Signs, Music

Raymond Antrobus

(Picador, 2024)

Review by Eve Grubin

In a 2021 interview about his poetry, Raymond Antrobus asks, ‘how do I disrupt one’s assumption of what sound is and what the function of sound is in the world?’ Antrobus continues to explore these questions in his 2024 poetry collection Signs, Music, the title signalling that the poems are interested in the relationship between symbols and sound. How can words (‘signs’) activate silence and conjure up music – that is to say: how might language communicate sound without hearing that sound? Can sound be imagined?

These questions take on a particularly profound resonance because the speaker of the poems, who we can assume is Antrobus as he has said that these are autobiographical poems, struggles with his hearing: he grew up partially deaf, and this aspect of experience reverberates beneath the surface of a book that addresses masculinity and fatherhood.

The book is structured as a two-part sequence poem. In the first section, ‘Towards Naming’, the father-to-be speaks to his unborn child telling his son that he watched a film ‘where vampires / had reflections. At first I thought it was a mistake / (a mist ache).’ As he speaks to his son, silent in the womb, he plays with language – a word gets broken down and takes on a new meaning. This moment suggests that the visual (in this case, the vampires with reflections) produces music in Antrobus’s mind: ‘mist ache’, words that indicate how he feels as an almost father.’ In a subsequent poem, he observes, ‘Today is my last Father’s Day as a non-father’: this ‘non-father’ aches to communicate with his almost-son who he speaks to as if through a mist.

The speaker considers his own late father in many of the poems, which weave in and out of lines that explore being a father to a new son: ‘So I sing through the wall of your mother’s pregnant belly, / ‘Three Little Birds,’ what my father sang / any time he saw my face troubled – ‘. These poems vibrate with a fragile vulnerability as the speaker meditates on worries about ‘fatherly failure.’ He writes,

‘I became fatherless at 26 and a father

at 35 and whenever I look out

the living room window I feel myself

become the child left alone in the house.’

These are open, spare, transparent lines of poetry that evoke humility: the opening poem that introduces the book begins with diffidence; the speaker acknowledges that he doesn’t ‘know the name of that tree’ he is asked to write about. His humble admission that he ‘can’t distinguish it’ calls attention to what we don’t know and to what we can’t distinguish, which for the speaker of these poems is sound. And not fully knowing sound often bleeds over into not knowing names. When he does describe the tree, as he does with this image: ‘bursting / with leaves like a loaded wallet, / autumn’s green and yellow receipts’, he uses a visual image of this unnamed tree to highlight abundance with both a simile and metaphor He creates a vision that is abundant with possibility and is associated with something not normally considered beautiful: a wallet full of receipts. And receipts are more abundant than money because they are ‘signs’ of the desired things that have been bought. This sense of plenty is a foreshadowing of the feelings of a father being lavishly blessed with a new son.

On the last page of the book, Antrobus shares a moving experience with the reader: ‘The first word my son signed / was music: both hands, fingers conducting / music for everything – even hunger’. The father revels in his son’s use of sign language to name ‘everything’ music, which highlights Antrobus’s project for this book: the poems ask what are words and names and what is their relationship with the things of this world? Why can’t ‘everything’, feelings, objects, thoughts, even hunger evoke the same music? They are all a part of the same life cycle; everything is connected. His son is teaching him this. The small child unknowingly addresses Antrobus’s questions about how signs conjure up music, how language might communicate sound without hearing that sound and how sound might be imagined especially in the book’s last lines: ‘I love how he clings / to my shoulders and turns / his head to point at the soft body / of a caterpillar sliding across the counter, / and signs, music.’

Love forms

The experience of silently reading Claire Adam’s Love Forms is one of immense and daunting loneliness

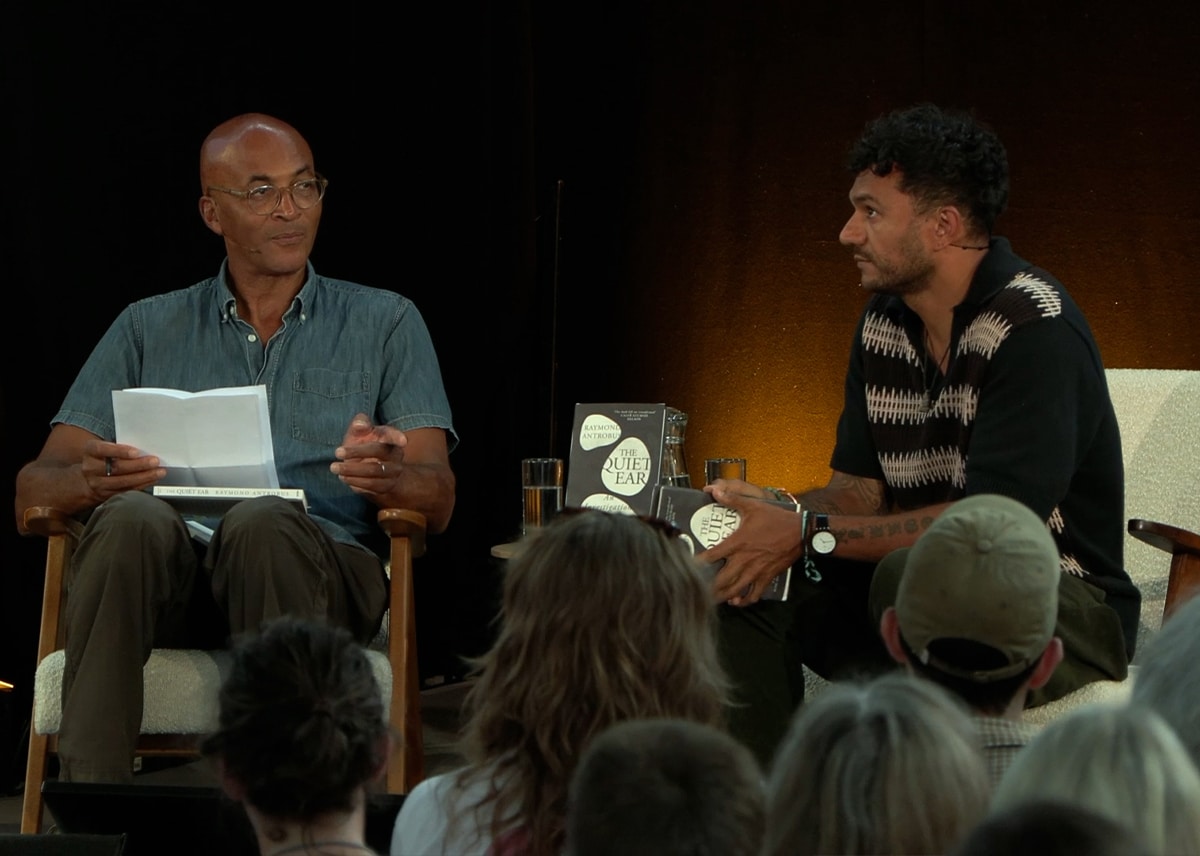

The Quiet Ear

The Quiet Ear by poet Raymond Antrobus explores what it is to be deaf in the world of the hearing through his own upbringing and the lives of other deaf artists

Nowhere

Khalid Abdalla’s one-man show Nowhere raises questions of 'Who do we feel responsible for?' and ‘What [is] a life worth?’

In Olney River

Exploring the feeling of being watched by white families as a black man, while submerged in Olney River

Time was loud

Zebib K. Abraham on breaking free from the stifling demands for efficiency and learning to lean into time at the WritersMosaic Villa Lugara retreat

Wow, diaspora for real

Reflections on diaspora and the fantasy of return through conversations with friends and strangers

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps