Soon Come

Kuba Shand-Baptiste

Dialogue Books, 2025

Review by Robert Donald

In Soon Come, readers are treated to a narrative that has been, figuratively speaking, marinated in jerk seasoning. The vernacular used throughout is accessible, as its liberally splashed patois is presented phonetically. In Jamaican parlance,‘soon come’ could be interpreted loosely: someone’s return might be imminent – a few minutes, or hours away – or unspecified i.e., sometime in the future. This looseness perfectly encapsulates the tone and tenor of the book.

Shand-Baptiste fashions an analeptic structure – i.e. making use of flashbacks. The opening chapter is set in 1959 in Notting Hill, then an overcrowded, slum district of many newly-arrived West Indian migrants, following the real-life funeral of Kelso Cochrane – an Antiguan stabbed in a racially motivated assault. The next chapter brings us to 2012 and, thereafter, we move back and forth until the story comes full circle, concluding in 2013 in a now salubrious Notting Hill.

This début novel draws readers into the complicated, flawed lives of its three protagonists: Mikey, Frank, and Judith – all Jamaican-born, but having subsequently made England home. Mikey seems perpetually cynical and depressed, demoralised by long, arduous hours sweating in the kitchen at his family’s Caribbean restaurant, endlessly washing stacks of pots and pans, and frustrated as he is unable to make a living from his passion: photography. Frank, a father of six with a gaggle of disgruntled baby mothers in tow, is a man who seeks ‘comfort in the form of a pair of big tits, or a bountiful backside’, and is awaiting deportation back to Jamaica. And fifty-something Judith, who leaves Jamaica for the first time to stay with her much younger cousin, Lisa, in Tottenham, folds under the pressure of her mother constantly nagging: ‘When yuh ah guh leff me an’ find a man?’ Judith reflects that, ‘Which man, it didn’t matter.’ It is her mother’s way of telling Judith to ‘get a life’. Prim and pious, Judith likes church, reading her Bible, cooking, and not much else.

Central to the action is Cudjoe’s, a Caribbean restaurant, a place where ‘When the food done, it done’. Here the disparate trio forge unlikely friendships. Food is ‘delivered with either a grin or grimace’, as customers are told flatly: ‘No, we nuh ‘av dat.’

The themes that emerge in the book are migration and marginality, explored through the lens of the protagonists as outsiders – whether in England or Jamaica. As Mikey, Frank and Judith battle with the authorities and British society in general, it opens up the proverbial can of worms. Do they, or don’t they, really ‘belong’? As each faces their own trials and tribulations, the notion of ‘soon come’ is apt, as their lives are, effectively, held in abeyance for different reasons. The one place where they are able to keep a less than welcoming Britain at bay is the safe space of Cudjoe’s.

A seminal moment, and one of the book’s most poignant scenes, comes when Mikey finally summons the courage to exhibit his work. A sizeable stash of photographs, spanning half a century and capturing every facet of the Black experience in Britain, has been hidden in a box in a basement for decades. But now, determined and with nothing to lose as he is in his seventies, ‘Mikey glances at the box, … smiles and says, “Soon come”.’

The characters have depth and, in spite of their foibles – irascibility (Mikey), piety (Judith) and ‘wotlessness’, i.e., worthlessness or irresponsibility (Frank) – are relatable and, for the most part, sympathetic.

Soon Come will put readers in mind of two other books: Small Island by Andrea Levy, and The Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon, which dealt with the precariousness of the lives of new arrivals from Jamaica to England in the 1940s and 1950s respectively. Soon Come, with its references to the Windrush Scandal and its ‘hostile environment’, is important, feels fresh and is engaging.

Kuba Shand-Baptiste’s début is impressive and noteworthy for its boldness and authenticity. Her gaze is unflinching, especially in her depictions of the characters’ sense of rootlessness and Britain’s ‘betrayal’. The book is timely in that regard, and Kuba Shand-Baptiste’s finely tuned observational skills bode well.

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

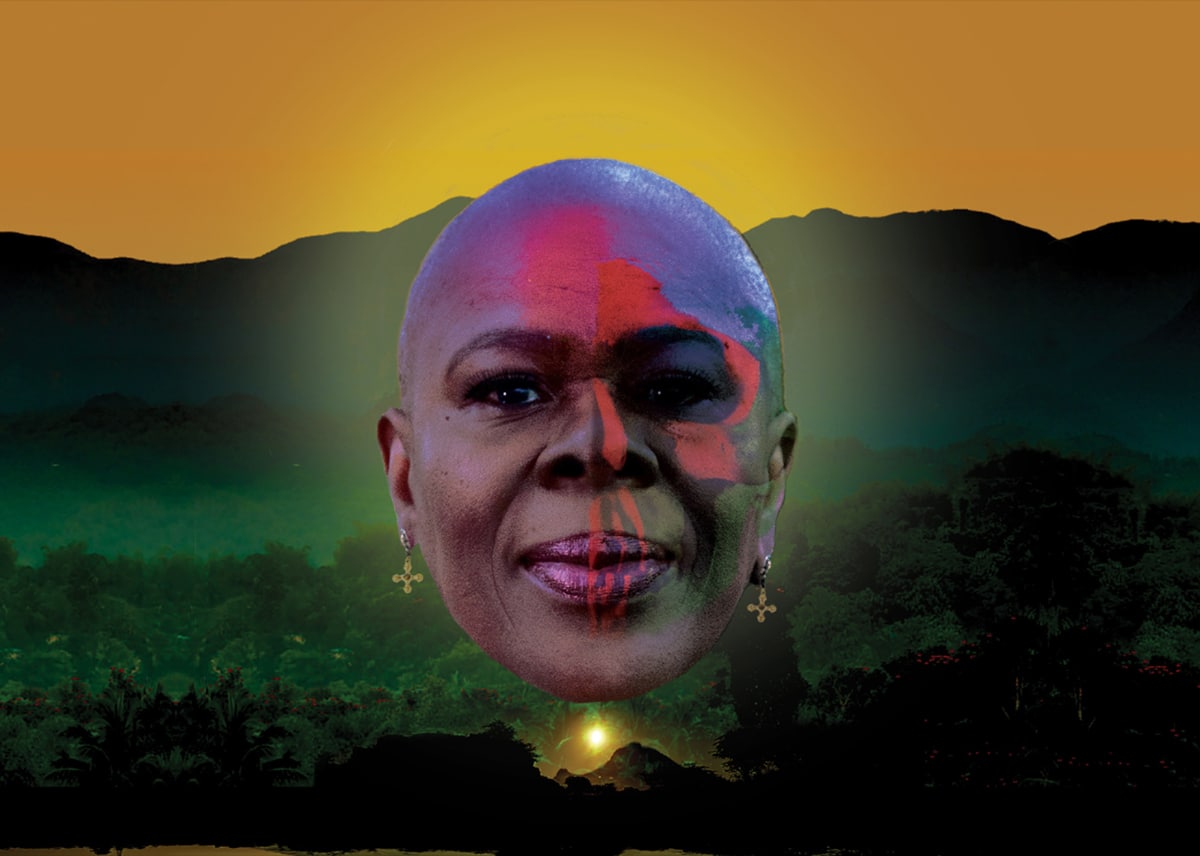

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny

The Booker Prize 2025 shortlisted novel is a beautiful exploration of love and loneliness between two young people

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

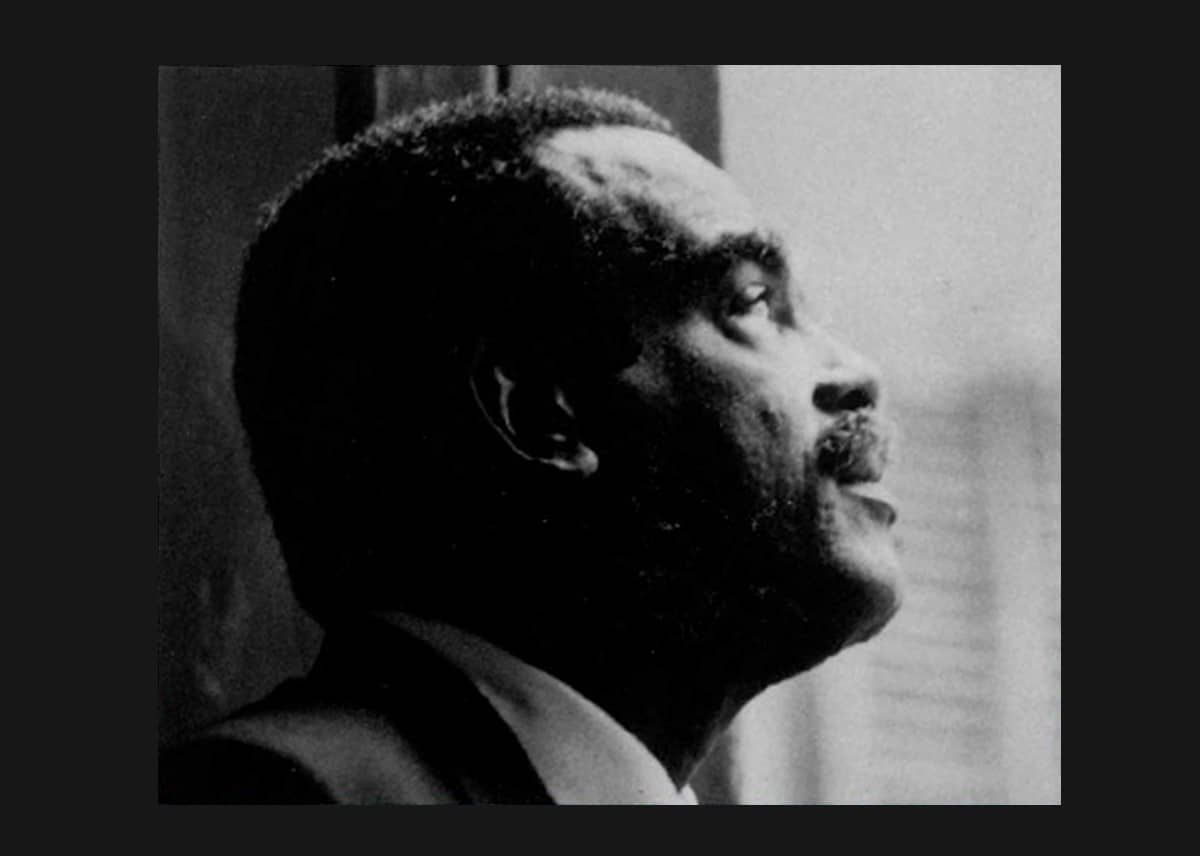

Yvonne Brewster remembered

Remembering the life and legacy of the pioneering Jamaican theatre director and actress Yvonne Brewster

Jodhpurs, Tweeds and Monocles

Inheriting the patterns of life marked into second-hand clothing

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps