Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Alternative destinies

In their last year of secondary school, two Haitian students were selected to participate in a French essay competition in Martinique. They flew together from Port-au-Prince and gaped at the French flag flapping under the familiar sun. They noted the thin and white licence plates, the good roads, and the Carrefour store with a flamboyant tree in front. They were standing in an alternate universe – one in which the colony persisted. After a while, one of the students kissed his teeth. ‘Bah,’ he lashed out, ‘Land of welfare recipients.’

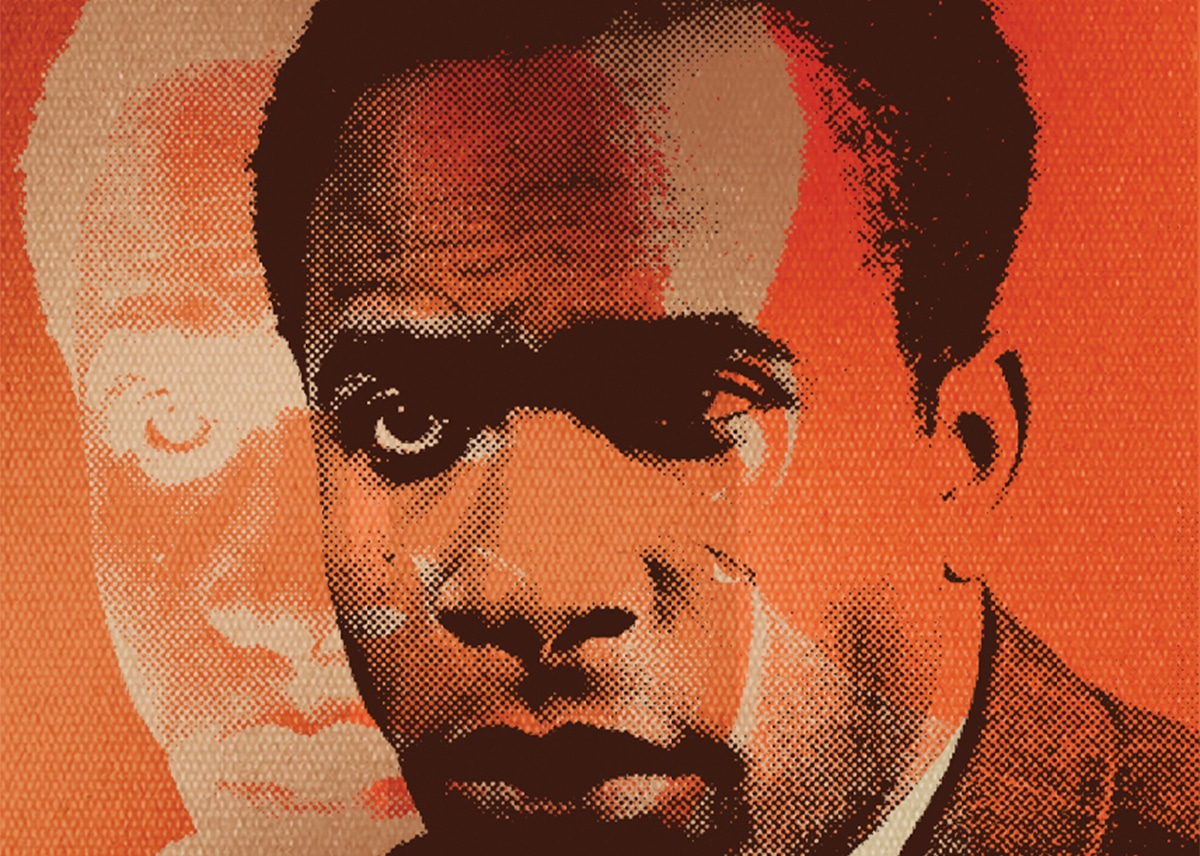

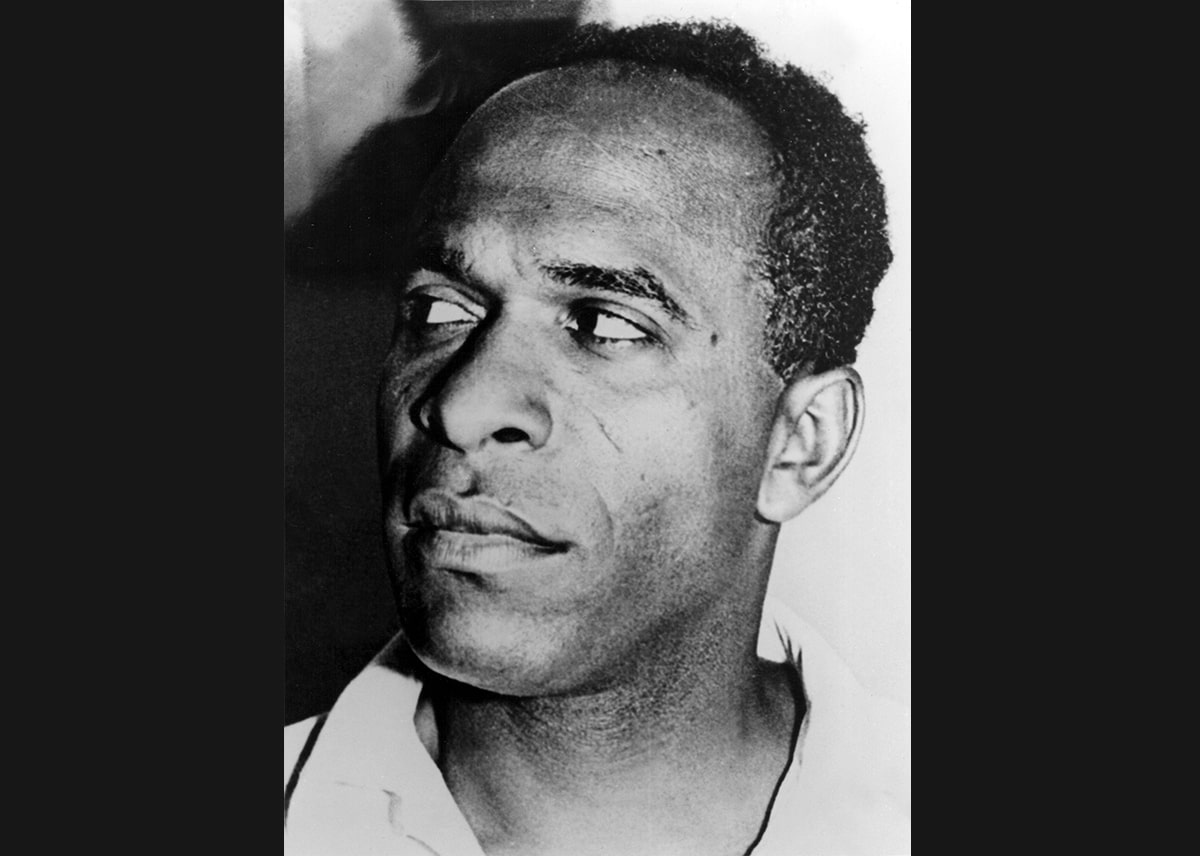

Here is the paradox at the heart of Frantz Fanon’s life and work. Fanon (1925-1961) was a Martinican psychiatrist who became a pivotal figure in the Algerian War of Independence. In Fanon’s eyes, the Martinican man, unlike the Haitian, carries the additional burden of having allowed the master to free him. Fanon grew up walking past the statue of the white abolitionist Victor Schoelcher on his way to school. The Haitian, by contrast, fought for his liberty and prevailed, and has been punished by the colonial powers. Nevertheless, Haitians, no matter how poor or wretched, carry their victory in the marrow of their bones.

The pupil’s harsh outburst concealed his sadness. People in Martinique live a hundred times better than people in Haiti or Algeria. Frantz Fanon became a psychiatrist in 1951 after serving with De Gaulle’s liberation forces, not because his family could afford medical school, but because he was French. His first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), is the beginning of his exploration of power and race. He is a Black man ‘in and of his time’, yet he is an outsider, unable to escape the colour of his skin and unwilling to accept either of the options the whites offer him: ‘erasure’ or inferiority. Fanon’s writing is full of the cadences, humour, and wit of his island. His accent rises from the page. Jokes about ‘rolling the Rs’ in French, or about the snobbery of those who’d seen Paris and forgotten their Creole, are familiar. When he writes about the tragedy of Mayotte Capécia, a Black Martinican obsessed with marrying a white man, an uncomfortable truth emerges. Haitian writer Cléante Valcin had written an eerily similar story in 1933 called ‘La Negresse Blanche’.

Black Skin, White Masks turns out to be as relevant to the Haitian psyche as to the Martinican’s. Somehow, the Haitians, after finding the courage to eliminate the French, settled into the same kind of colonial complexes as those denounced by Fanon.

Where are the fruits of the Haitian Revolution? In The Wretched of the Earth (1961), Fanon provides a call and a method for the oppressed to kick out their European colonists. It follows the Haitian strategy of the time. Because all exploited people have been subjugated violently, it is only with a rifle that the ‘peasant’ can become a man again – through killing the settler. ‘Violence hoists the people up to the level of the leader.’

Jean-Paul Sartre is scathing in his judgment of Europe in his introduction to The Wretched of the Earth. He calls for the violent end of their empires: ‘To shoot down a European is to kill two birds with one stone […] There remains a dead man and a free man.’ As a European, however, Sartre does not write about what happens after liberation. He cannot imagine societies that have forgotten how to function. Fanon, though more nuanced, also struggles to formulate a postcolonial future not defined by European thinking. There is only one possible answer for him: Marxism. Anything else will be perverted by a local bourgeoisie that will wear the ‘mask’ of the coloniser. Fanon calls himself an Algerian. He embraces the FLN as the surrogate movement that did not happen in Martinique. Yet, for all his identification with the Algerians, Fanon never learns to speak Arabic. He idealises the Algerian peasant but knows little about Berber culture or Islam.

Fanon died in 1961, one year before Algeria declared independence. He was spared the sorrow of seeing his idealistic dream reduced to a totalitarian Islamist state. Three decades later, Algeria was still struggling with a civil war so brutal that its massacres echoed the colonial atrocities Fanon had condemned. The rifle won sovereignty; it could not guarantee a plural republic.

A century after Fanon’s birth, the structural facts he named persist. Supply chains still consign the South to exporting raw commodities while the North refines; armoured vehicles idle outside tenements from Caracas to Gaza. Just like the Haitians, the Martinicans bled for France in cane fields and slave holds. Haven’t they suffered enough to claim the benefits of a state enriched by their blood and tears? Now a French passport delivers paved roads, pensions, and first-rate clinics – comfort that to many looks less like capitulation and more like an overdue dividend on centuries of exploitation. Yet most Haitians, made equal through violence, still speak of fighting against life instead of living it. They are terrorised and impoverished by gang warfare. How many Haitians and Algerians would happily trade places with a Martinican? Thirty years ago, in spite of their youth and patriotism, one of the students’ answers was already unclear. Fanon yearned for the dignity of those who had freed themselves. He could not have imagined the price the people would pay for their successful revolutions.

© Isabelle Dupuy and Zoe Mohaupt

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.