Made to love magic

Anjali Joseph

The Magician in the tarot interests me. The Rider-Waite deck, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith and first published in 1909, shows him in a red and white robe, an infinity sign above his head, and on a table in front of him a cup, a sword, a staff, and a pentacle – representing the suits of the tarot. He holds a wand. I associate this depiction with Mandrake the Magician, hero of the comic strip first published in the 1930s and reprinted in one of the daily newspapers in Bombay when I was a child. Mandrake is a suave, top-hat-and-tails stage magician; but he possesses all sorts of other powers, whether lightning-fast hypnosis that allows him to befuddle villains, or the ability to transform his physical body at will, or to levitate or instantly teleport himself.

In the much older Tarot de Marseille, the Magician is Le Bateleur (or, in the Italian tarocchi, Il Bagotto), a picaresque character dressed as a jester, standing in front of a table bearing cups, balls, and other paraphernalia of the streetside entertainer. He looks like an escamoteur, one of the sleight of-hand artists who operate outside Paris metro stations, asking passers by to bet on which of three cups covers a ball or a coin. In this deck, both the Magician and the Fool function, when tarot is played as a card game, as trumps.

To me, however, in the Rider-Waite deck, the Magician (whose caption might be ‘I do!’) is an obverse for the Hanged Man, a beguiling figure suspended from a gibbet of sorts, upside down, by one ankle. He has a halo and an air of renunciation. Sometimes I think of him as holding a yoga inversion: giving up on the usual ways of the world in favour of hanging like a bat, observing. His caption might be ‘Nothing doing’.

I like the tension between the two ideas of the Magician, or magic in general – doing magic (acting on the phenomenal world, making things happen, creating incontrovertible proof), and pretending, or creating an illusion.

In the present historical moment, among the educated and adult, it can seem as though almost anything is acceptable as an attitude, except credulity. I don’t think that those under the age of thirty see the world that way, but the generations born in the 1960s till, perhaps, the 1990s are steeped in a slightly self-denying adherence to science over religion, or as a religion, that may stretch all the way back to the Enlightenment. Coupled with that, I feel, is grief at the sense of wonder that was lost or that we were forced to leave behind in childhood. One of the gifts of the enormous success of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series has been that for the generations of children who grew up reading or having those books read to them, and watching the films, magic continued to exist as perfectly respectable; they were never expected to put it away and become sceptical, as befits a grown up.

Growing up, and growing older, I lived in my imagination, but also had a yearning towards the spiritual, religious, or magical. Unusually for an Indian family, there was no religious ritual when I was a child, neither among the Hindu relatives on my mother’s side in Bombay, nor from my father, who had been brought up Syrian Christian but flatly refused to take me, an experimental four-year-old, to church even when I wanted to see what it was like.

My forays into the unseen were self-directed, and idiosyncratic. Among them: aged about four, I tried doing my own religious rituals with some sea shells and a small bottle of rather strong eau de cologne that my mother had given me (Babe, by Fabergé, since you ask); at eight or so, by now living in Warwickshire, and having heard something on the radio about the Donovan song ‘Mellow Yellow’, I had a go at drying out a banana skin in my room, then lighting the end of it and inhaling the smoke. No transcendence resulted. Around the same time, I borrowed one of my mother’s yoga books, by Swami Sivananda, and read about postures, concentration practice and meditation, and tried to set my clock radio alarm for 4am to leave myself time to practice all the things necessary to arrive at enlightenment. I was attracted by the siddhis, or powers, that reportedly occur along the way, and which the spiritual aspirant is warned not to be distracted by – among them, if I recollect, the ability to read others’ thoughts, to teleport, to become infinitely small or big, to levitate, and so on.

The alarm went off at four a few days in a row, but I didn’t manage to do much more than hit snooze before dragging myself up later and slugging to school. However, I did glean from the book that it was important to be able to sit in the lotus pose – and so spent hours practicing that while reading (probably books about children who erred into magical worlds, like Alan Garner’s The Owl Service). Some of the other elements of that time reappeared years later: I did yoga teacher training through an institution named after Swami Sivananda and founded by one of his students; more unexpectedly, I was teaching a creative writing course in Devon a few years ago at which Donovan was among the cohort. Did I ask him if he’d ever successfully smoked dried banana skin? Strangely, I don’t remember.

When I was younger, I always felt embarrassed by the two strongest pulls in my life: one, towards magic (or the spiritual), and the other, towards art. They seemed inimical to each other: spiritual people, surely, didn’t mess about making up stuff; real artists presumably didn’t want to transcend so much as practice their vocations. I would have to get rid of one of them.

For the first decade or so of my adult life, both these vocations – to magic, and to art – were something I concealed. And yet, the righteous world of jobs and rent, getting ahead, being practical, et cetera, felt thin and unsatisfying. When I moved back to Bombay, in my mid-twenties, and began working as a journalist on a daily newspaper, I continued to read the ‘books you buy on the pavement’, a phrase a friend of my parents used for her collection of pirated copies of popular esoteric literature like Creative Visualisation by Shakti Gawain, or The Silva Mind Control Method by José Silva. Most of them expounded a variant of the thesis: imagine it and it’ll come true. It never quite did, or not in the way the books suggested, but what was interesting was the way that patterns of events repeated themselves, something to which I began to be attentive. In the first book I wrote, Saraswati Park, the son of a failed writer begins to write, himself, in his fifties, after coming upon a volume of Mark Twain essays including ‘How to Tell a Story’ at a pavement bookstall in Bombay. In my second novel, Another Country, I felt that beneath the story of the inward loves and life of the main character, Leela, was an underlying dialogue: between Leela and her witnessing soul, if you like, and that much of the affect of the book wasn’t from the external ups and downs of events she experienced and caused, but instead from a sense of grief for a lost childhood experience of connection.

Connection to what? To the world – to wonder. When I was moving from Norwich to Assam in 2014, there were a few days in between my packing up some possessions, giving away the rest, and clearing my rented flat of everything that I’d brought into it in the previous three years. I’d packed my coffee pot, and so went early each morning to a nearby coffee shop. The final day, the day I would leave for the airport, there was a small family sharing my table. The parents were talking to the barista, and the child, a boy of about six or seven, amused himself playing with ice cubes from his glass of water, sliding them around, watching how they moved. To him, matter was interesting, animated, even playful. He may have felt a recognition of that in my gaze, because he looked up and we shared a smile. Then we both returned to pretending to be sentient humans in an inert world. He put the ice cubes back in the glass and left with his parents, and I went back to my flat, got my suitcase, and went to the airport.

During my time in Assam I became fascinated with whatever I could learn about tantra (sometimes from conversations, but mostly from books). It is a philosophy that has had huge impact in the eastern parts of India, where goddess worship has been important throughout history. I also happened to study yoga in the Himalayas, but what we learned there was Vedanta, the philosophy expounded at the end of the Vedas in the Upanishads – from which, among others, T S Eliot borrowed in the Four Quartets. Vedanta doesn’t have much patience for the phenomenal world of experience; the ideal is to grasp that the phenomenal is unreal, then focus on ‘source’. Tantra has a different emphasis: it seems to suggest that the correct relation to the phenomenal world, or to being embodied, is one of play. Look at how the ice cubes move!

Many of the principles I extrapolated from what I read of tantra found their way into Keeping in Touch, my fourth novel, in which an Assamese woman and a British Asian man begin a long-distance relationship of sorts, with, in the background, an exceptionally long-life lightbulb that may, or may not, have magical properties. For example, the idea that, as Keteki, one of the protagonists, thinks while in a friend’s car, ‘Everything is alive’ – even a class of being (like objects) usually thought of as inert. Or, the sense that how time works may be very different to what the usual chronologies imply – perhaps many different worlds and even incarnations are all happening simultaneously rather than succeeding each other, coupled with an awareness of how attention focused on something or someone can alter its size (make it infinitely big, or infinitely tiny) or even change its duration.

In the end, the figure of the Magician is also tied into the sad image of an inanimate world through which conscious humans move, acting or being acted upon. This, too, is misleading. The more modest figure of the Bateleur – the illusionist who knows that in attention and perception lie gateways to reality – offers more lightness (levitation, of a sort), and a first step into a different world. This is not a world where cause and effect are rigidly correlated, but a mode of being and becoming that offers more potential for surprise, the more unpredictable rhythm of things that grow. It’s the world of nature, the world of fiction, and also the world of magic.

In Olney River

A poem by Roger Robinson about the feeling of being watched by white families as a black man, while submerged in Olney River

Time was loud

The writer and psychiatrist Zebib K. Abraham on breaking free from the stifling demands for efficiency and learning to lean into time at the WritersMosaic Villa Lugara retreat

Wow, diaspora for real

Aniefiok Ekpoudom reflects on diaspora and the fantasy of return through conversations with friends and strangers

Love forms

The experience of silently reading Claire Adam’s Love Forms is one of immense and daunting loneliness

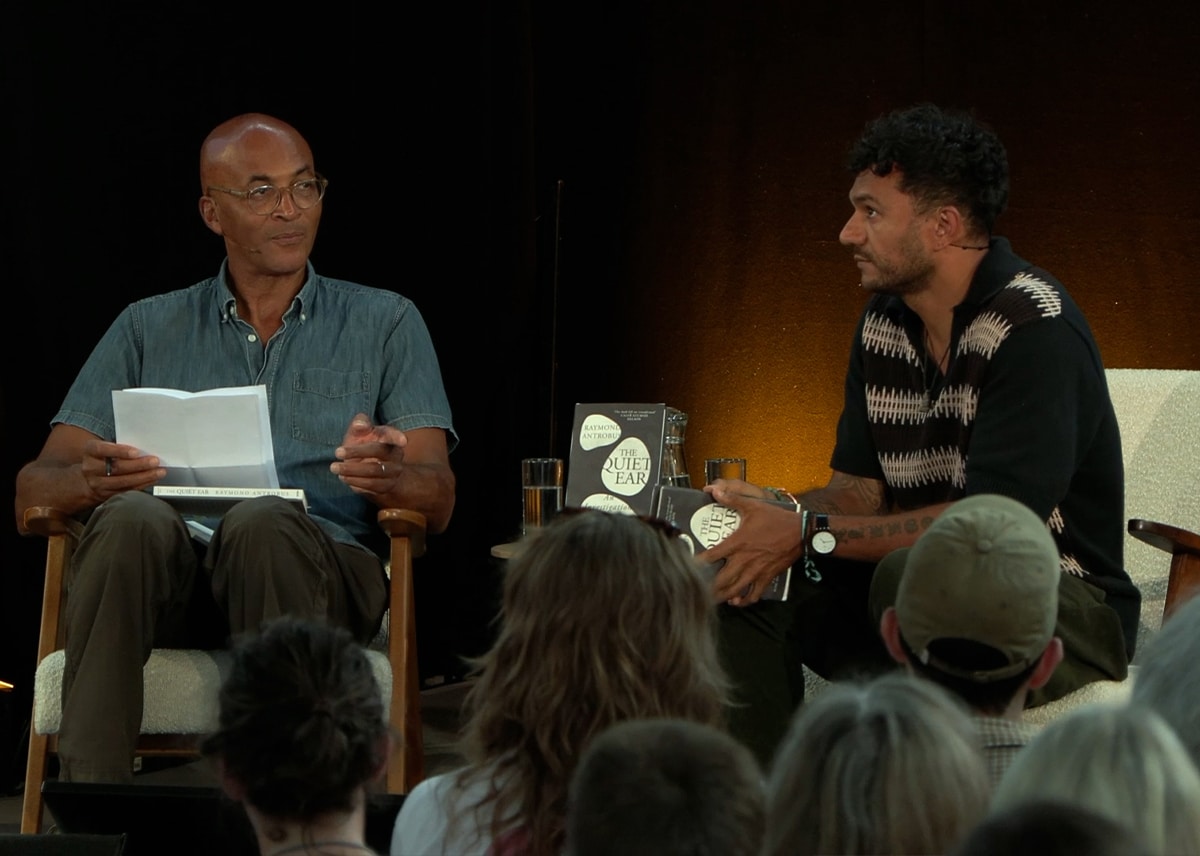

The Quiet Ear

The Quiet Ear by poet Raymond Antrobus explores what it is to be deaf in the world of the hearing through his own upbringing and the lives of other deaf artists

Nowhere

Khalid Abdalla’s one-man show Nowhere, raises questions of 'Who do we feel responsible for?' and ‘What [is] a life worth?’

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps