It Was Just an Accident

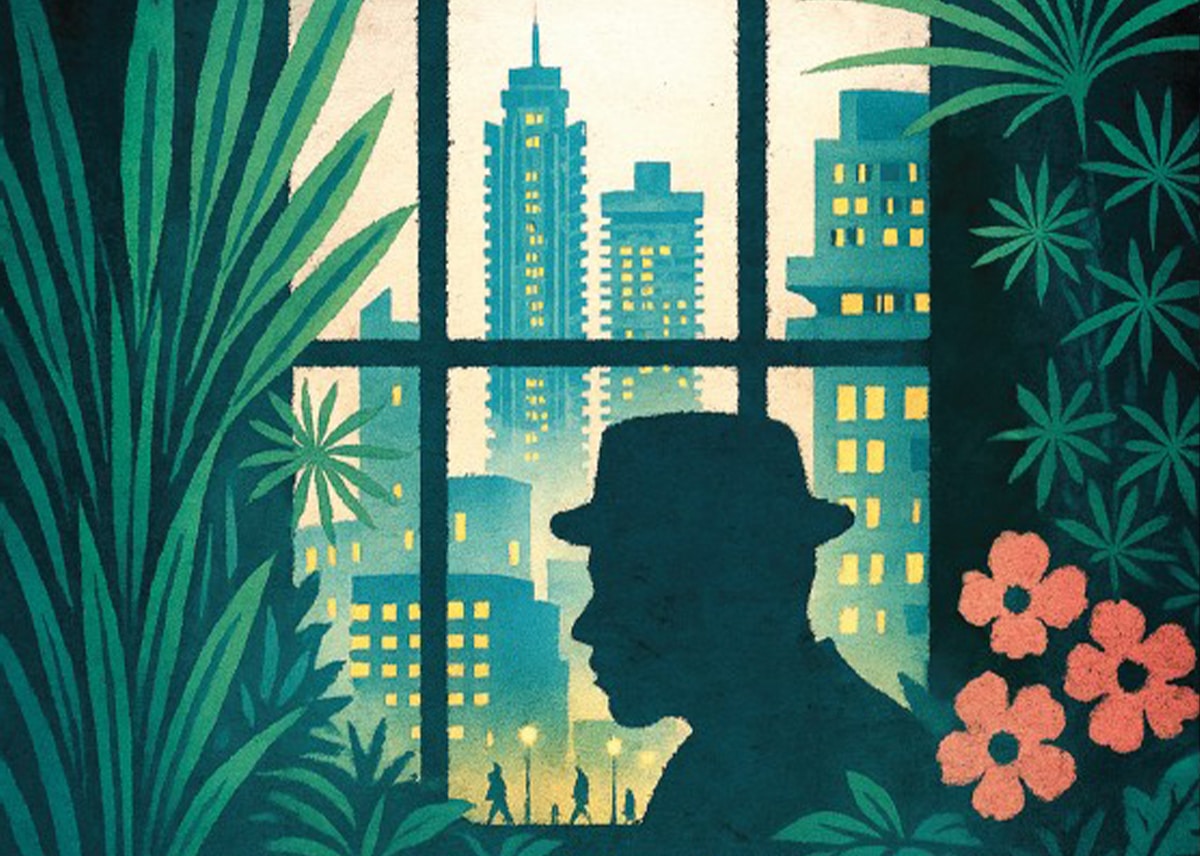

Directed by Jafar Panahi, 2025

The films that Iranian director Jafar Panahi has made since his filmmaking ban in 2010 have been defiant in every possible way. There is, of course, the mere fact of their existence: filmed covertly under the nose of the Islamic Regime and smuggled out of Iran on USBs hidden in cakes. There is the strain of anger that runs through all of the films; critiques of the regime’s capillary violence, told through often funny and tender stories of everyday people. And then there is their refusal of traditional narrative structures, leaning on metafictional devices in which Panahi becomes a character in his own films.

That is, at least, until his latest film, It Was Just An Accident: Panahi’s first traditional fictional feature in almost 20 years, it is also the first film he has made since his most recent period of imprisonment in Iran’s infamous Evin Prison in 2022 and the subsequent relaxation of his filmmaking ban. Yet It Was Just An Accident remains a classic Panahi film: made under illegal conditions – no permits sought, no censors consulted – and defiant to its core. The titular accident takes place in the first few minutes of the film, as a car with a husband, wife and their small daughter hits an animal on a dark road while driving back to Tehran. Seeking help at a nearby garage, the husband – whose every other step creaks with the sound of a prosthetic leg – is overheard by the mechanic, Vahid, who immediately identifies the noise as belonging to one of his torturers when he was imprisoned.

What follows is half farce, half thriller. Vahid follows the man, known to him only as ‘Peg Leg’, and violently kidnaps him, only to be thrown into increasing doubt as to whether this man is in fact the infamous Peg Leg. Dotting around Tehran in his van, Vahid collects a ragtag group of other released political prisoners – a wedding photographer, a bride and her hapless groom, and the wedding photographer’s reckless ex – each seeking to identify a man they only heard and never saw, and yet whose presence is burned into each of their minds.

It Was Just An Accident dispenses with the metafictional frameworks that have structured Panahi’s films since 2010, but it remains, in many ways, a study on the same concerns that underpinned those works: what it means to take action within suffocating conditions, and what civic agency in the face of state violence looks like. Formally straightforward, it remains nevertheless as existentially knotty as its predecessors, locked in the same liminal state of waiting, with certainty – by the nature of the violence being done – always out of reach. Whereas Panahi’s previous works had shades of Abbas Kiarostami, It Was Just An Accident’s closest correlation is with the work of Samuel Beckett. The scene in which the unexpected gang of avengers sit against their van next to a single tree could have been lifted straight from Waiting For Godot, both in its visual language and in its wry exploration of the loops that humans find themselves caught in, and the often empty promises of deliverance that they seek within particular narratives.

In It Was Just An Accident, this narrative is about the possibility of revenge, and what it might do for its traumatised characters. Less of a revenge drama than a ‘what-even-is-revenge?’ drama, It Was Just An Accident probes the relationship between individuals, the state and violence with determined humanism. Who takes ultimate responsibility for violence in an environment suffused with it? What does it mean to resort to the same actions as the people you hate? What happens if those are the only actions left to you?

Through these questions, Panahi threads the memory of revolution throughout his film, from the failed hope of the 1979 Islamic Revolution – whose effects the characters continue to bear – to the seismic social changes following the 2022 Woman Life Freedom movement. And yet Panahi refuses any easy answers, any catharsis that might come from simple political messaging. Instead, we are left with the impossibility of action, and the impossibility of inaction. Even under the most suffocating of conditions, Panahi tells us, we still hold our own agency. The very existence of It Was Just An Accident, and of his entire oeuvre of films that came before, is proof of that.

Mother Mary Comes to Me

'Who would expect such straightforward homage from an iconoclast and self-confessed sceptic like Roy?'

Concrete Dreams

A novel about doing rather than feeling, each episode in this long piece is discomfortingly realistic.

Phoenix Brothers

Sita Brahmachari's novel raises questions about agency, assimilation and solidarity for refugee children

Britain on the way home

'It is not their flags we should be afraid of, but their anger.'

Tell My Horse

My favourite book; an audacious, compelling and forensic expedition into Jamaican and Haitian socio-cultural lived experience in the early twentieth century

Between tradition and innovation: Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s cross-cultural currents

Drawing of parallels between the art of Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Kerry James Marshall

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Afro-Caribbean writer Frantz Fanon, his work as a psychiatrist and commitment to independence movements.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube