Poetry as a Container for Grief

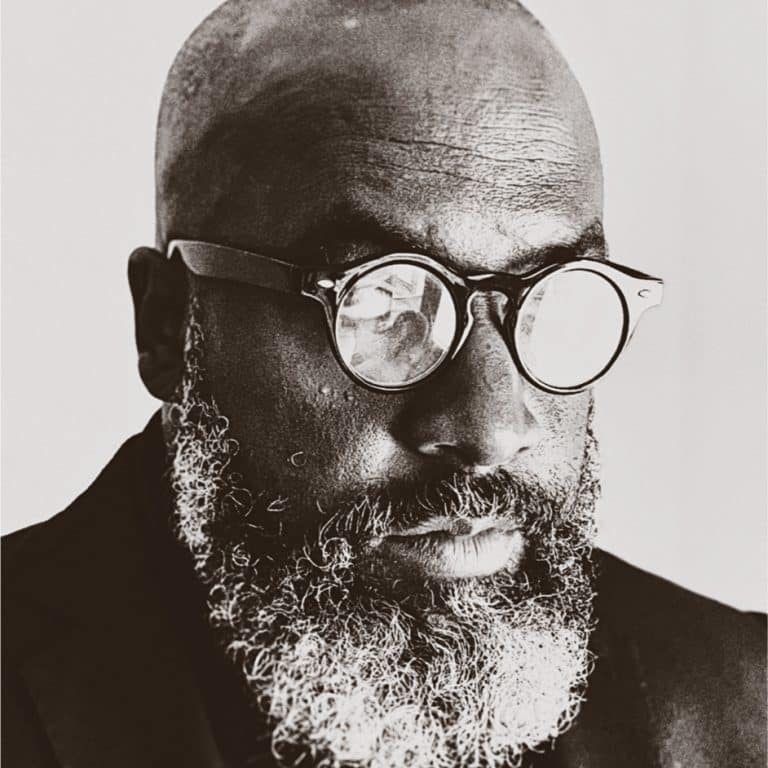

Roger Robinson

1.

In the mid-90s, I was in a long-term relationship that was slowly dying. I no longer had the energy to keep it alive. Around that time, a bombing in Luxor, Egypt, killed many tourists, and flights to Egypt plummeted in price. My partner, excited, suggested we go. I said no. She argued. I lacked the strength to resist, and so I found myself on a plane to Egypt.

Despite the tension, I enjoyed Egypt. While we were there, she suggested that we take a camel ride into the desert. Being risk-averse, I declined. She argued again. I relented and soon found myself riding alone on a camel while she rode with the guide. Through some trick of poor translation, (and even though I objected strenuously) we were headed for the Sudanese border, six hours away. The camel quickly sensed that I would not thrash it with the stick provided and took full advantage, alternately freezing in place and galloping uncontrollably. Eventually, I lost sight of the guide and my partner. Night fell. The desert temperature dropped. Off in the distance, I saw lights.

The camel trotted toward what turned out to be a funeral procession. Grievers were ululating in ecstatic sorrow, and the flickering lights of their torches created a haunting, mesmerizing scene. The camel walked straight towards, into and in between their funeral. I tried everything – pulling the reins, shouting – to stop it, but it stood still among them. To the mourners, it appeared I had interrupted intentionally. Stones flew. One grazed my head. I crouched down, ashamed not just because of the intrusion, but because I had let myself be coerced into the desert in the first place.

A boy eventually led me and the camel by its reins to a nearby road. I sat for about an hour on the curb at the edge of the Egyptian desert. There I began to grieve the relationship. My predicament symbolized its death. My grieving felt like a deep sadness. It was beyond crying; it was an acceptance that we were not going to be together. It felt terrible at that moment, but as bizarre as the situation was, it brought me to some considerable resolve. It had ended, and I would be alright, even though the moment was painful.

I could still see the lights and hear the screams of grief from the funeral I had disrupted in the distance. That display of grief, raw and public, reminded me of Caribbean funerals I had seen growing up, where mourners would throw themselves on caskets and roll in the dirt, only to appear later, clean and composed, at the repast. What did that moment of ecstatic grief do for them?

Sometimes I think poetry can offer those slippages of sorrow, a portal through which grief can leak without becoming an overwhelming forlorn broken dam. The poem can end. The book can close. And in that, poetry can become a container in which one’s grief may rest.

2.

When George Floyd was murdered in the midst of COVID lockdowns, I felt like I was strapped down in a horror show of Black death. I could not even look at my phone without encountering it’s brutality and its aftershocks. I called friends to tell them I loved them, leading to shared tears over the phone. During that time, mortality felt personal. Every racist slight I had buried for decades surfaced with added strength.

To survive, I disconnected. I cleaned my house. I organized my books. I told myself: Be analogue. Do not become a Black death addict. I turned to poetry for solace. A single poem by Lucille Clifton called ‘Won’t You Celebrate With Me’, just fourteen lines, saved me.

That is the thing about poetry. It can contain your grief. It can hold it lightly, safely, allowing it to breathe outside of your body. That externalisation through poetry can help to prevent or reduce an interior implosion.

Watch on YouTube: Poetry Everywhere: “won’t you celebrate with me” by Lucille Clifton

Read full text at The Poetry Foundation: ‘Won’t you celebrate with me’

3.

I have often thought about the show Finding Your Roots, where people uncover ancestral histories. Pharrell Williams once discovered that one of his ancestors was a child slave. He broke down crying. He had never met this person, had no photo, yet he grieved. Is it possible to mourn people we have never known? Those lost in wars, in slavery, in tragedies like the Twin Towers or Grenfell? Is that a kind of grace, a form of honouring?

Sometimes I write poems that bring me to the brink of grief, even though I know parts are fictional. The emotion is real. Maybe that is what poetry does. It gives us access to emotional truth.

William Carlos Williams once said, ‘No ideas but in things,’ meaning poems should evoke through imagery. I would adapt that to say, ‘No ideas but in truth.’ Not factual truth necessarily, but emotional truth, and honesty that requires deep self-knowledge.

The poem I wrote called ‘A World War Two Soldier Has Doubts on the Frontline’ brings me to tears most times I read it, because it makes me grieve for generations I didn’t even know, and the poem ‘Revenge’ by Taha Muhammad Ali makes me grieve for his relations and generations I have never even met.

Taha Muhammad Ali reads Revenge at the Dodge Poetry Festival

https://lithub.com/revenge-a-poem-by-taha-muhammad-ali/

4.

My mother was a brilliant storyteller and an equally brilliant liar. But her lies were not meant to deceive. They were meant to get at deeper truths. Her stories, often told over food, had emotional accuracy. That is what poets do. They reveal the invisible. They carry the hard truths of a society – trauma, grief, struggle – and shape them into something that can be understood.

I often still read ‘Rain Light’ by W. S. Merwin that helped me to grieve my own deceased mother.

https://billmoyers.com/story/a-poet-a-day-w-s-merwin-reads-rain-light/

5.

Poets do the emotional heavy lifting for society, saying what others cannot. They have always held this role, from ancient civilizations to now. That is why poets are revered, why dictators want them silenced first. That is why names like Rumi, Hafez, and Homer endure. Poetry is not just art. It is a public service.

I called this essay ‘Poetry as a Container for Grief’. I used the word ‘container’ deliberately – something that holds. Something you can place your grief in, even if only temporarily.

Grief can be ongoing. It can be subtle or overwhelming. Poems often feel like prayers, bridges between emotion and something greater than ourselves. Not necessarily religious, but spiritual in their reach. They are a voice speaking into the silence, asking questions we are often afraid to answer.

Sometimes a poem comes to you fully formed, as if you were just a vessel. Those are the moments when it feels like God is in the next room. Grief, shaped by poetry, becomes not just sorrow but something profound. Something shared.

The seven lamps of writing

I write because I am, and I write because I am not

The lorry

'What if it was a phantom lorry, and my grandfather, who always showed an interest in my writing, had driven it here from the afterlife to make sure I was hitting my targets every day?'

In defence of Black History Month

Is it time to bring an end to the UK's Black History Month?

Steve

The film adaptation of Max Porter's novella Shy is not a story about middle-class adults rescuing troubled youth; the grown-ups aren’t okay

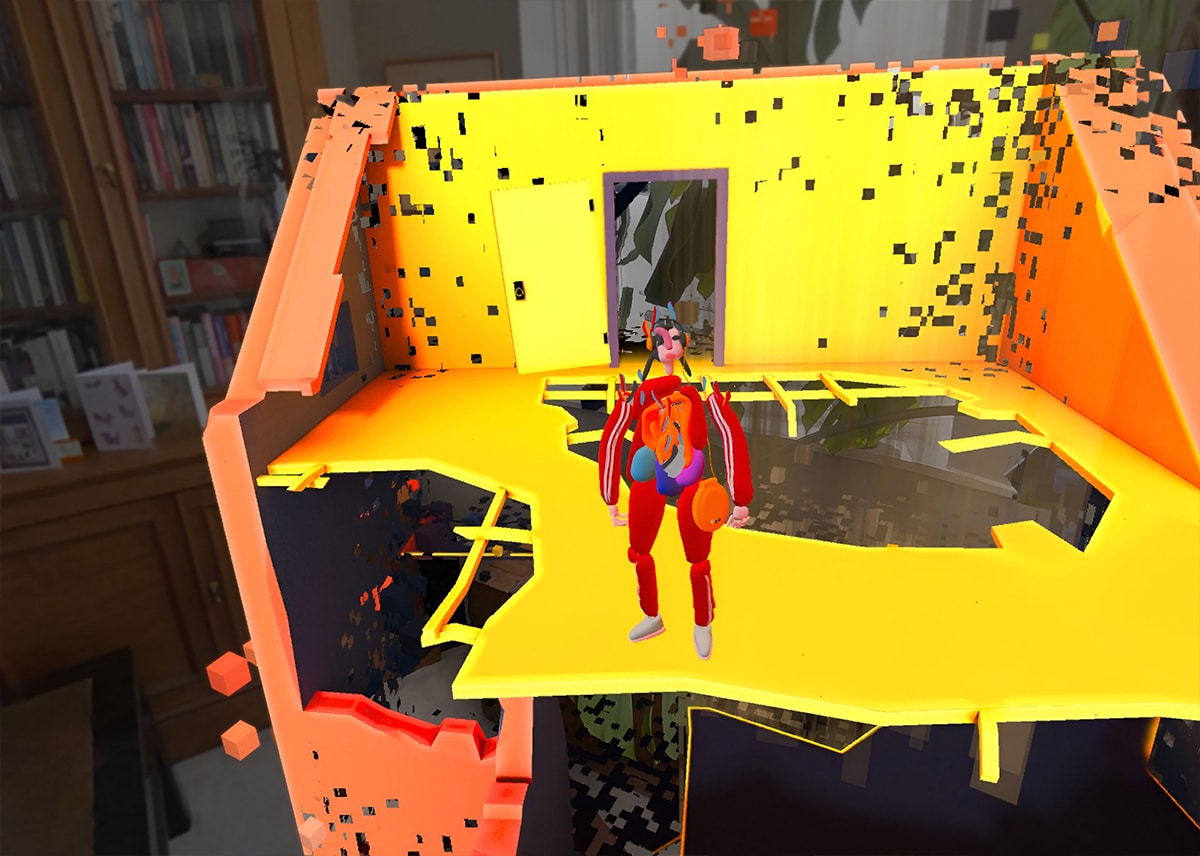

Impulse: Playing with Reality

A mixed reality experience by Anagram that journeys into the ADHD mind

Soon Come

In Soon Come, readers are treated to a narrative that has been, figuratively speaking, marinated in jerk seasoning

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps