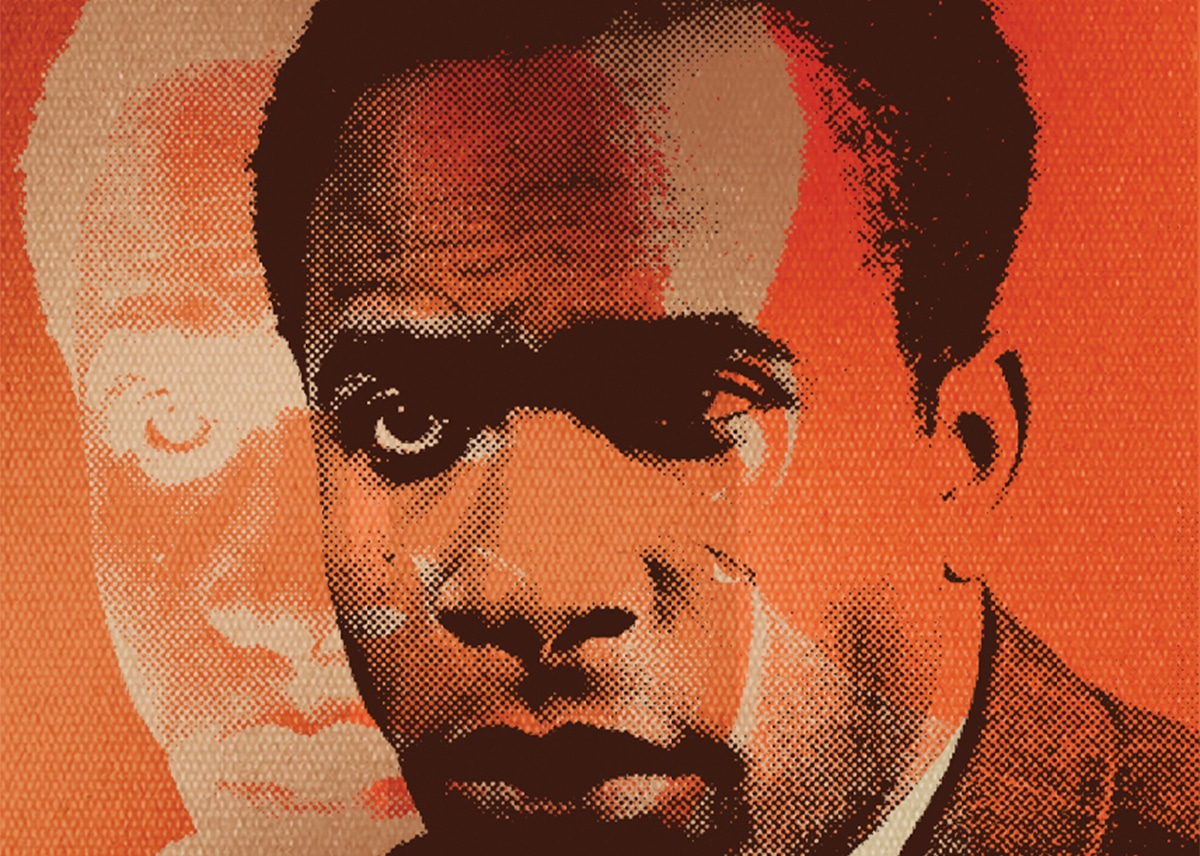

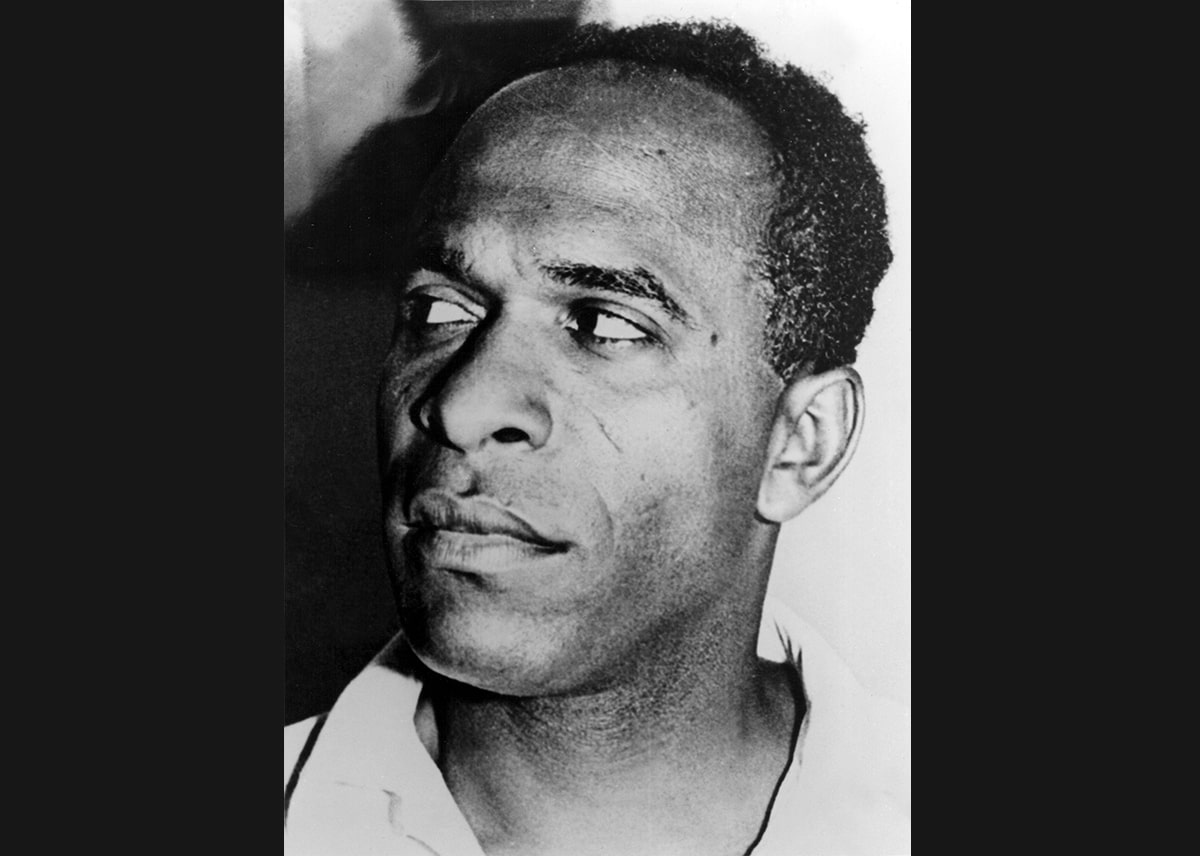

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Today you make a new attempt at group therapy. To create a sense of occasion, you cover the table in the big refectory with a white cloth and place a vase of flowers at each end. Azoulay and Lacaton sit beside you, along with another young, progressively-minded intern, Charles Géronimi. The men shuffle in, not looking up as they take their seats.

You try to rouse their spirits. This hospital can be a place of equality where the sick and the well work together to create a world even better than the one outside, you say. That is why the liberation of patients is not just a matter of individual treatment. The structures that surround you men – the hospital itself – must be reformed. Not just the old practices of restraining and locking up patients, but also the regimes of forced idleness and numbing routine. Your days here must evoke the texture of everyday life. Slowly, hand in hand with the doctors and nurses, you can become your full selves again.

When you finish speaking, the men stare blankly back at you. One patient yawns noisily, scratches his stubbly chin, then slouches off to the courtyard. The only one of them who seems to be paying attention is a middle-aged man, a former customs official and notorious bore, who launches into a long monologue in French – chiefly, it seems, to make it known he’s ‘made of better stuff’ than the others. The whole session was nothing more than an empty exercise, you complain to Lacaton afterwards. Absurd. Devoid of meaning. An embarrassment.

Your fellow doctors watch your efforts with amusement. Ramée takes you aside one afternoon to offer his advice: ‘When you’ve been in Algeria as long as I have, you’ll understand how futile it is to expect anything from Muslims. They are simply too undeveloped in their thinking to ever change.’ Behind your back, says Azoulay, the other physicians call you the ‘Arab Doctor’.

You know they are mocking more than your sympathy for the men in the hospital. To your colleagues, there’s no fundamental difference between you and your patients. If you’re not European it’s all the same to them, whether you’re Arab or West Indian. The first time you understood that this was how such people thought was when you arrived from Martinique to study in Lyon. It was an ugly realisation. There were some 20 students from West Africa at the university, while you were the only one from the Caribbean. At home you’d been brought up believing in Martinique as a district of France, seeing yourself as a child of the home nation, rather than belonging to the colonies like a Malian or a Senegalese. It turned out your white classmates made no such distinction.

You were even taken for an African at a party near Place Guichard, the old town with its narrow, dark buildings, the student district. A girl called to you from the other side of a crowded room, ‘Omar, Omar!’ She rushed over to you and then, realising her mistake, dropped your arm, saying, ‘I’m sorry, I thought you were Omar Traoré.’ She smiled and you smiled, and you both agreed it was an unfortunate error. Except that similar mistakes kept happening, often enough that you were forced to understand it as a deliberate refusal to recognise you as the Frenchman you’d been raised to believe that you were. Your friends at the university praised your ‘good French’, as if you hadn’t been speaking it all your life. In the next breath they told you they didn’t ‘see’ colour. Once, during a class, you made an observation about the connection between Caribbean and European poetry that won the praise of the professor. As you filed out of the lecture hall, one of those friends patted you on the back. ‘Well done, Fanon, at heart you’re basically a white man.’

You have been invited to witness another exorcism. Although Lacaton arranged the visit, he is away from the hospital at present, Azoulay too, so it’s just you walking up into the foothills through the afternoon. It is dark by the time you arrive. A group of villagers are sitting in a circle around two women lying on the ground, their faces illuminated by a fire, rapt and grave. The village marabout kneels over their supine bodies, chanting and singing while they struggle and fit. Sometimes the onlooking villagers join, raising their voices to accompany the marabout. At other moments, the only sound is the crackle of the fire, the popping of logs. The ritual continues into the night until your hands and feet tingle with cold. Eventually you wander out to the edge of the village. In the perfect blackness you can see nothing before, or below, you. Just the constellations above are visible, hard and bright, the stillness of the tableau interrupted only by the forlorn grace of a shooting star in descent.

By the time you return to the fire the two women are gone, but the villagers are still gathered around, singing now and ululating and dancing. Against the backdrop of the silent mountains, this coming together of music and bodies feels like its own kind of exorcism, a collective conjuring away of the forces, whether social or supernatural, that might haunt each villager, and an affirmation perhaps of the bonds that unite them. Later, when you read them back, you’re struck by the delirious quality of the notes you made that night. ‘There are no limits inside the circle. The hillock up which you have toiled as if to be nearer to the moon; the riverbank down which you slip as if to show the connection between the dance and ablutions, cleansing and purification – these are sacred places. There are no limits – for in reality your purpose in coming together is to allow the accumulated libido, the hampered aggressivity, to dissolve as in a volcanic eruption. The evil humours are undammed, and flow away with a din as of molten lava. When they set out, the men and women were impatient, stamping their feet in a state of nervous excitement; when they return, peace has been restored to the village; it is once more calm and unmoved.

You are still thinking of the villagers days later. It occurs to you that perhaps the reason you haven’t got through to your patients is because you’ve been trying to introduce activities based on a European, Christian worldview. What does a film like Daughter of the Sands, with its caricatured depiction of Arab nomads and princesses, mean to men who know the real desert? Come to that, why expect them to contribute to Our Journal, when, as it transpires, most of them can’t read or write? You have insisted on the sovereignty of Western values. These colonial delusions are hard to shake off. It is so easy to become the coloniser yourself.

© Ekow Eshun

Ekow Eshun

Ekow Eshun is a writer, curator and broadcaster whose work stretches the span of identity, style, masculinity, art, and culture.

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.