they are all mine. You’re giving them to me, so they are not yours anymore. They are mine now under this blue sky, and I can do anything I want with them.’

Other Wild

Emily Zobel Marshall invites us to heal by connecting to our senses and the natural world

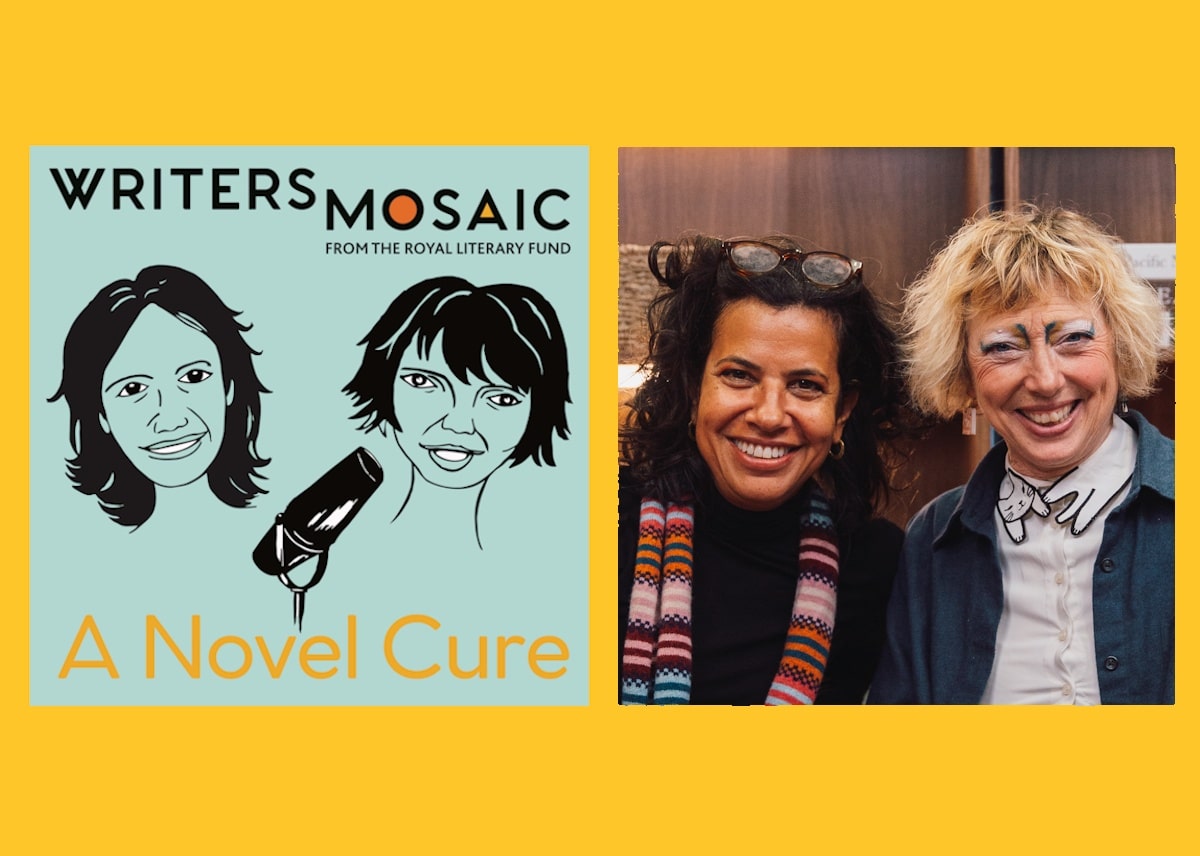

Fiction Prescriptions

Co-hosts Ella Berthoud and Isabelle Dupuy introduce our new podcast series, Fiction Prescriptions: A Novel Cure, focussed on bibliotherapy. Each month listeners can write in with their dilemmas, and our dynamic duo will suggest remedies for the head and heart, drawn from books.

All the men my mother never married

A chapter from an unpublished autobiography, dedicated to my mother, Sarah Efeti Kange

Granta 173: India

A look at four short pieces of fiction from Granta's latest edition showcasing Indian writing

The Thing with Feathers

Dylan Southern’s film adaptation puts masculinity front and centre

It Was Just an Accident

Iranian director Jafar Panahi's film probes the relationship between individuals, the state and violence with determined humanism

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Afro-Caribbean writer Frantz Fanon, his work as a psychiatrist and commitment to independence movements.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube