Small Things Like These

Directed by Tim Mielants (2024)

Review by Roger Robinson

Small Things Like These, the film adaptation of Claire Keegan’s novel (2021), might just prove a rare exception to the rule for book purists like me. Typically, I’d be among the first to proclaim – often loudly and before the credits have even rolled – that the book was better. But, with this film, there’s no need. It not only captures everything I love about the book but brings even more to the story.

I’ll begin by saying that this film is excellent (and I don’t use the word ‘excellent’ lightly). Not only does it excel in translating a novel to cinema, but it also stands as a triumph of cinema itself. It’s a triumph of acting – Cillian Murphy all but secures another Oscar, his name practically etched on it. It’s a triumph of cinematography, symbolism, screenwriting (if Enda Walsh doesn’t win Best Adapted Screenplay, I’ll eat my iPad), and of music, sound design, lighting, and costume. I could go on, but let me explain why.

On the surface, this film appears quiet and understated; in fact, very little seems to happen. It’s Christmas in 1980s Ireland, and we follow Bill Furlong, who runs a coal yard. As he goes about his deliveries, Bill is haunted by memories of his childhood: his mother’s death and his subsequent upbringing by others who offered varying degrees of affection. Now a father of four daughters, Bill is all too aware of the precariousness of his community’s economic situation and the struggles young women can face.

When he makes a delivery to a convent, which houses young pregnant or unwed mothers often held against their will, he stumbles upon one of these women locked in a freezing coal shed. Though the nuns pass it off as an accident, the incident gnaws at him. Soon, he’s torn between the social risks of intervening and his own moral compass. His wife, along with the entire town, warns him that crossing the nuns could jeopardize his family’s business and livelihood, yet he wrestles with his conscience, given his own past as a child taken in by strangers. The film quietly unfolds this moral dilemma, culminating in an understated but powerful conclusion.

Under this seemingly simple plot lies a rich tapestry of visual symbolism that adds profound depth to the story. Coal and coal dust become potent symbols of shame and burden. Bill literally carries coal on his back with every delivery; his hands and face are blackened by coal dust, which he scrubs off every evening in an effort to rejoin his vibrant family. Similarly, the young woman he finds at the convent is both trapped and covered in coal dust – coal, or shame, is part of her punishment.

The symbolism extends to the film’s setting. The narrow, deteriorating streets represent social neglect, and walking among them implies complicity in ignoring the community’s moral decay. These streets widen as Bill’s guilt grows, as though the space around him expands with his mounting awareness of his own responsibilities.

I could delve further into the film’s use of light and shadow – the present-day scenes bathed in darkness while flashbacks are set in natural light, echoing the darker era Ireland was in during the early 1980s. The Irish landscape itself seems almost a character, shaping the tone as effectively as any actor. All these choices translate beautifully from Keegan’s novel into cinema, creating a layer of symbolic richness that rewards close attention.

To sum up, the film is every bit as exceptional as the book (and I adored the book, so that’s high praise). It’s refreshing to watch a film that feels crafted with care, rather than designed to maximize profit. This is a film that truly matters, a film where every person involved seems to take their craft seriously. I urge everyone to see it now – it’s a work of quiet genius and beauty.

The Harder They Come

In the latest production of The Harder They Come at Stratford East, London, the musical depicts all of Jamaican life on stage with thrilling simplicity.

Love forms

The experience of silently reading Claire Adam’s Love Forms is one of immense and daunting loneliness

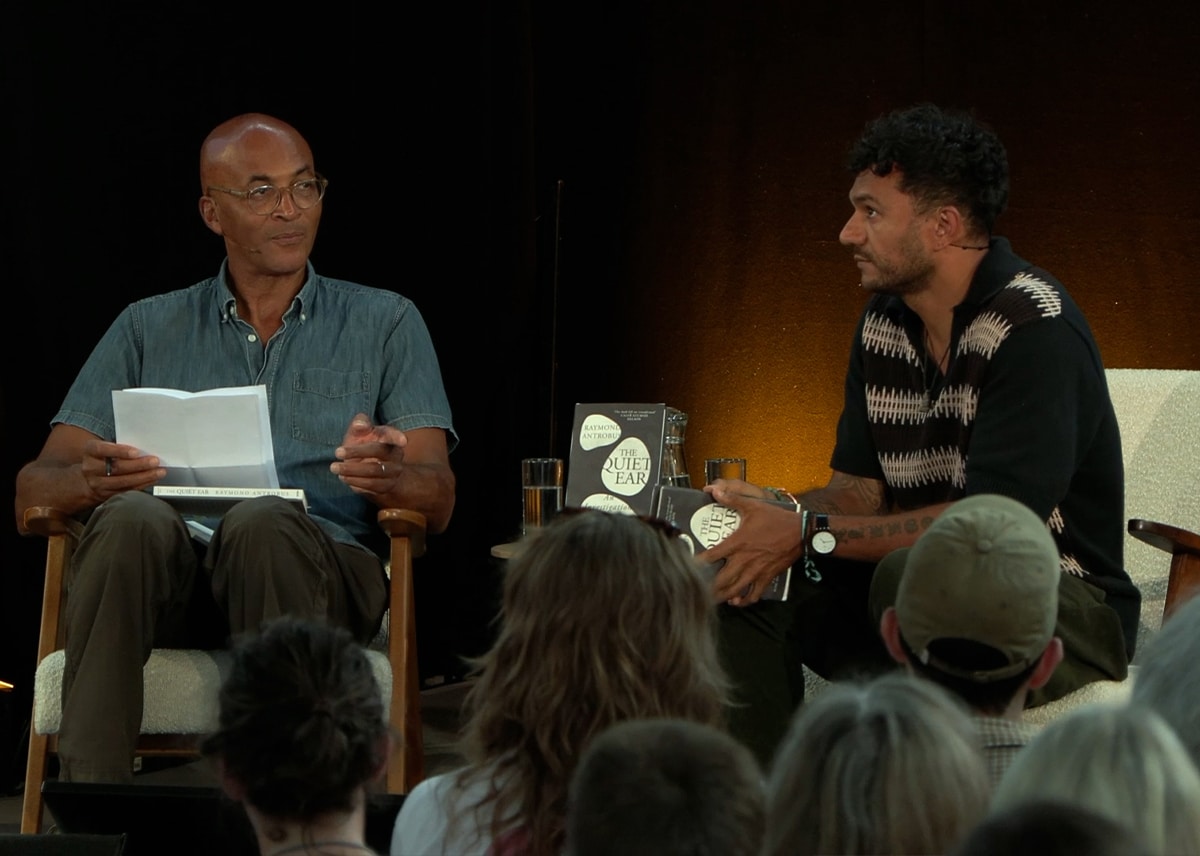

The Quiet Ear

The Quiet Ear by poet Raymond Antrobus explores what it is to be deaf in the world of the hearing through his own upbringing and the lives of other deaf artists

A close encounter with accents

An investigation of the consequences of speaking with a foreign accent in your adopted country

The last days

'A version of this life is ending. I’m in the last days. This may be the last essay I write as childless novelist.'

In Olney River

Exploring the feeling of being watched by white families as a black man, while submerged in Olney River

Preaching

'Preaching': A new poem by the T.S.Eliot Prize-winning poet Roger Robinson, from his forthcoming New and Selected Poems (Bloomsbury in 2026).

Walking in the Wake

Walking in the Wake was produced for the Estuary Festival (2021) in collaboration with Elsa James, Dubmorphology and Michael McMillan who meditates on the River Thames as we follow black pilgrims traversing sites of Empire.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps