Red Pockets

Red Pockets: An Offering

Alice Mah

Allen Lane, 2025

Alice Mah has profound eco-anxiety. It haunts her, follows her from Canada to China to Coventry to Glasgow. She can’t shake it. She knows too much. As a professor of Urban and Environmental Studies, her most recent books are titled Petrochemical Planet and Plastic Unlimited. She doesn’t have the bliss of ignorance. Eco-anxiety bleeds into her thoughts, her lived moments.

In the first part of her memoir Red Pockets, Mah – a Canadian of Chinese heritage now living in Scotland – visits her family’s ancestral homelands in China, in part of a village known as the ‘Western Peaceful Place’. She is there during the Qingming festival (Qīngmíng jié), when people sweep the tombs of their ancestors: ‘Qingming means “clean and bright” in Chinese.’ To not fulfil this traditional duty is to invite the wrath of the hungry ghosts: grotesque, vengeful apparitions, who can reinhabit the world of the living if they are not properly tended to by their descendants, according to folk superstition.

The extended Mah clan also expect red pockets (hóngbāo) – like brown envelopes except prettier – full of cash from the Canadian visitors: ‘we were not seen as kin, but as banks.’ Her gifts of English tea are dismissed. She is consumed with unease, worried about causing cultural offence; she wants to please people, but short of building a new house in the village – as demanded by Uncle Mah (an unpleasant man who is not her actual uncle) – she cannot. In the end, she doesn’t sweep the graves. She worries about antagonising the hungry ghosts.

The pollution, ‘worse than the smog in Beijing’, burns the inside of her nose. She is anxious and overwhelmed both by the filthy air she’s breathing and the sense of environmental injustice – how, around the world, ‘petrochemical factories are located near to poor and marginalised communities.’ She says that the locals claim not to notice the pollution, but this is because the nitrogen dioxide has burned out their nasal cavities, killing their ability to smell.

This is not, as you can see, a fun read. It’s lucid and despairing, and to turn each page is to accompany Mah further into her eco-anxiety that, unlike a lot of other anxieties, is based entirely on concrete facts, knowledge and awareness. You cannot accuse her of making anything up. She feels fear, panic, anxiety throughout her body; her therapist suggests she stops catastrophising, limits her intake of news. ‘Everywhere I looked, I was reminded of death,’ she writes. Her panic ‘was the kind that burned quietly.’ Meanwhile, forest fires in British Columbia, her Canadian homeland, burn loudly.

As we approach the third part of the book with something that feels like heavy dread at the utter hopelessness of both Mah’s outlook and the world’s future, Mah herself intervenes. She rescues herself from crushing despair, and us from being dragged there with her.

Secular Buddhism saves her: ‘I believe in the possibility of transcendence.’ Here, we learn how she has always been sensitive, introverted, spiritually seeking; as a teen in Canada, she read Siddartha and ‘wore broccoli in my hair and long flowing dresses’, and as an adult in England, she attended Vipassana, the ‘monastic bootcamp’ of silent retreats.

Mah examines her fears, which stem from how ordinary everyday activities like swimming, breathing, sleeping, even praying (‘toxic pollutants from burning candles and incense, contaminating sacred spaces’) are all being poisoned by pollution. But, exhausted from despair, she has a realisation that ‘fear is also toxic’ and that there are ‘inner poisons, as well as outer poisons.’

Mah finds comfort in the ‘engaged Buddhism’ of the late Vietnamese Zen master Thích Nhất Hạnh, who said: ‘Once there is seeing, there must be acting. Otherwise what’s the use of seeing?’ Instead of despairing alone in Glasgow, she connects with ‘new friends in the climate movement who were committed to non-violent direct action – Quakers, Christians, doctors. We discussed climate despair over homemade soup and bread.’ It sounds like she found her local branch of Extinction Rebellion.

You feel relieved for Mah that she is no longer shouldering the terror of climate breakdown alone because, unlike most of us, she has been brave enough to look at it directly: to face it, and to realise how much worse it’s going to get. She finds some solace by acknowledging impermanence, and the ephemeral nature of being: ‘It was better to put joy out into the world, surely, than to add to the heaps of despair.’ She looks out at the distant wind turbines from her vantage point of Glasgow University’s tower and feels connected, not so much to her dead ancestors as to the here and now.

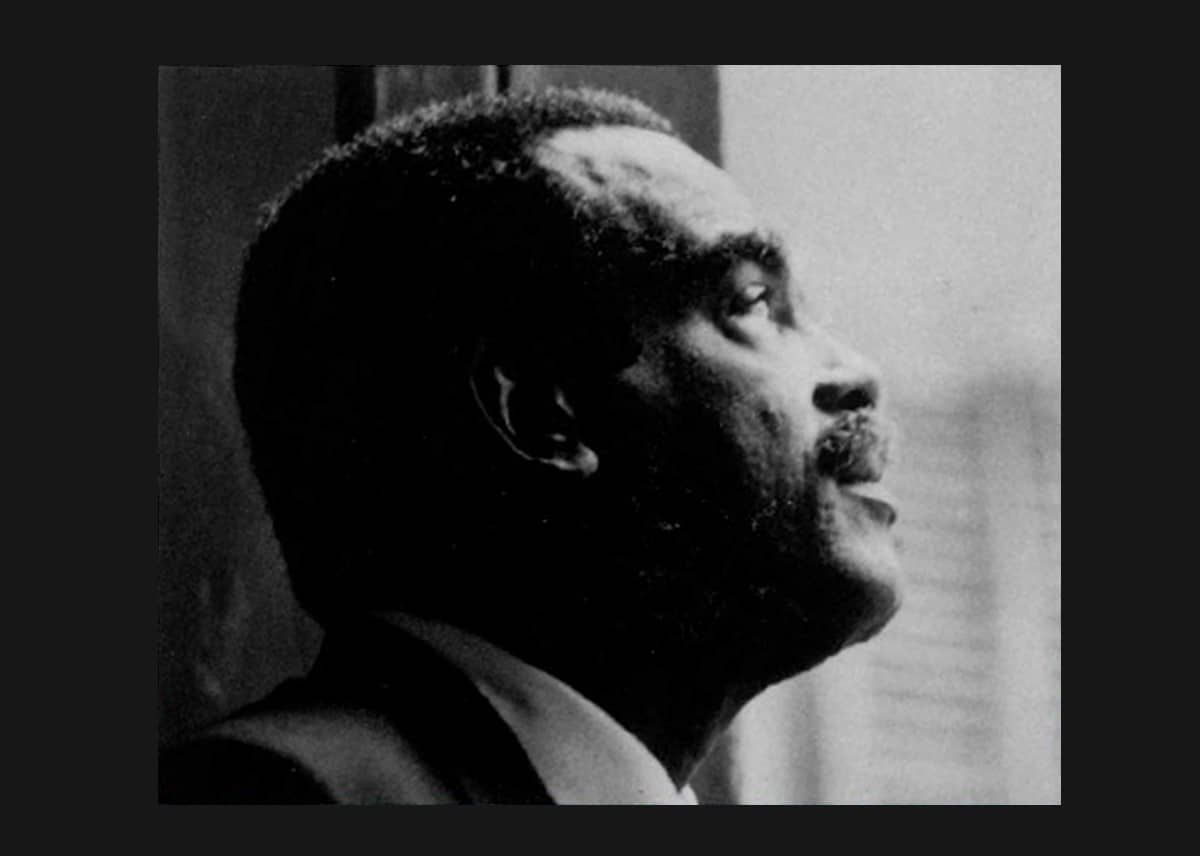

Donald Locke

A sombre and powerful showcase of Donald Locke's work over five decades

The Legends of Them

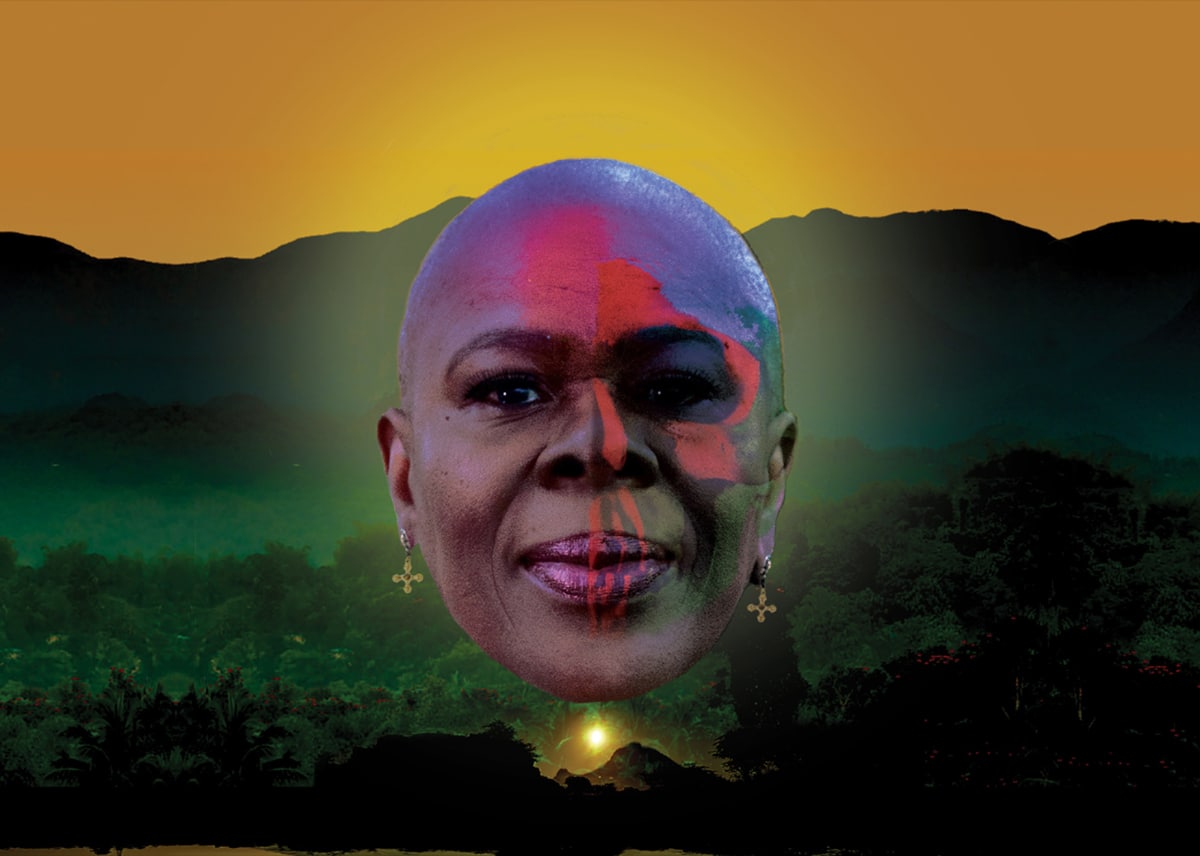

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny

The Booker Prize 2025 shortlisted novel is a beautiful exploration of love and loneliness between two young people

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

Yvonne Brewster remembered

Remembering the life and legacy of the pioneering Jamaican theatre director and actress Yvonne Brewster

Jodhpurs, Tweeds and Monocles

Inheriting the patterns of life marked into second-hand clothing

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps