Mother Mary Comes to Me

Arundhati Roy

Penguin, 2025

Arundhati Roy has long insisted on the right to be improper, unassimilable, even disreputable. Her first work of memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me, is most alive when it sustains this commitment to irreverence and resistance to self-justification. Anticipating the potential conflict between this stance and the softening demands of the form, Roy writes: ‘I have thought of my own life as a footnote to the things that really matter. Never tragic, often hilarious. Or perhaps this is the lie I tell myself. […] Perhaps what I am about to write is a betrayal of my younger self by the person I have become.’

Steeped in enthusiasm and reverence for Roy, who is an icon in my world: quoted at weddings, gifted at graduations, it feels almost sacrilegious to be left secretly wanting by this record of her remarkable life. Whilst I eagerly, and perhaps somewhat voyeuristically, looked forward to a ferociously honest reckoning – applying the unsparing clarity of Roy’s political writings and the emotional acuity of her fiction to the various conjunctures of her own life – the actual work is far more measured, light, and conciliatory.

As I realised, or had to have pointed out to me, with a hilariously disorienting jolt, ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’ is not some evocative phrase from the Bible but (obviously) a famous line from the Beatles’ ‘Let It Be’. Absurd, of course, to have missed this glaring reference but then again, who would expect such straightforward homage from an iconoclast and self-confessed sceptic like Roy? The title combines the book’s central concern with Roy’s mother, Mary, with the jouissance of the soundtrack to her youth – Roy recalls Beatles songs and ‘Ruby Tuesday’ ringing around her head and ‘humming in her bone marrow’ as a kind protective shield on visits back into her mother’s stifling sphere of control. Yet it also feels paradigmatic of the book’s lapses into the sentimental, which struggle against its more exciting twin pole: a tendency towards irreverence and deconstruction.

The sections where this latter impulse wins out are thrilling. In contrast to the activists she encountered during her reporting on the Narmada valley and the Sarder Sarovar Dam in the early 2000s, she writes: ‘My brief was different. My commitment was to writing. To being a writer, not a leader or an activist. To do that I could not be weighed down by the burden of a “following”, or of fulfilling people’s expectations. I had to have the right to be unpopular […] I was not a Gandhian. I was a critic. A sceptic’. This attachment to scepticism runs through the book, accompanied by its twin thread: an instinct for self-effacement and self-denial. Like her mother, who decided to ‘shield and safeguard’ the ‘memory of her mortification’ at the hands of her brother and mother (her expulsion from the family home), ‘as though it were a precious family heirloom’, before recasting it as her landmark overthrowing of the Travancore Succession Act, Roy has learnt to transmute the traumatic experiences of her childhood – when she felt herself ‘shrinking from [her] own skin and draining away, swirling like water down a sink until [she] was gone’ – into a feeling of ease with discomfort and an indefatigable self-possession.

Roy’s childhood planted the seeds of resistance to coercive discipline, which ultimately motivated her to up and leave home at sixteen and which instilled her with the audacity needed to take on the establishment throughout her career, facing several court cases, an infinity of obscene threats, and a night in prison. Similarly, the choices she has made in her personal life – repeatedly turning away from otherwise happy marital domesticity – are described as propelled by the ‘cold moth’ on the heart: the emotional legacy of her unpredictable mother. ‘The price I paid for being Mother Mary’s daughter and the writer that I am,’ she concludes, ‘was not prison or persecution (although there was some of that, too). It was catastrophic heartbreak.’

There is a perversity in this economy of love and damage that I find deeply compelling – a twisted logic where self-preservation demands self-annihilation (the ultimate figure of which is the twins’ incestuous, sorrowful lovemaking at the end of The God of Small Things) – but which is sanitised a little too quickly here by the memoir’s gravitational pull toward reconciliation and legibility. Roy’s power has always resided in deployments of both clarity and mystery: her political essays are searingly transparent, whereas her fiction thrives in the lush acceptance of opacity. This memoir, caught between these modes, sometimes settles for a surface-level confession that betrays the deeper, more difficult truth.

Roy is, as she writes, a master of ‘the exquisite art of failure’ – a lesson taught by her uncle, G. Isaac (Chacko in The God of Small Things), who memorably promised the six-year-old Roy a coveted locket ‘only if you fail’. Yet in this memoir, Roy seems at times to excuse herself from this work. The tenderness and difficulty with which she describes the continual making, unmaking and remaking of all her friendships and relationships calls to mind Gillian Rose’s assertion that ‘to live, to love, is to be failed; to forgive, to have failed, to be forgiven, for ever and ever’. However, it seems that she underestimates both her readers and herself when she writes: ‘in the pages that follow it might be confusing for readers who are searching for conventional declarations of love, coupledom, marriage, divorce, separation and love affairs to understand how I lived (live) my life. I often don’t understand it myself. I have stopped trying.’ Whilst this sentiment is disarming, it also feels like pre-emptive surrender. Would it not be truer to fail trying?

There is something un-Arundhati about memoir, a form which sits uneasily with her discomfort with the hard, exclusionary borders of the nation-state, the nuclear family, the sovereign individual. I wish she might have stuck more closely to the struggle of inhabiting that contradiction itself, for it feels like Roy has reached too soon for a compromise.

Penguin Random House: Mother Mary Comes to Me

Miraya McCoy

Miraya McCoy lives in London and works as an editorial assistant on Bloomsbury’s philosophy list.

Granta 173: India

A look at four short pieces of fiction from Granta's latest edition showcasing Indian writing

The Thing with Feathers

Dylan Southern’s film adaptation puts masculinity front and centre

It Was Just an Accident

Iranian director Jafar Panahi's film probes the relationship between individuals, the state and violence with determined humanism

Other Wild

Emily Zobel Marshall invites us to heal by connecting to our senses and the natural world

Fiction Prescriptions

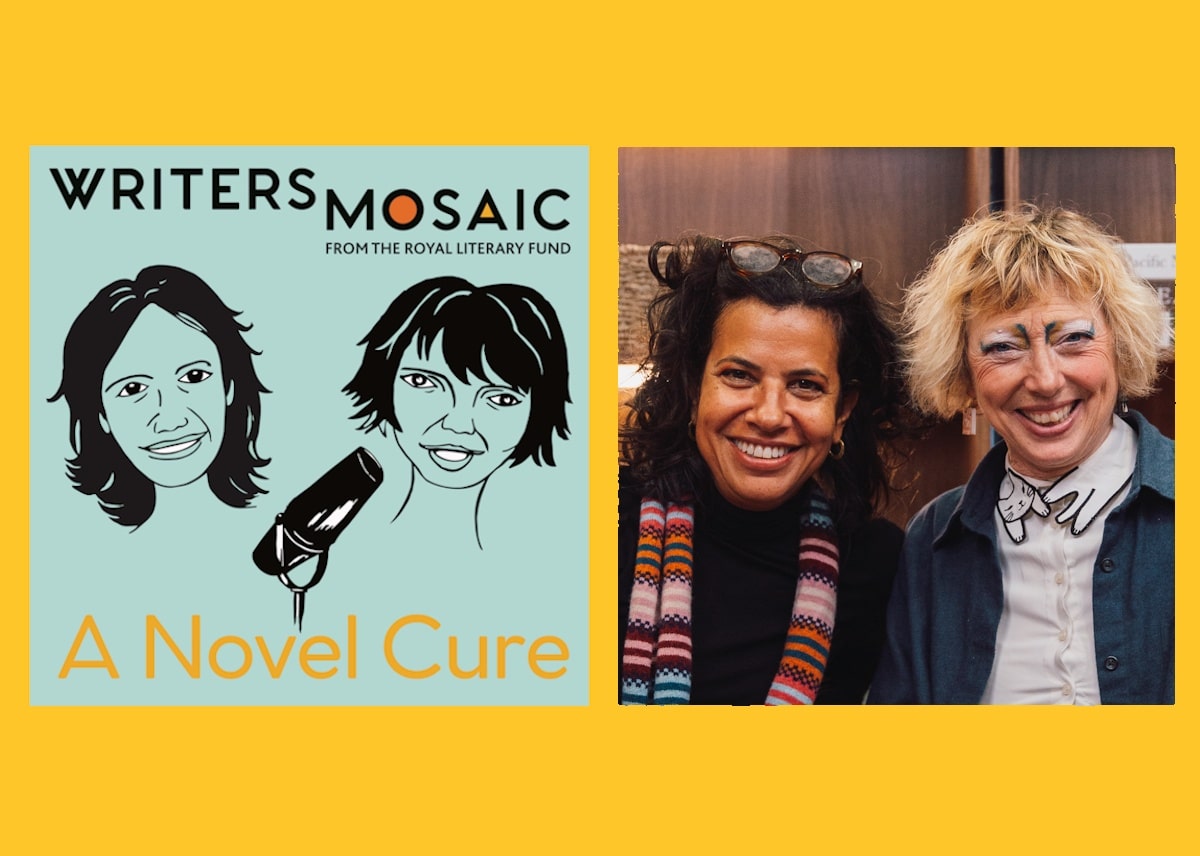

Co-hosts Ella Berthoud and Isabelle Dupuy introduce our new podcast series, Fiction Prescriptions: A Novel Cure, focussed on bibliotherapy. Each month listeners can write in with their dilemmas, and our dynamic duo will suggest remedies for the head and heart, drawn from books.

All the men my mother never married

A chapter from an unpublished autobiography, dedicated to my mother, Sarah Efeti Kange

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Afro-Caribbean writer Frantz Fanon, his work as a psychiatrist and commitment to independence movements.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube