Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

From the individual to the collective

I’m witnessing our current political moment in the West with despair and a sense of futility. I see individuals lost to groupthink, masses falling under the spell of delusions, convinced that the world is divided along lines of good and evil and that they must eliminate the scapegoated other. Whole groups are denying genocide as it is being carried out.

As a psychiatrist and writer, I’ve tried to understand what is happening through a psychiatric and psychoanalytic lens, but reasoning has slipped through my fingers. I’ve worked as an adult psychiatrist for years – through the height of the COVID pandemic, the Black Lives Matter protests, the return of Trump, and now, during this overwhelming and rapid shift into authoritarian populism. My patients tell me they feel guilty, helpless, scared, and numb. Trans patients are afraid for their bodily and existential safety. Children of immigrants are worried about the violent intrusion of the state. Some patients simply tune out of the news. I’ve tried to validate all their fears. Sometimes I get annoyed with their passivity, or I burn out on empathy. I try to guide my patients toward self-compassion, self-care, healthier relationships, and encourage them to create more structure in their lives. Still, they express a sense of hopelessness. They worry that individual acts of protest, dissent, and mutual aid are buckets of water being thrown onto an expanding inferno. Sometimes, I feel the same way.

Outside of my psychiatric work, people are starting to scare me; huge parts of society loom like overwhelming, unyielding, oppressive hordes. I’ve needed to make sense of it – to dig down into what drives us into oppression and tribalism. I’ve been stuck in traditional psychoanalytic thought: the individual, a strangely neutralised, apolitical, western model of the mind. I keep beating my head against a wall. There is no way out, or in, it seems. People are beyond reason, my fellow psychiatrists say; my colleagues are tuned out or feel hopeless themselves. We don’t know what to do as we watch people regressing, hardening, rejecting truth for delusion, gleefully and violently fleeing the complex to embrace the simple and secure.

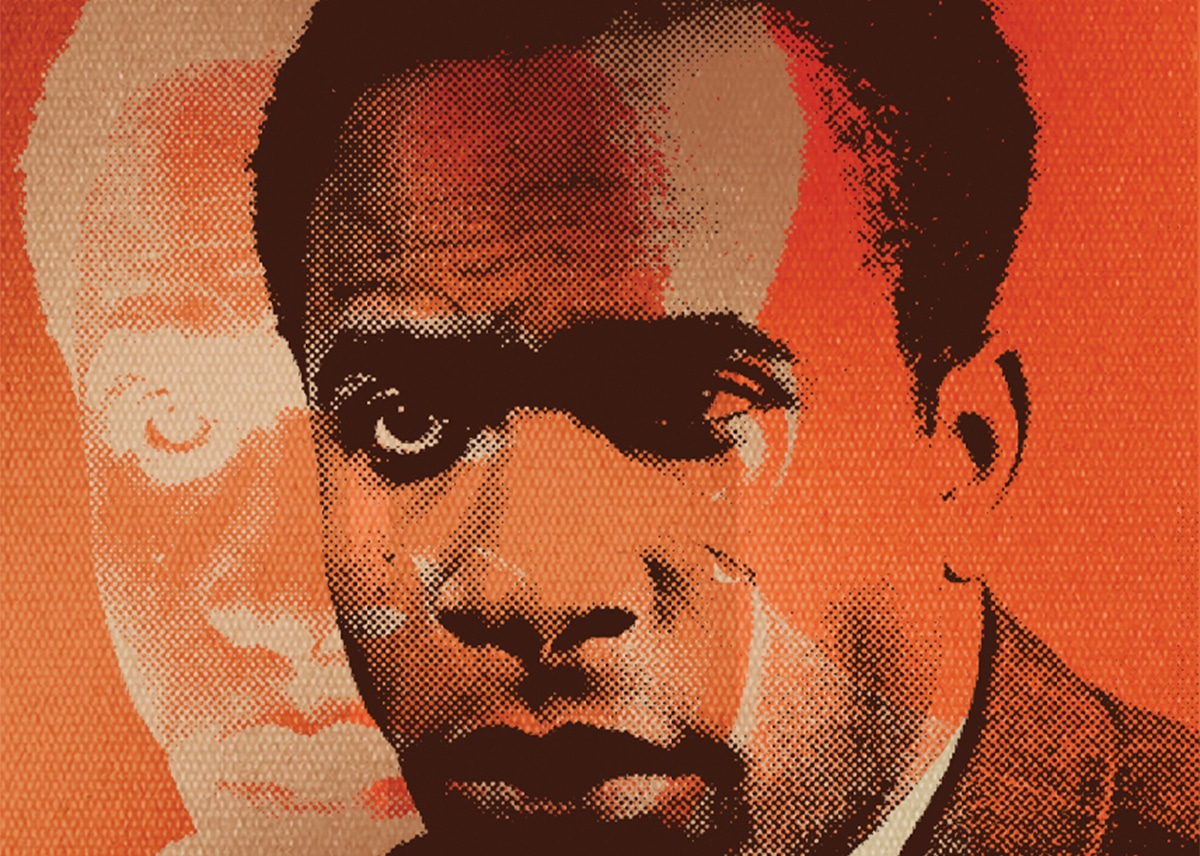

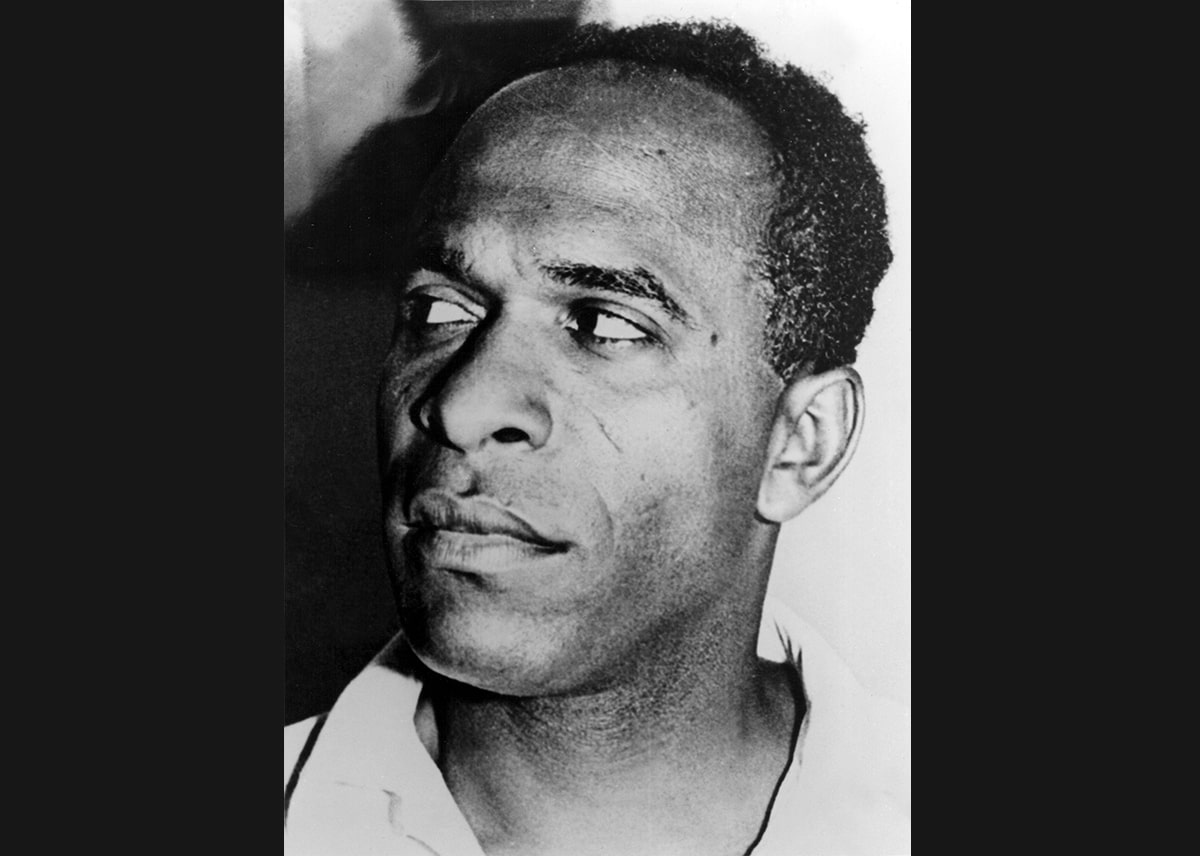

As I’ve tried to escape this trap, I’ve turned to the work of Frantz Fanon. A black man, a French West Indian, an anti-colonial psychiatrist, Fanon grew up in Martinique under French colonialism. He went on to fight for France in WWII, study in France, and eventually work in a psychiatric hospital in Algeria during its war for independence from France. His psychiatric perspective was rooted in traditional psychiatry and an awareness of cultural and political influence on our inner lives. Fanon’s work surprised me, confounded me, and challenged me. Specifically, I’ve been drawn to Fanon’s seminal work, The Wretched of the Earth, in which Fanon explores the group behaviour, identity, violence, and self-agency of colonised Africans – theories directly informed by his work with Algerians and the French.

With Fanon, I’ve begun to see a more complex picture of how people are affected by oppressive systems. Fanon understood that social circumstances shape our identity. The individual exists within the group, and the group indoctrinates the individual. This principle is often only superficially present in our therapeutic training, popping in as ‘cultural competency’ or ‘an awareness of marginalization’ instead of a vital reality in all our psyches: that we are shaped by man-made systems and our position in society.

I’ve learned that those who oppress others are driven to their deluded, terrible actions by their own fear and shame. That individual healing doesn’t just start within and spread outwards, but is also based in material realities; protection from violence, more resources, safety. Most importantly, Fanon has provided me with the insight that healing is not just individual, but an active and group process, requiring collective empowerment and political consciousness.

Fanon combined psychiatric insights and political awareness in his writings. His work stemmed, in part, from studying Algerian victims of colonial violence and French officers who tortured Algerians. He pointed out how colonialists, like the aspiring fascists of today, were driven by rigid fear, shame, delusional entitlement, and existential fear. Keeping Fanon’s theories in mind, I understand that people act out of a fear of annihilation. These oppressors are desperate for safety within the authoritarian group and try to achieve safety by annihilating the threatening other. If we pursue self-protection above all else, even those who believe themselves morally righteous can take up the mantle of oppressor. Those who are oppressed are left with feelings of hopelessness, inferiority, rage, and their own shame. Both the oppressed and the oppressor are isolated and afraid.

I’ve been overwhelmed as I’ve witnessed mass delusions; people denying human rights, science, decency. My patients describe watching the news and feeling a physical panic, disgust, self-critical thoughts for ‘not doing enough’. Fanon helped me see a potential solution: understanding our fear and shame, and then transcending it.

Fanon believed that the only way to heal the individual and break free of oppressive systems, which by their nature were rigid and violent, was an initial act of violent resistance: ‘The colonial regime owes its legitimacy to force […] “It’s them or us” does not constitute a paradox, since colonialism, as we have seen, is in fact an organization of a Manichean world.’

He believed violent rebellion would allow the colonised to grab their own agency; ‘violence frees the native from his inferiority complex […] despair and inaction.’ The oppressed can take back actual power, be active, and create change. Fanon’s theories were a fascinating contradiction – advocating violence yet deep humanism – and I struggle to reconcile with this ‘inevitable’ violence. Yet how else do people resist the realities of abuse, displacement, starvation, genocide? Who is legitimately allowed righteous violence? I believe that so much of his work, while universal, is also quite specific to his particular moment in history, his position as a French West Indian post-war thinker.

Fanon kept surprising me. Despite a call to arms, Fanon called for a complex and humanistic path forward. He advocated violent resistance but also encouraged the colonised to lean into a shared humanity with perceived enemies: ‘Racialism and hatred and resentment – “a legitimate desire for revenge alone cannot sustain a war of liberation”; and ‘people […] pass from total, indiscriminating nationalism to social and economic awareness.’

I thought Fanon’s insights would simply help me understand my patients. Yet I found Fanon, first and foremost, offered me a new way of seeing myself in these tumultuous times. I was the one stuck in hopelessness, avoidance, and shameful anger. I felt isolated. Traditional psychoanalytic thought and Western individualism, as well as my own tendencies, told me I had to work out these fears through therapy, self-contemplation and individual acts of dissent and resistance.

Fanon offered me more possibility. He helped connect my individual experience of defeat and helplessness with larger movements of collective action. I could talk to others, right now, and actively engage with collective efforts to feel more inner agency and empowerment. I have learned a simple fact: I can’t resist alone, and we all must make an active choice to resist injustice. As Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth, there is no ‘demiurge’, no ‘famous man who will take responsibility for everything.’ No one will come to save us. We are all, together, collectively responsible for what happens next. We must accept this responsibility and engage with each other. My engagement with mutual aid and social justice might contribute to higher-level change, while also feeding back into my inner healing and self-awareness. I can breathe a sigh of relief. The struggle is enormous, but it cannot and should not be fought alone. I hope I can help my patients be empowered in the same way.

Fanon argued we must resist simplicity, mystification, and binaries – lean away from tribalism and into the work of social and political consciousness. This requires facing our terror and shame. My own disgust and anger with the world makes me want to retreat, to think in black-and-white absolutes. Instead, I must sit with the discomfort of complexity. Fanon stated: ‘There are not dogmatic formulas; we must embrace “intellectual elaboration”.’ For my patients, I can validate their anger and fear, encourage self-compassion, and help them tolerate discomfort. I can suggest that they look outward as well as inward. I can remind them that each person must associate themselves ‘’with the whole of the nation [..] to incarnate the continuous dialectical truth of the nation.”

Fanon’s perspective has given me new energy. The world has expanded around me; beyond my own head, beyond the individual therapy space. I can understand more about the person sitting before me as well as the world outside the therapy session, the dialectic between us and all of them. We have to see the sociogenic context of events to understand what is imposed on us all; what dehumanises us and isolates us.

We need to face our shame together, resist self-interest, fight for our rights, and allow sticky complexity. Together, we collectively broaden our awareness, our power, constantly re-examine ourselves, and break the delusions of the oppressors.

© Zebib K. Abraham

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.