From Paradise to Afterlives

Afterlives: Bloomsbury Publishing (2020)

Paradise: Bloomsbury Publishing (2004)

Reviewed by Jane Bryce

In awarding the Nobel Prize to Abdulrazak Gurnah, the committee noted ‘his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee’. While most of his novels move between Zanzibar and England, in the case of Paradise and Afterlives the purview remains entirely mainland Ostafrika/Tanganyika (apart from seven pages set in Germany at the end of Afterlives). Though all the novels inhabit a world of extraordinary complexity, in which different ethnicities, cultures, social hierarchies and languages are braided together, by being set in a single continuous space at a particular moment of historical change these two share a peculiar atmosphere or emotional colouring. Characters are caught up in the sweep of history with little understanding of its meaning, only a sense of the past fading into obscurity and forgetfulness. In both, a child’s point of view dramatises a permanent confusion about the adult world. Both are shaped by journeys – the caravan to the interior in Paradise, the southward march in Afterlives – but also significant shorter journeys and local excursions which function as a form of self-exploration. In both there’s an enigmatic figure – the old gardener in Paradise, the master carpenter in Afterlives – who, by his steadfast performance of the work he loves with what tools he has, elevates it to a form of religious observance. Above all, cataclysmic historical events – two colonial incursions, two World Wars – are calibrated with intimate details of personal lives.

‘A war in Africa fifty years ago.’ These dismissive words, spoken by a German academic in Afterlives (2020) encapsulate the way memory of Germany’s World War One campaign in the country then known as German East Africa – Deutsch-Ostafrika – has been repressed. It’s 1963 and he’s speaking to Ilyas, a journalism student investigating what became of his uncle, an African soldier, or askari, who fought for the Germans in that campaign. The country he fought for came under British control after the war and was renamed Tanganyika; in 1963, it’s now independent and, in a year’s time, will unite with Zanzibar to form Tanzania. Ostafrika is obliterated, while Germany itself is divided into east and west. What sense in delving into that inglorious and half-forgotten past?

Yet this campaign underpins both the recently published Afterlives and Paradise, published 26 years earlier in 1994. That novel ends with a German military recruitment drive in Ostafrika at the start of World War One, and with the protagonist, Yusuf, escaping his life in bondage to a rich man to become an askari and fight on the German side. In an interview with the novelist Kamila Shamsie, Gurnah revealed that the scene of escape was where he began writing Paradise; the rest of the novel was ‘backstory’. Its ending, however, with Yusuf running after the German column, didn’t satisfy him. He wanted to know what happened to Yusuf and his fellow askaris and wrote Afterlives to find out.

In Paradise, a father gives away his young son, Yusuf, to a rich merchant, Aziz, as payment for a debt. Aziz takes Yusuf to live in ‘the town by the sea’ where he becomes, in effect, a slave. Yusuf, through whose eyes the entire story is focalised, persists in seeing Aziz as his uncle. Fellow-bondsman, the slightly older Khalil, puts him straight: ‘He ain’t your uncle.’ Scornfully uttered, the phrase resounds throughout the narrative as a talisman of unbelonging. Though Khalil is equally trapped by obligation, he has an adopted sister, Amina, living under Aziz’s roof, and knows his mother is in ‘Arabia’. Yusuf has no one and is, therefore, no one.

What he has instead are stories, beginning with the Koranic story of Yusuf (Joseph in the Bible) and Zulekha, the wife of Potiphar who falls in love with him. Both Yusufs are beautiful and enslaved, dreamers of dreams and interpreters of stories. Both are desired by a forbidden woman. As Gurnah has said, ‘Writing Paradise is when I began to understand that stories and telling stories are a way of describing the world you live in and how you understand it.’ In the absence of other markers, Yusuf must construct an identity for himself out of storytelling. Besides the Koran, there’s an echo here of the Arabian Nights, which Gurnah has told us he read in Kiswahili when he was growing up. The young Yusuf is drawn to the walled garden of the house that cloisters Aziz’s two wives, the Mistress and the much younger Amina. In the Koran, paradise is described as a garden quartered by rivers with a pool at its centre; for Yusuf, this earthly garden, with its furrows and mirror-hung trees, is a paradisical space of desire.

The story opens out when Yusuf accompanies Aziz on one of his trading trips into the interior, populated by people of diverse origins – Italian and Greek merchants, Masai warriors, mountain cultivators, German landowners, Indians, Arabs, Somalis and the ‘savage’ people of the interior. The first place they come to is ‘a small town under a huge snowcapped mountain.’ Look at a map and it’s easy to work out that he has travelled from Tanga, on the coast, to Moshi, at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro. By leaving these places unnamed, Gurnah endows the geography with a mythical dimension and enhances Yusuf’s sense of wonder at what he sees and hears. On a visit to the mountain foothills, he listens to his companions – Kalasinga, a Sikh, and Hamid, a Swahili Muslim – discussing paradise, each claiming it for their own religion, each determined that anyone who differs is a ‘savage’. Eventually, they reach Olmorog, halfway up the mountain, where a Zanzibari shopkeeper, Hussein, tells Yusuf: ‘Those mountains on the other side of the lake are the edge of the world we know… The east and the north are known to us, as far as the land of China in the farthest east and to the ramparts of Gog and Magog in the north. But the west is the land of darkness, the land of jinns and savages. God sent the other Yusuf as a prophet to the land of jinns and savages. Perhaps he’ll send you to them too.’

Through stories such as these, Yusuf learns about boundaries, the known and the unknown, myths of otherness and belonging, the European threat and Islam as a civilising force, with his namesake Yusuf in a prophetic role. If his own story had followed the Koranic template, he might have ended up as Aziz’s right-hand man and married to Amina. But experience shows him that paradise is a myth, and his choice is between different kinds of bondage. When he succeeds in traversing the garden and entering the house, he falls prey to the Mistress, with her disfiguring wound and her belief that his beauty can cure her. There, too, he gets to know Amina, who tells him, ‘I’ve got my life at least. But I only know I have it because of its emptiness, because of what I’m denied. He, the seyyid, likes to say that most of what propels the occupants of Heaven are the poor and most of the occupants of Hell are women. If there is Hell on earth, then it is here.’ The realisation that for him there is no Garden of Eden is what propels Yusuf to join the German schutztruppe and become an askari.

After the single point of view and intensity of focus of Paradise, the plurality of Afterlives signals a different kind of story. The opening section introduces a group of characters who seem at first to be unconnected to those of the earlier novel. We learn in some detail the genealogy and background of Khalifa, born of a Gujarati father and an African mother, who becomes a central node for all the ensuing relationships. He negotiates his way first under the Germans and then the British, becoming a clerk for another rich merchant and marrying his niece, Bi Asha, who is obsessed by the fact that her uncle has dispossessed her of her house. We are, we realise, in the same world as before, only the lens is wider. Historical events are woven into the fabric of a familiarly suffocating social system, built on unquestioned hierarchy and ruled by powerful men. The colonial presence is less seen than felt as a pernicious external force, characterised by alternating extreme irrational cruelty and unexpected acts of kindness. The humanity of individual German actors is glimpsed through the war-time experiences of two askaris.

The first of these, Hamza, takes up the story where Paradise left off: at a training ground for new askari recruits. He forms a strange, ambivalent relationship with his commanding officer, who delights both in belittling him and teaching him German, bestowing a lifelong love of the poetry of Schiller. The other askari, Ilyas, was rescued and educated by a German farmer after being kidnapped as a child. He regards the Germans as his protectors, joins the schutztruppe at the first opportunity and disappears forever. Before this happens, he takes up residence in ‘the town by the sea’ where Khalifa lives, and they become friends. At Khalifa’s prompting, Ilyas returns to his childhood home, discovers his young sister Afiya at the mercy of a family who are using her as a slave, and rescues her. When he joins the schutztruppe and returns her to the family, she is beaten so badly her hand is permanently injured. This time she is rescued, aged about ten, by Khalifa and, in the absence of her brother, goes to live with him and Bi Asha.

By the end of this opening section, the key characters are assembled, and a family of sorts has been formed. Already, as in Paradise, we have an uprooted child, a broken kinship network, a closeted woman, Bi Asha, nursing a dangerous wound. As we soon discover, Hamza, like Yusuf, is distinguished by his beauty. After he’s savagely attacked by another officer and nearly dies, his protector, the commanding officer, delivers him to a German mission station where he is nursed back to health. In the third section of the novel Hamza returns to the coastal town where he had lived before the war. Here, as he roams the streets looking for the house with the walled garden, the identification with Yusuf becomes irresistible. He gets a job with the same merchant who employs Khalifa and ends up living in the storeroom of Khalifa and Bi Asha’s house. Afiya, at first a shadow in the background, resists Bi Asha’s attempts to marry her off and makes it known to Hamza that she has chosen him. They become lovers and eventually marry.

Something has shifted in the narrative pattern. Though Bi Asha, the wounded woman, trapped and embittered like the Mistress in Paradise, is unable to find restitution, others succeed in doing so. The denial of kinship – ‘He ain’t your uncle’ – is reconfigured in a new set of relationships. Khalifa is always Baba (father) to Afiya, and becomes grandfather to her son, Ilyas, named after her brother, lost to the war. For Hamza, Khalifa becomes the brother that Khalil might have been to Yusuf in Paradise (note the coincidence of the similar names). Interrogated by Khalifa about his origins, Hamza tells him, ‘You want me to tell you about myself as if I have a complete story, but all I have are fragments which are snagged by troubling gaps.’ All Hamza can tell him is, ‘My father gave me away to a merchant to cover his debts,’ and that he was unable to find a trace of the merchant’s house on his return to the town. As a longtime resident of the town, Khalifa is able to fill in what happened: ‘The young man who ran the shop for him absconded with all the cash the merchant had hidden in the house. He ran away with the young wife, too.’ Out of Hamza’s fragments, Khalifa constructs a ‘story so impossibly rich that no-one would believe it.’

If Amina escapes the hell of Paradise, it is Afiya in Afterlives who above all achieves an unheard-of freedom. Because, at ten, she can read and write, she is able to send the note to Khalifa that enables him to rescue her. At eighteen, under Bi Asha’s malignant eye, she intimates to Hamza that he should approach her, by asking him for a translation of a German poem. She goes freely to his room as his lover and tells him when he should ask for her in marriage. Her name, Afiya, meaning ‘health’, is a key signifier for both these narratively braided novels. In Paradise, the Mistress tells Yusuf that ‘Your voice is so soothing… that God must have taught you to sing and sent you as an angel of healing.’ In Afterlives, it is Hamza who is healed at the hands of the missionaries, while Afiya’s damaged hand is healed by doctors. Later we are told how the British mandate prioritises education and health, and Afiya becomes an assistant to the midwives at the new maternity clinic. Only Bi Asha, when she falls sick, refuses all medical intervention, until Islamic prayers and traditional spiritual healing have failed. She dwindles and dies.

There remains a wound that cannot be healed: the loss of Ilyas, Afiya’s brother, who never returns from the war. When Afiya’s young son, also called Ilyas, starts to talk to unseen presences, again the spiritual healer is called, and pronounces that the boy is being visited by a spirit who lives in the house. ‘She is waiting for Ilyas… There will be no cure till you find him or find out about him, only then will the visitor learn to live with the affliction of his absence and stop tormenting the boy.’ So it is that we follow the younger Ilyas to Germany, where he looks for his lost uncle – who really is his uncle. The story he uncovers is one of a tragic identification with the colonial master. The older Ilyas went to Germany, married a German woman and died in a concentration camp in the Second World War. He had been working for the recolonization of Ostafrika under the Nazis, an unconventional but perfectly realistic reflection on what colonisation does to people. So at last another fragmented story is stitched together, and the wound, if not healed, is closed.

The younger Ilyas has become a journalist and a writer of stories as ‘a way of describing the world you live in and how you understand it.’ Through storytelling, these two novels dramatize the dispelling of an inherited trauma. Afiya in Afterlives, who might have been another captive like the young woman in Paradise, emerges into a life of her own, stands up for herself, makes her own choices. In finding each other, she and Hamza are able to knit together something they both need: a sense of belonging. The novel ends with a glimpse of the country as it modernises, the new technologies and greater opportunities that mark how people’s lives changed. A new kind of freedom has become possible.

Paris Noir

Artistic circulations and anti-colonial resistance, 1950-2000

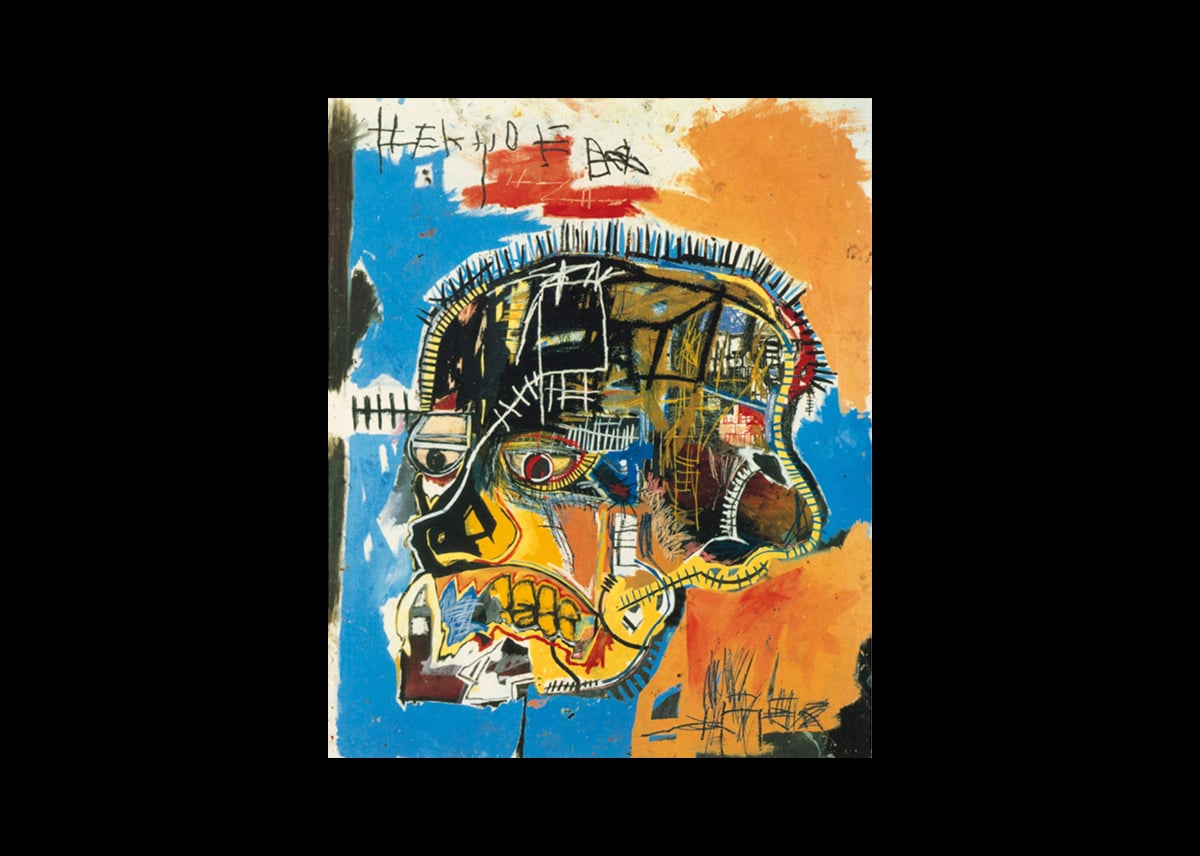

The New Carthaginians

Nick Makoha's new poetry collection inspired by the work of the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat.

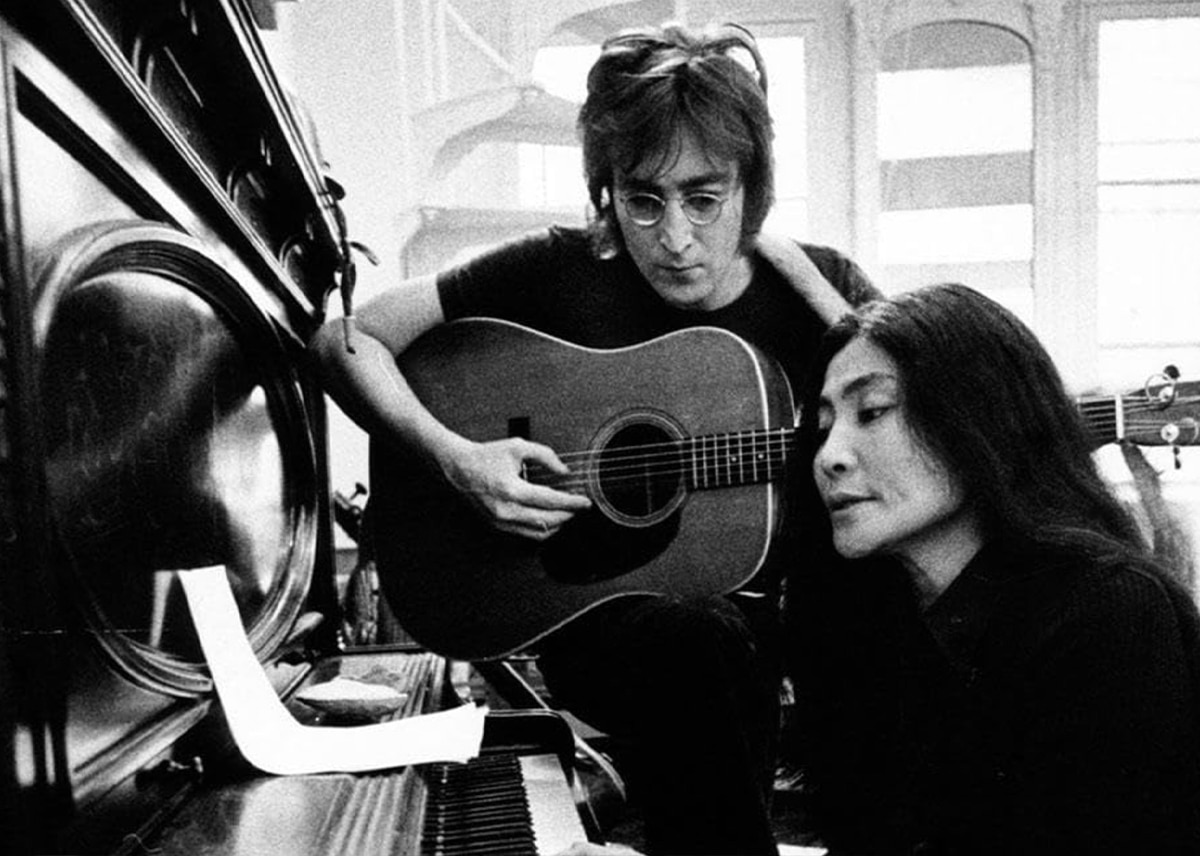

One To One: John & Yoko

Exploring the Ono-Lennon’s move into a small two room apartment in 1970s New York.

Before the Red Ink Disappears

Between a bomb and a hard place. Reflecting on the value of creativity in time of grave conflict in Iran.

What I value in the natural world

Tariq Latif reflects on how nature is ingrained in his spiritual fabric.

Zakazane pamiątki: Forbidden keepsakes

Maria Jastrzębska recalls discovering her parents' secret membership of the Polish Resistance during WW2.

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected collection, due from Bloomsbury in 2026.

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps