Jimmy Cliff’s influence on the soul of reggae

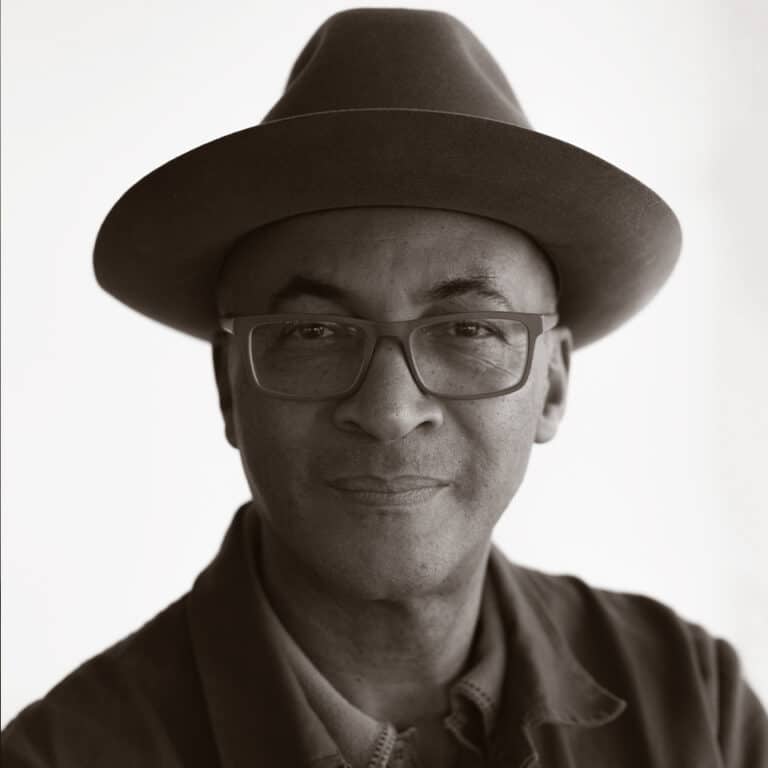

One night in the early 1960s, Jimmy Cliff walked through the door at Beverly’s, a restaurant and ice-cream parlour that Leslie Kong ran with his brothers in Kingston, Jamaica. Cliff made an unusual proposition. Had they ever considered branching out into Jamaica’s exciting new recording industry? Before the Kongs could throw out the teenage prankster, Cliff broke into song. He had composed a kind of musical love-letter to Beverly’s, which he was convinced they could use as a sure-fire entrée into the recording business. ‘I sang the song ‘Dearest Beverly’. The two other Chinese brothers, they laughed,’ recalled Cliff, ‘but the other one [Leslie], he said, “Oh, I think he has the best voice I’ve heard in Jamaica.”’

Cliff quickly built up an impressive following with a string of uplifting and spiritual Ska songs, including ‘Wonderful World, Beautiful People’, which were underpinned by socially-conscious lyrics. By the start of the 1970s, his career was about to shoot off into the stratosphere. Cliff had been lined up to star in a small, locally-made music and gangster film, The Harder They Come (1972). The film, which substituted the original 1940s rude boy, Ivanhoe ‘Rhygin’ Martin, for a 1970s wannabe reggae star up from country, who turns bad, as ‘bad as sore’ as Jamaicans say, broadcast a raft of songs which would become the soundtrack to the 1970s, not just in Jamaica but in many countries around the globe. At its centre was a portrayal of the extraordinarily vibrant world of reggae with scenes and attitudes that perfectly mirrored the reality. It offered up fantastic opportunities for Cliff and a scattering of other singers. Later, the director, Perry Henzell, would explain that he’d never considered singers like Bob Marley for the lead role because ‘Bob Marley had not really surfaced at that point […] not for me anyway. Jimmy [Cliff] was much bigger […] at this time in terms of selling records and all of that.’

Thirty years on from the film’s screening, Trevor Rhone, the co-author of the screenplay, enthused over the bold, imaginative leap that he and Perry Henzell, assisted by Cliff, had taken in ensuring that the film captured the language of the streets. Just how bold can be judged by the distributors who, nervous about the thickness of the patois, took the precaution of adding subtitles to the film.

Rhone was an elegant seventy-something when I interviewed him, a man whose laconic manner disappeared as his memories dropped through the layers of the past, like one trapdoor after another. His rich, stage-crafted voice was a perfect pitch for his enthusiasm. ‘The first thing you, young man, should know is that Jamaica was never the same after the screening. And the music! Toots, Jimmy, mostly Jimmy,’ Rhone cooed, ‘the music was an instrument of repair.’

Newcomers to reggae who stumbled across the film were struck by the raw and powerful sound that was ‘as bone-marrow irresistible as the blues’. Critics lined up and genuflected. They were amazed by the depth of the music and by the dramatic background which the movie revealed.

Cliff was at the helm of music ‘more earthy and real than Johnny Nash’s’, according to Phonograph Record. ‘Believe me,’ wrote its critic, ‘you’ll wonder how you managed to live so long without it.’ The journalists were mostly saying the same thing: ‘You’ve been happy enough with the sizzle, but, with Jimmy Cliff, here is the meat.’

But after the release of The Harder They Come, the film’s star began to feel ambivalent about his association with the problematic image of the badass black man who would cut you if you crossed him.

Perry Henzell recalled the enigma of Cliff: ‘Right after the movie [Jimmy] got into a black Muslim thing.’ In fact, on the album that he released after The Harder They Come, ‘he was wearing a suit and tie and carrying a briefcase, and he had sort of close-cropped hair.’

Jimmy Cliff was never really a close fit for Ivanhoe ‘Rhygin’ Martin. In his own life, with his searching and soothing voice which spoke to a long overdue, ‘better must come’ future for the descendants of the enslaved, Cliff was always more choirboy than rude boy.

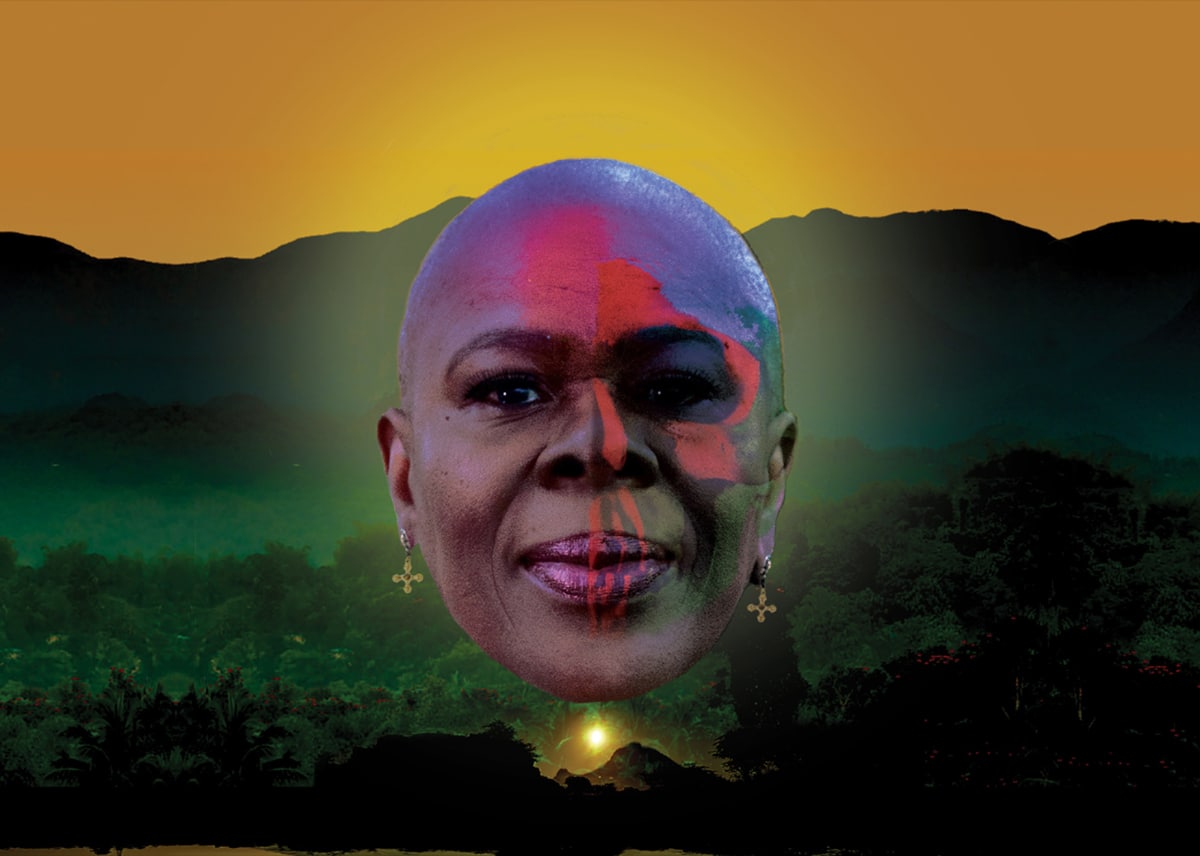

Yvonne Brewster remembered

Remembering the life and legacy of the pioneering Jamaican theatre director and actress Yvonne Brewster

Writing saved my life

'This new writing thing became part of my self-harming ritual. After I would cut, I would write...'

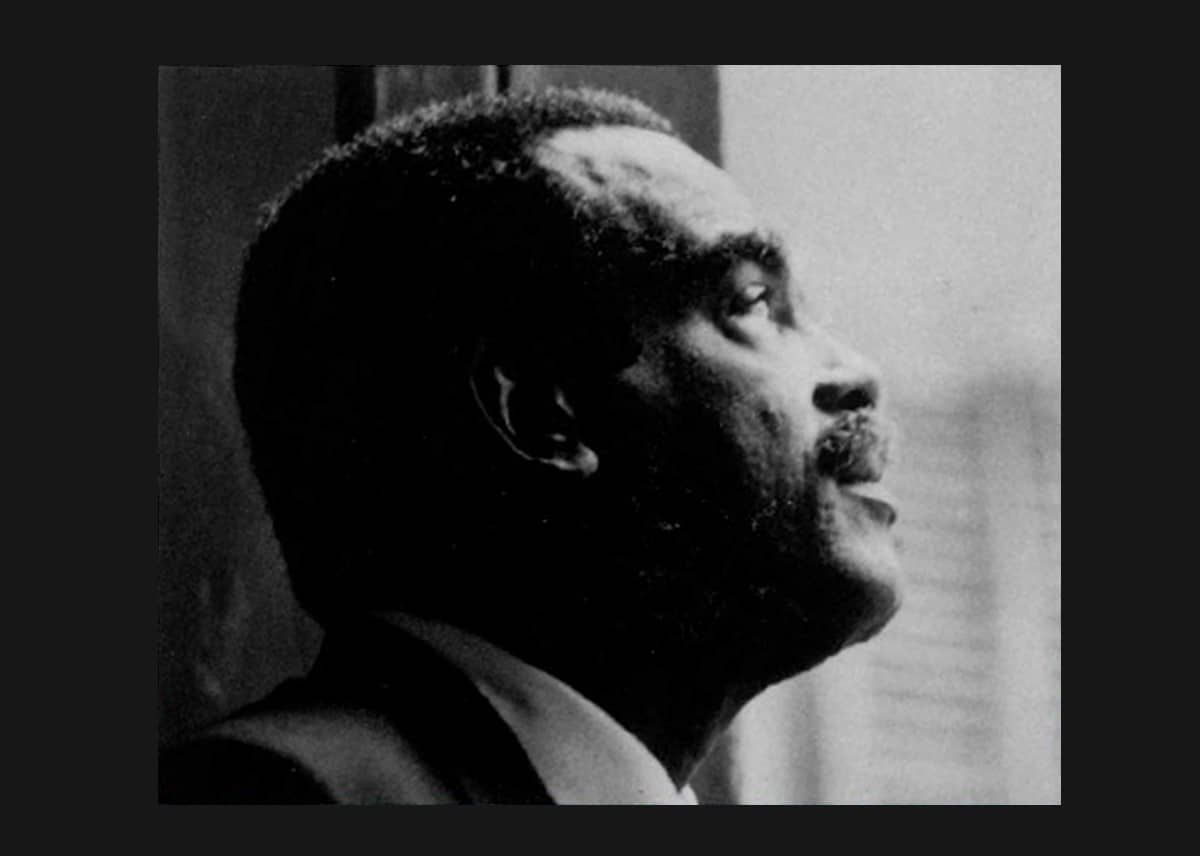

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Ever Since We Small

Celeste Mohammed's novel explores both the far-reaching impacts of colonialism and the small realities of life that binds its characters

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps