The Black Mirror

Suhayl Saadi

She had a recurring dream. Recently, it had begun to appear on almost a nightly basis. She was peering into a large mirror set above the fireplace of a drawing room. Certain aspects of the scene had come to obsess her: the way in which, at the base of her full belly, the dancer’s dark bush of pubic hair seemed to come alive, almost like a nest of Gorgon snakes, as her body turned and twisted in the chorea which had taken possession of her; the intense blueness of the room, which could not be explained by the refraction of sunlight through the blown glass of the windows, nor by its reflection from the mirror; and then the low moan which seemed to issue, not from the woman’s perpetually opened mouth, but from the very walls of the house. The looking-glass woman had paused and had pressed her face up against the invisible plane, as though she was trying to push through into the room. It was, of course, her own face — the face of Ruqa Farrell, city dweller and estate agent of twelve years’ standing.

She turned off the engine and glanced at her watch. Nine thirty-four. She was a little early. He would be here in around ten minutes. That had been the arrangement. She had phoned him from home late last night — highly unusual, but at the last moment she had realised she had forgotten to confirm the time. She had felt a pang of disappointment when a woman had answered.

Even this early, the sunlight was growing stronger. She got out of the car and began to walk towards the house. It was warmer now than it had been when she had begun her journey, and as she reminded herself, Aradia Hall was south-facing. She removed her jacket and slung it over her arm, but then changed her mind and went back to the car instead. Opening the passenger door, she stretched over the headrest and tossed the jacket onto the back seat. No thief would venture this far out of town.

The dew had already evaporated. It had hardly rained for months, and the ground was like sand. She felt the give of the soil, and was glad that she had worn low heels. As she glanced back whence she had come, through the heat haze, she made out the rows of poplars which cut through the fields, the winding road which must have been laid down over an ancient bridle path, the hawthorn hedge which sprouted wildly in all directions, and the zinc roof over what looked like a cattle trough. Behind everything, the forest seemed to sway darkly, separating the lands which for centuries had belonged to the Hall from the abode of thieves and fools. On this, the far side of the pine and silver fir forest, one was as safe as it was possible to be these days.

She swapped hands, from right to left; her shiny, bull-skin briefcase was fat with papers. Maybe she would be able to get through some of them before he arrived. She glanced up at the plaque: 1678. The sunlight had begun to tease the verdigris at the base of the figure seven. Round the side of the house, beneath the gnarled branches of an unusually tall oak, was an old filled-in well and the petrified stumps of what once had been pear and fig trees. Now, thick clumps of knee-high red and white heather thrived among the bilberry bushes and the weeds whose names she did not know. Beyond this area lay the jagged remains of what once might have been a small steading. All that remained of these outbuildings were patches of beaten-down earth surrounded by stones which projected at odd angles from the ground.

The keys were deep in her handbag. They were made of archaic wrought iron and were enormous, of almost cartoon proportions. The one for the storm door felt smooth and warm, and was the length of her palm from knuckle to wrist. She felt the familiar frisson of excitement as she inserted the key into the lock, to the point where it came up against the resistance of the mechanism. Behind her, a couple of wrens chirruped and played about in the branches of a birch. Of all the properties on her list, this was the one Ruqa hoped would never sell.

She ought never to have taken the keys home — that constituted a breach of protocol — but it would have been so inconvenient to have had to drive in almost the opposite direction, all the way across town to the office, just to pick them up. On the phone, the woman’s voice had been deep and silky, and Ruqa had wondered whether perhaps she had already been in bed. She had pictured her: blonde, sleek and sultry, her nemesis. In her twenties, Ruqa had felt herself to be little more than a mirror to other people’s perceptions, and had tried to befriend one or two of these others.

Most of her friends had drifted away after they had had kids. It had not been intentional, it had not been anyone’s fault. It had just happened. And anyway, she had always preferred to live alone. It was her natural state, or had become so. Years ago she had tried living with someone for a while, and, as she kept telling everyone who subsequently asked, the music had not harmonised. Then, after a while, they stopped asking and it became the received wisdom. No-one said the word; no-one would have dared. But she could see it in their faces — it puckered their mouths and swept up at the ends of their sentences. Spinster. Spinner of thread. Spider.

She liked to sleep diagonally across the king-sized bed. She loved to push her feet outwards, feel the taut, cold cotton sheets come apart like the hide off a bull, and to extend all four limbs to full stretch so that if she had had a mirror on the ceiling (which she did not), she would have resembled a subtropical starfish. Skin, darker than olive, the pigment showing through the sheet, and limbs tapering sharply just before the wrists and ankles. Knuckly joints — very Indian. Her head, a fifth arm. Stargazy pie. Well, either that or a crucified saint. No, she thought, being a starfish is definitely preferable. Some nights, she slept naked just to feel the sheets caress her whole body. Sometimes, there was so much power in her limbs and her chest that she felt as though she might simply leap off the edge of a cliff, hover for a moment, and then, in defiance of all the laws, fly into the sunlight. Once or twice, she had physically stopped herself from trying this out. Deep down, she knew that she could have done it.

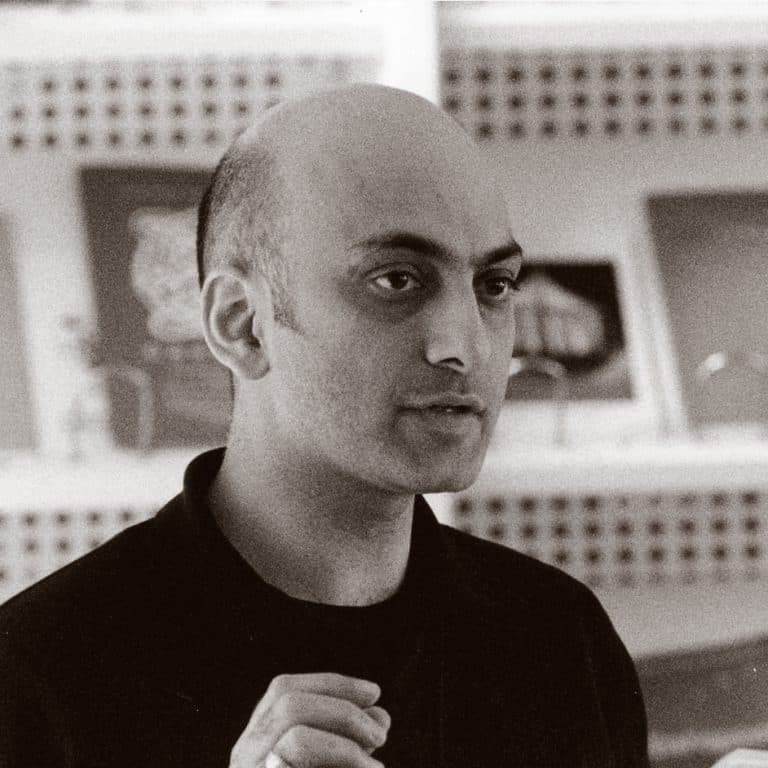

Suhayl Saadi

Suhayl Saadi lives in Glasgow, Scotland. His books include The Snake (1997), The Burning Mirror (2001), Psychoraag (2004), The White Cliffs (2005) and Joseph’s Box (2009).

My dead white male artist

A love story in three paintings

Lucha Libre

The spectacle of Lucha Libre, Mexico’s famous, masked, freestyle, professional wrestling, as experienced by Michael McMillan

Imperfect Speakers

Jhumpa Lahiri: Understanding Exophonic Women

The Booker Prize 2025: a public shortlist, a private thrill

The poet and translator Sana Nassari reflects on the excitement among the more than 2,000 people attending the Royal Festival Hall event announcing the shortlist for the Booker Prize 2025

Late Shift

Following nurse Floria over a late shift as her journey spirals out of control

Let the Fish Fly

A journey to an ashram in the Himalayas leads to a stronger understanding of self in Ekta Bajaj's novel.

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps