Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The British novelist Derek Owusu once revealed that it took him five years to read Paul Gilroy’s There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack and now I understand why. Texts by the likes of Gilroy and Édouard Glissant, whose Poetics of Relation took me a frantic four months, can be intense and stifling reads, but you cannot cut corners or rush the route to self-knowledge. The many concepts and ideas delineated by Glissant in Poetics of Relation are too rich and complex to be covered meaningfully here. The book exists as a journey.

Poetics of Relation interrogates the very language(s) it was written in. Critical texts in French famously translate into English clumsily, and Glissant’s writing combines French with Creole idioms and Antillean folk imagery in search of a way of seeing and being seen in the world that is inherently Antillean. Not that I’m criticising the translator, Betsy Wing. I have not read, and am unable to read, the book in its original form. In her introduction, she tells us that our probable experience of being constantly challenged in our attempts to read and understand was precisely Glissant’s intention. Those of us who are used to reading prose fluently are constantly interrupted, as if by the line breaks, word, and punctuation choices of a poem that constantly ask us why they’re there.

Glissant’s career is perhaps most notable for the concept outlined in this book apropos the right of individuals and groups to ‘opacity’, and the presentation of this book certainly lives up to that notion. Neither French, an imposed colonial language, nor Creole, the stagnant language of the everyday, could alone achieve a sense of self for Antilleans. Glissant had no intention of rejecting French, as the late, great Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o rejected English, but purported to interrogate the imposed colonial language from within. He wished to break received relations in standard French down, to create new relations and meanings that are subjectively Antillean, exploding a marginalised people into a globality contrary to Charles De Gaulle’s description of the islands as ‘dust specks on the sea’. Our thoughts are colonised by virtue of their language being that of the coloniser, and so we must continually destabilise these ‘linear sequences’ in order to arrive at a poetics of relation, which in itself presents translation challenges because Glissant creates new phrases, often ‘noun-phrases’, in French. Glissant fully intends to stop readers in their tracks so that they will engage in the process of interrogation actively, but I was left feeling mocked when, towards the end of the book, he uses the phrase ‘We, as Caribbean people’. My identity as a member of the Caribbean diaspora does not help me to better understand his ideas, although I could write a book about how much my brain wanted to fight off the reading experience.

From his teasing of a definition of ‘opacity’, spread through the book, I understand the term to stand for the right of marginalised people to not be understood by the rooted economic majority. Official languages are a means of control and of imposing criteria upon which identity and belonging are judged, though identity should exist as no less deserving outside this. Multicultural London English, though now perhaps an inadequate term, is a modern example of how standard English is interrogated from within, and only accessible to those who normalise multiculturalism. Jamaican patois, of the many in the Caribbean, is an older example of a language rooted in imposition that was made opaque to the oppressor by means of its absorption of indigenous and African words, terms, elisions and transmogrifications. Glissant questions the very idea of rootedness, defining it as ‘unique, a stock taking all upon itself and killing all around it’, and adopting instead Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s idea of the rhizome, an ‘enmeshed root system, a network spreading either in the ground or in the air, with no predatory rootstock taking over permanently’, maintaining the idea of rootedness but challenging that of one single ‘totalitarian root’. This thought is the principle behind Glissant’s poetics of relation, in which ‘each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other’. This is in light of our current politics in Britain, the US and other countries, where the far right is hell-bent on returning to, or reifying, a monocultural and/or monotheistic rootedness.

‘Sometimes, by taking up the problems of the Other, it is possible to find oneself,’ Glissant tells us. ‘Contemporary history provides several striking examples of this, among them Frantz Fanon, whose path led from Martinique to Algeria.’ This is an example of rhizomatic errantry which, in Fanon’s case, was a journey from the Other to the Centre, and on somewhere else, in order to further develop his identity. As a Martinican, and therefore a citizen of a department of France which had no interest in independence, it took his migration to Algeria, a state locked in a bloody war of independence, to fertilise his thoughts on postcolonial nationalism. So often we are caught up in our own nationalist politics that we fail to acknowledge others, or see where we might have common goals, or how our sense of place in the world might be expanded. This can account, for instance, for the existence of Ukrainian Zionists one might have assumed to be in solidarity with Palestinians.

My reasons to live in the UK are not the same as that of my migrant grandparents, who journeyed from the Other to the Centre and stayed there, raising their children and grandchildren to become good servants to Christian capitalism. We are taught that Britain is the safest place for us to be; that we have been raised with the privilege of being British citizens; that our passports give us more freedom; that our language is the most important. James Baldwin had to leave America in order to understand himself as an American and, further, to critique his country out of love. If there’s one thing I’ll take from Glissant’s book – and there’ll be more realisations along the journey – it is to consider where my rhizomatic errantry might take me next.

On not becoming an army officer

'To this day, every time someone tells me they are an officer in the army, I first look at their knees.'

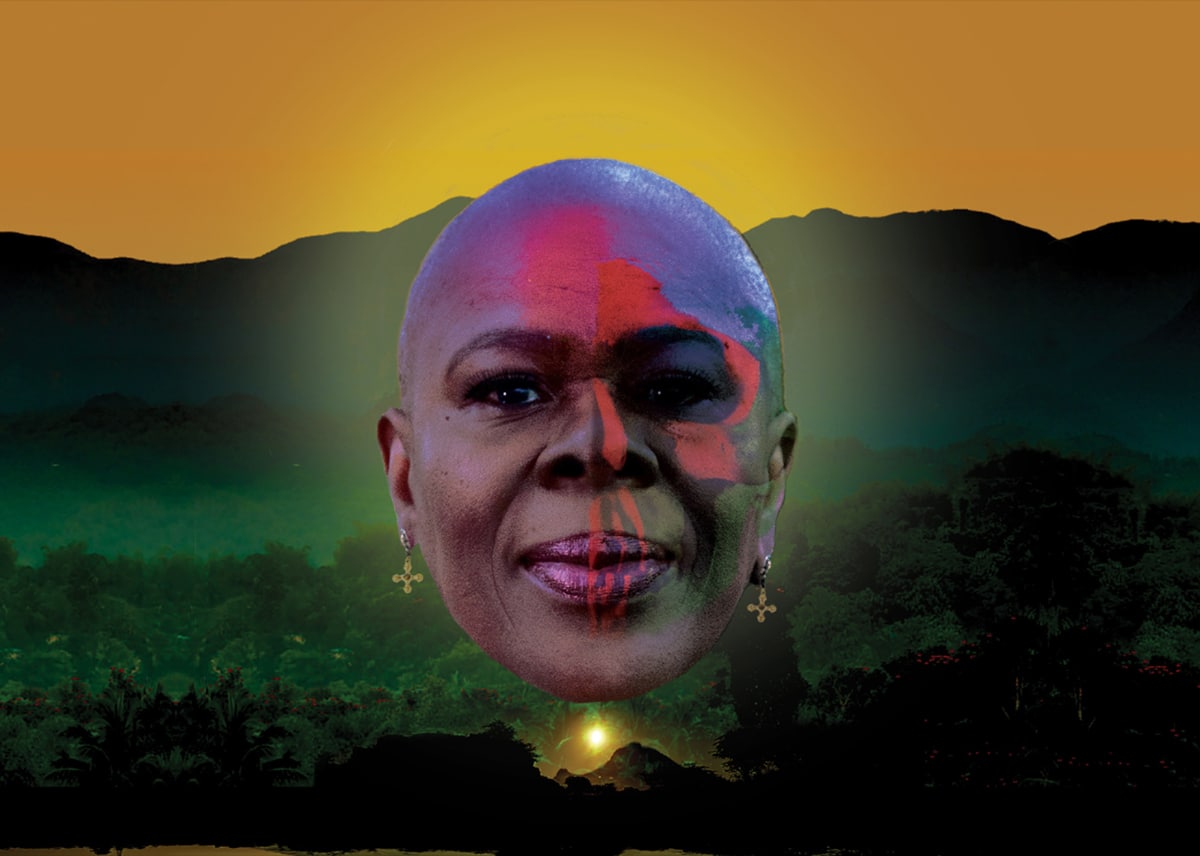

Yvonne Brewster remembered

Remembering the life and legacy of the pioneering Jamaican theatre director and actress Yvonne Brewster

Jodhpurs, Tweeds and Monocles

Inheriting the patterns of life marked into second-hand clothing

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny

The Booker Prize 2025 shortlisted novel is a beautiful exploration of love and loneliness between two young people

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps