In defence of Black History Month

We are in time of contestation, toppling and interrogation. The statues of yesterday are cast upon bonfires to loud cheers and the voices which might offer defence are subdued by uncertainty. That is, perhaps, not a surprise for the radical energies of the past have become institutionalised and, in that process, have lost clarity of purpose. The same can be said of Black History Month.

Should we continue to celebrate Black History Month in the UK? The intellectual violence perpetrated by Euro-America’s finest and dullest minds, led to the supposition that ‘the Negro is a man without a past.’ To be without a past is to be without civilisation, to be without civilisation is to be irrelevant to the past and future of humankind. It is either to be made extinct, by force or neglect, or subsumed.

This violence pervaded every aspect of British and American life. It is why American scholar Carter G Woodson established the first Negro History Week in 1926 that has of course since then expanded. BHM landed on British shores for precisely the same reasons why it was conceived by Woodson.

Imperfect granted, but BHM is part of our long push back against White supremacy. In recent years this push back has prompted a backlash by White supremacists who do not want to give up power. ‘Retain and explain’ is a more palatable version of silencing. We have moved on from this post-BLM. They want to and are doing more than holding the line. Openly and covertly, here and in the USA, reactionaries are challenging the hard-won consensus on a diverse national identity. They will be more than glad to starve institutions of funds that celebrate Black achievement. If the White supremacists win, we will be plunged back into the void which Woodson rejected. I urge the radicals of today to pause and consider that most unfashionable option – reform. For now is not the time, even if we had the power to do so, to retire Black History Month.

I stand before rows of students in the vast hall of a Bristol secondary school. It is Black History Month, and I have been asked to deliver an assembly. I sing, I crack a few dad jokes, and I read my most animated poems after whirling through an illustrated presentation of the great and good of our history. The students are inscrutable, particularly the students of colour. I will them to pose a question but clearly my powers of telepathy or mind control are faulty. I wonder for whom am I here? The kids? The teachers? The families? I am broccoli force-fed to kids who want candy. It is my second or third Black History engagement that year. At least the last school just allowed the kids to eat all the candy. Jay Z, Beyoncé, Stormzy, Rhianna these were the heroes the students selected. No wonder they nodded politely while I tried to share tales of dusty peace warriors from a pre-internet age.

In truth, even these awkward visits are now rare. I recall the halcyon days of racing across Bristol to join with African drummers, singers, and a plethora of Black artists as part of a Black History Month takeover. Those were the days when schools had money, and artists could holiday on the proceeds of a bumper month whilst putting aside the nagging thought that we might actually be injuring the very history that we wished to celebrate.

My experience among the ‘grown-ups’ is equally problematic. In a busy month filled with panel discussions, talks, shows, screenings and social networking events, only half are related in some shape or form to history. A fair number are events that just happen to fall within October and are branded as BHM with some lip service addition.

It is not the amount of activity that I question but the substance. BHM has become a period in which all things Black are platformed with scant regard as to whether they have or are likely to have significant historical significance. Figures from past and present popular culture are uncritically lionised with all the problems that this entails.

The ‘everything Black goes’ approach misses the rare opportunity for a rich popular discussion of our history which remains obscured by myth-making, buried in the academy or simply erased.

This state of affairs is – at least in Bristol – perhaps an inevitable consequence of the way BHM developed in the city. During my years of doctoral study, I worked as the librarian of a small African diasporic specialist library in the Kuumba arts project in the St Paul’s area. Kuumba was at that time funded by Southwest Arts and Bristol City Council. The role came with the responsibility for coordinating the Black History Month. My task was to create a spine of historically informed events. My colleagues and I would encourage the various Black third sector organisations to put on their own events. Inevitably some of these events would reflect the key business of the organisation or include celebratory activities that just happened to fall in October. This did not matter so much, providing there was sufficient historical content across the programme.

Mirroring the national picture, in Bristol Black History Month began to be taken up by what I would call, for brevity’s sake, White-led organisations. These partnered with Black arts and third sector organisations to create a city-wide offer. Out of these partnerships, new relationships were formed between artists, activists, and academics, some of which continue to exist today. I was among this early cohort who offered programming ideas, resources, and expertise across the city.

Then, as now, the take up created new questions and tensions. What was meant by ‘Black’, for example. To many statutory organisations, this referred to political Blackness, and they programmed accordingly. Pon road, Black took the vernacular understanding, to mean people of African descent. Indeed, beyond a few intellectuals and radicals, political blackness had never been truly accepted, especially in the 90s with the ascendancy of Afrocentric scholarship. Such questions were never quite resolved. Regardless, the collaboration between organisations such as Kuumba and Bristol City Council made a clear programme of activity available to the city. Imperfect and incoherent perhaps, but they at least ensured a degree of curation and care across the month for Black historical concerns.

The decline of Black arts institutions across the country has led to a corresponding decline in grass-roots Black history activity precisely at a time when many White-led organisations have embedded Black History Month into their programming.

Furthermore, a new generation often situated within, or in proximity to, White-led organisations have more recently begun to question the value of Black History Month. I get why. I remain active across heritage and culture during the month. 2025 is no exception. I share the frustrations of my older and younger peers. We have all growled at the last-minute scramble by institutions to come up with a Black History offer, and the narrowness and shallowness of the offer, the black-washing by organisations whose anti-racist copy book is blotted.

The staff at White-led organisations, listening to influential Black voices but lacking Black partners, are unsurprisingly unsure as to how or even if they should celebrate Black history Month.

Let us first consider the how. There is no means of ‘quality assuring’ the substance of Black History Month nor would that be desirable, because of the self-organised nature of events under the banner of BHM, but we can perhaps keep in mind the following checklist for organisations.

- Is it historical? Try to spread anti-racist work and non-history related events across the year.

- Is it inclusive? Britain’s Black community is increasingly plural. How do you balance interest and focus on new Black communities, on Black intersectional communities.

- Does it use popular culture to explore Black cultural artefacts beyond the iconic figure?

- Try to consider, as far as is age-appropriate, the fullness of Black humanity. Creating uncomplicated heroes can create disappointment when the fuller truth is revealed.

- Have you consulted or partnered with Black staff or partners? Surprise, surprise might encounter conflicting perspectives which may lead to you having to make a judgement call.

- Can you plan and seed your Black History Month focus throughout the year so that BHM becomes the final celebratory point?

- Share ideas and activities with partner organisations.

- If struggling with an external steer, use BHM to highlight figures of relevance to your institution and its work.

- How does your activity balance painful stories with celebrations of joy and resilience?

- Is your activity relevant to your community or your network?

- Does your activity make the invisible visible?

- Does it offer a new lens, perhaps a new conceptual lens, through which to see the world?

- Talk? Film? Theatre? Discussion? What means of engagement works well with different audiences? Start with candy and try to provide a whole meal.

This is a checklist for the now. It is tentative advice in a context where we have yet to maximize the use of the internet to centralise, share or disseminate BHM programmes locally or even further afield.

Perhaps one day a truly integrated national story would have transformed so profoundly what is understood as British history that Black History Month (or, indeed, Black British History Month) may no longer be a vital necessity. We are nowhere near that ideal if indeed it is an ideal.

Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation

The rewards of reading the deliberately complex texts of the Antillian philosopher Édouard Glissant

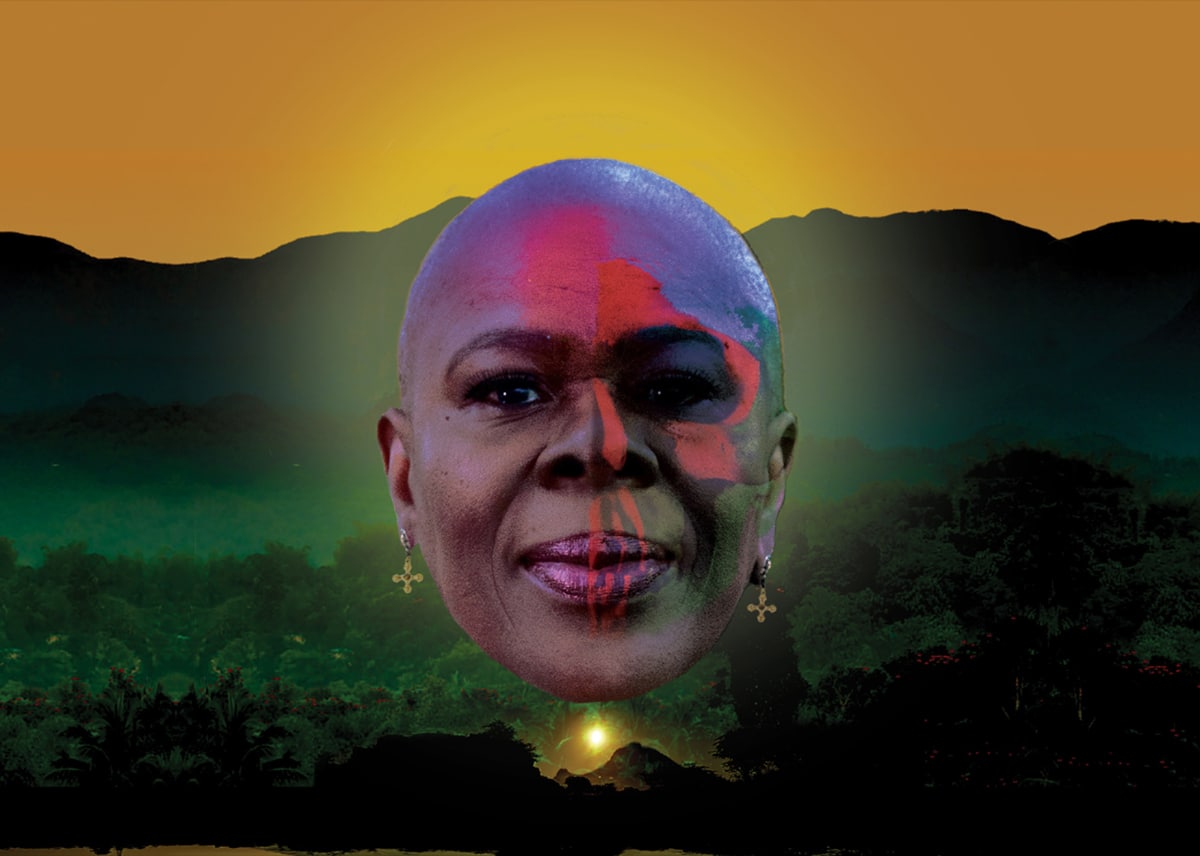

Yvonne Brewster remembered

Remembering the life and legacy of the pioneering Jamaican theatre director and actress Yvonne Brewster

Jodhpurs, Tweeds and Monocles

Inheriting the patterns of life marked into second-hand clothing

Red Pockets

Alice Mah's memoir confronts the climate crisis while dragging the reader back from the brink of despair

The Legends of Them

A dream-like production set inside the subconscious mind of a high-flying, female reggae artist

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny

The Booker Prize 2025 shortlisted novel is a beautiful exploration of love and loneliness between two young people

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps