Sade and the Quality of Restraint: a Zuihitsu

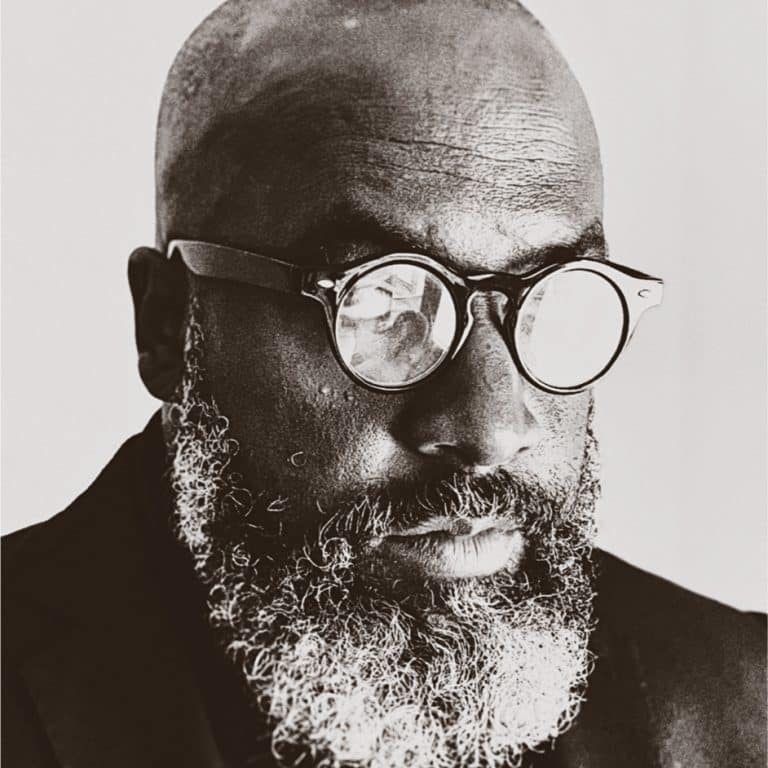

Roger Robinson

There was an eight-year wait between Sade albums Diamond Life and Lovers Rock.

*

Driving up to Wales on a family holiday with my wife and my ten-year-old son, at some point in every long journey, the Sade song ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ kicks in over the car stereo. And even though I am well used to my wife’s nearly pitch-perfect tones singing along, what I am not yet used to is my son’s high falsetto, singing at the top of his voice: ‘too good for me, you’re just too good for me.’

And we are all singing together, happy, and this is the moment I had prayed for when the doctors thought he might not live. When he was born, we spent the first fifteen weeks of his life, day and night, in the hospital, with our lives in a form of stasis. But now here we are, unified by life, love, and song.

Sometimes, with grief, what we need is a stopper removed. I find myself not crying at funerals, but if I’m listening to Sade songs one after the other, it pulls the stopper out, and all the tears from all the funerals of people I’ve loved begin to flow continuously.

Perhaps that’s what music is really for: to pull the stopper out and make you feel what you really feel, without protection, without control. Perhaps that’s a part of the utility of her restraint: the space made for listeners to place themselves in the song and emotionally participate.

*

Even her name is pared back: Helen Folasade Adu, or as most people know her, Sade.

*

Because I was taught, like so many of us were, that the way to survive is to perform. That if I could be charming enough, articulate enough, just vulnerable enough, then maybe I’d be allowed to stay.

I remember being the only Black man in a white office and making myself into an echo of what they found comfortable. I remember learning how to grieve with just the right amount of poetry so that my pain didn’t ruin their vibe. I remember laughing too hard, dressing too neatly, giving too much.

More became a reflex. And when I didn’t have more to give, I gave anyway, because if I’m honest, being liked by white people in my early working life became wrapped up in my head with economic and material access, in a mental state of scarcity.

*

Sade Adu is a master of the slow fade. Of the elegant exit. Of the no. She releases an album and then disappears into the folds of her life.

You won’t catch her on late-night television explaining her process. You won’t find her arguing with strangers on social media about what her lyrics mean. She does not tour unless she wants to. She does not create unless she means it. She does not offer access as proof of authenticity.

*

Sade’s trademarked look, jet black hair combed back, smoky eyeshadow, gold hoop earrings, and bright red lipstick on her full lips, is timeless, classic, and unconcerned with the zeitgeist.

*

Restraint, philosophically, is a deeply layered virtue. Across traditions, from Stoicism to Confucianism, Buddhism to existentialism, it’s associated not with repression, but with wisdom, presence, and the discipline to act (or not act) with intention. It may involve freedom through limits, awareness and discernment, moral courage, humility, elegance, and simplicity.

*

Sade’s stage performances seem to be a series of closed loops. Not closed-off, but she just doesn’t seem to need the audience’s approval to be satisfied by or energized through her performance. The audience, it seems, is simply an active observer.

*

But what happens when an artist simply refuses to play the game? Quietly, without a press release, by slipping through the spaces in the machinery and saying: It is to my benefit that you will not have all of me.

*

One of my music-obsessed friends, Angelique, argued that Sade wasn’t a real singer, that she just whispered everything and became successful through a combination of good looks and a distinctive style. I argued back that Sade used breathy phrasing to create intimacy and tension, and that her cool, controlled delivery served the emotional core of her songs. That she often opts for fragile textures over volume to emphasize vulnerability.

Angelique remained unconvinced.

*

The music doesn’t seem to purposefully bring you to emotional catharsis, but somehow, all these gestures toward restraint begin to feel monumental within the listener.

*

In my book A Portable Paradise, I wrote a poem called ‘On Sade’. Many people read the poem and thought I had actually met Sade (I hadn’t). What I was zooming in on was the idea that every facet of Sade seemed very much a purposeful symbol of restraint.

*

Duende is an emotional intensity in music beyond technique.

*

And so often, Black artists are asked not just to perform, but to bleed. Not just to speak, but to confess. The demand is for spectacle. The labour of translating one’s wounds into something legible. And then into something palatable. And then, somehow, into something inspirational.

There is no room for the off days, for the unshaped grief, for the parts of the story that never make it to the spotlight. There is only what can be consumed.

*

A never-ending grief.

*

To be permanent, without being prolific.

*

This is not protest in the way we’re taught to recognise it. There are no fists raised, no declarations scrawled across album covers. But it is a refusal all the same.

A refusal to let the public consume her faster than she can rebuild herself. A refusal to be always-available, always-decipherable, always on.

And maybe I didn’t understand that at first. But it cost something. There are parts of me I still haven’t gotten back. The soft parts. The ones I bartered away in exchange for understanding, applause, survival.

*

In a rare interview in 1984, Sade said: ‘You can’t stand on a soapbox and scream ‘understand me’. You just have to wait, and in time people believe the right things.’

This is what Sade was saying at a very early stage of her career, in the middle of the maximalist big hair, bright lights, and neon of the eighties.

*

And then I think of Sade. How she took the long road between albums. How she lived a whole life in the quiet. How she trusted that absence could be holy. That silence could be a kind of music. That the work doesn’t stop breathing just because you’ve stepped away from the mic.

*

I have been brought up by women (my mother and my aunts) who I cannot describe as paragons of restraint. A few examples: my mother once left a restaurant without paying, not because she didn’t eat the food, but because the standard of the completely consumed food was not high enough. Or my aunt, closing down one business only to start another the next day.

I could give example after example, but the net result is this: I wasn’t raised the kind of person to sit back and assess. Not the kind to take time to sharpen my axe before even thinking about cutting the tree.

*

What I’m learning, and it’s slow, and not always graceful, is that sometimes, restraint is the power.

The decision not to explain. Not to contort. Not to give away what hasn’t yet healed.

*

And just maybe, her restraint could become a life philosophy of mine.

A simplification. To amplify. Or think. Or, at the very least, to heal.

Note: a Zuihitsu is a form of literature that was popularised by Sei Shonagon in The Pillow Book in tenth and eleventh century Japan, incorporating personal reflections, observations, and snippets of varying lengths, sometimes with a sense of disorder or juxtaposition

In Olney River

Exploring the feeling of being watched by white families as a black man, while submerged in Olney River

Time was loud

On breaking free from the stifling demands for efficiency and learning to lean into time at the WritersMosaic Villa Lugara retreat

Wow, diaspora for real

Reflections on diaspora and the fantasy of return through conversations with friends and strangers

Love forms

The experience of silently reading Claire Adam’s Love Forms is one of immense and daunting loneliness

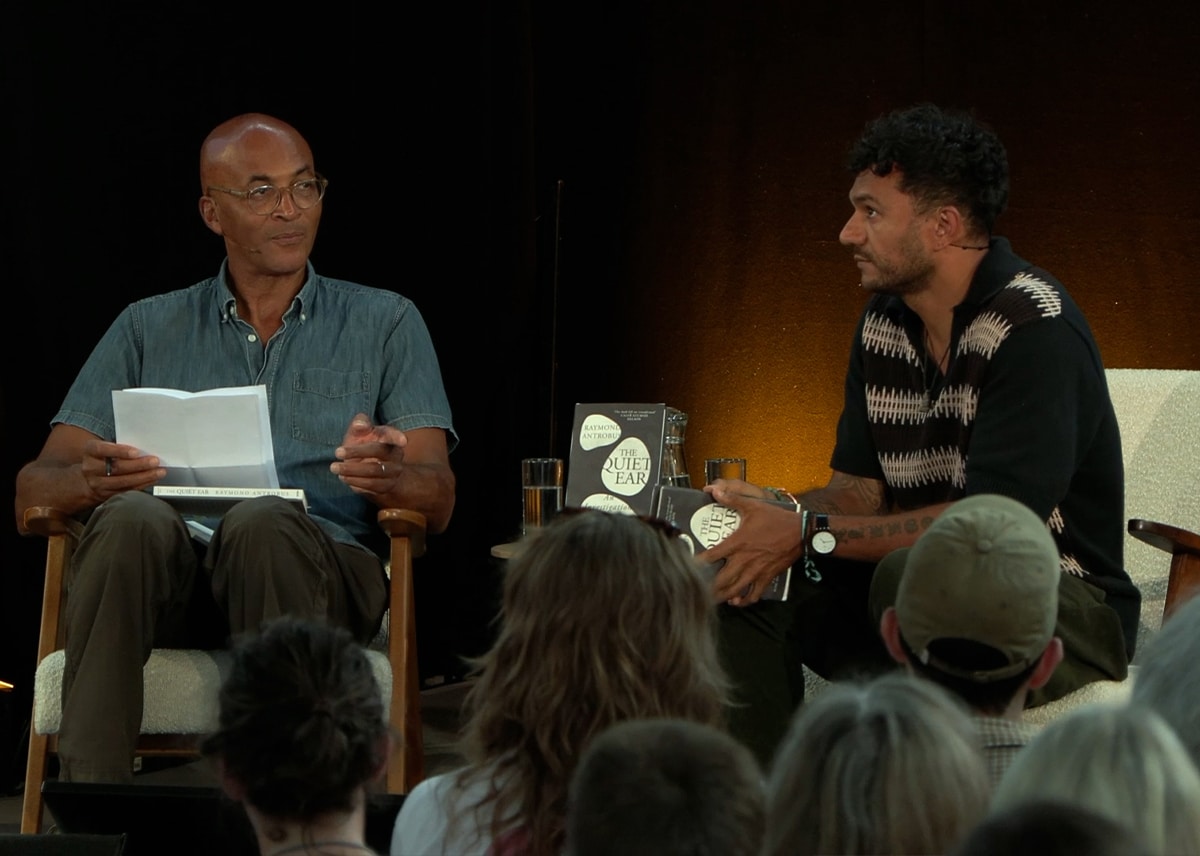

The Quiet Ear

The Quiet Ear by poet Raymond Antrobus explores what it is to be deaf in the world of the hearing through his own upbringing and the lives of other deaf artists

Nowhere

Khalid Abdalla’s one-man show Nowhere raises questions of 'Who do we feel responsible for?' and ‘What [is] a life worth?’

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps