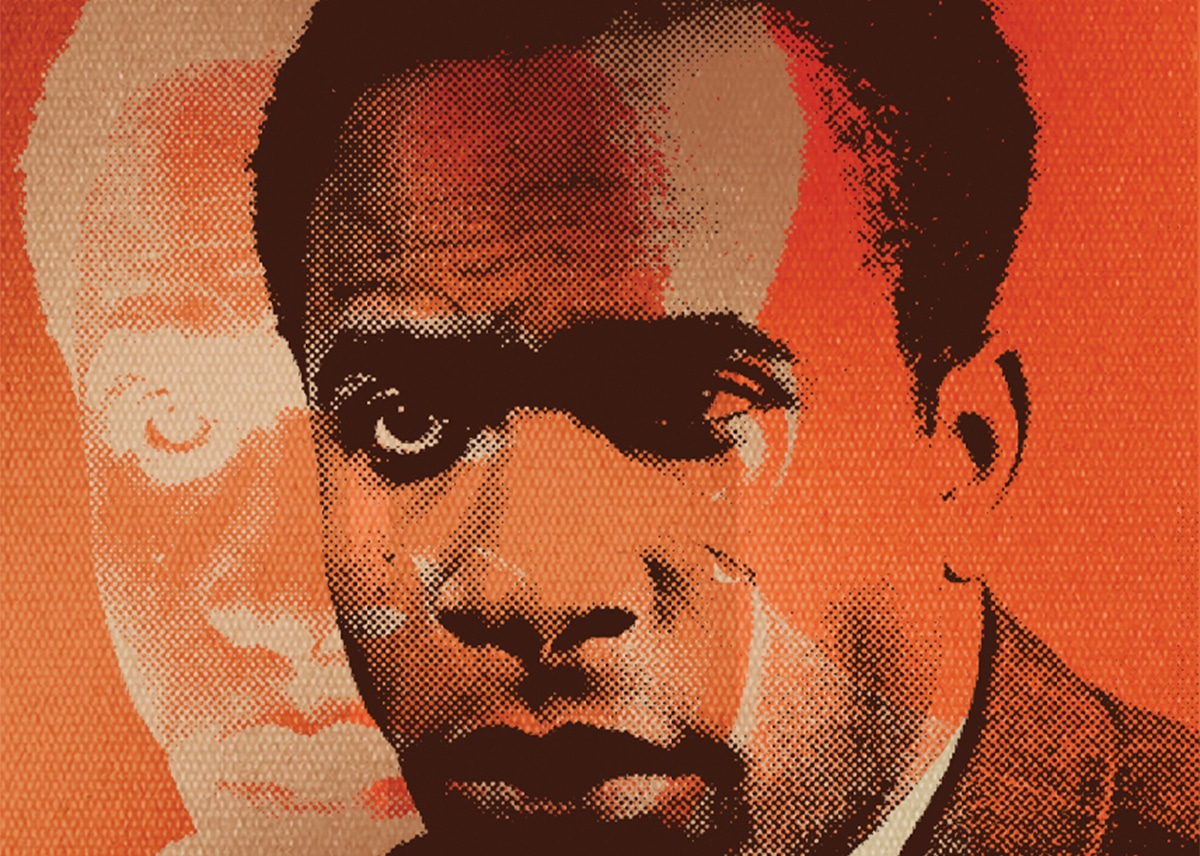

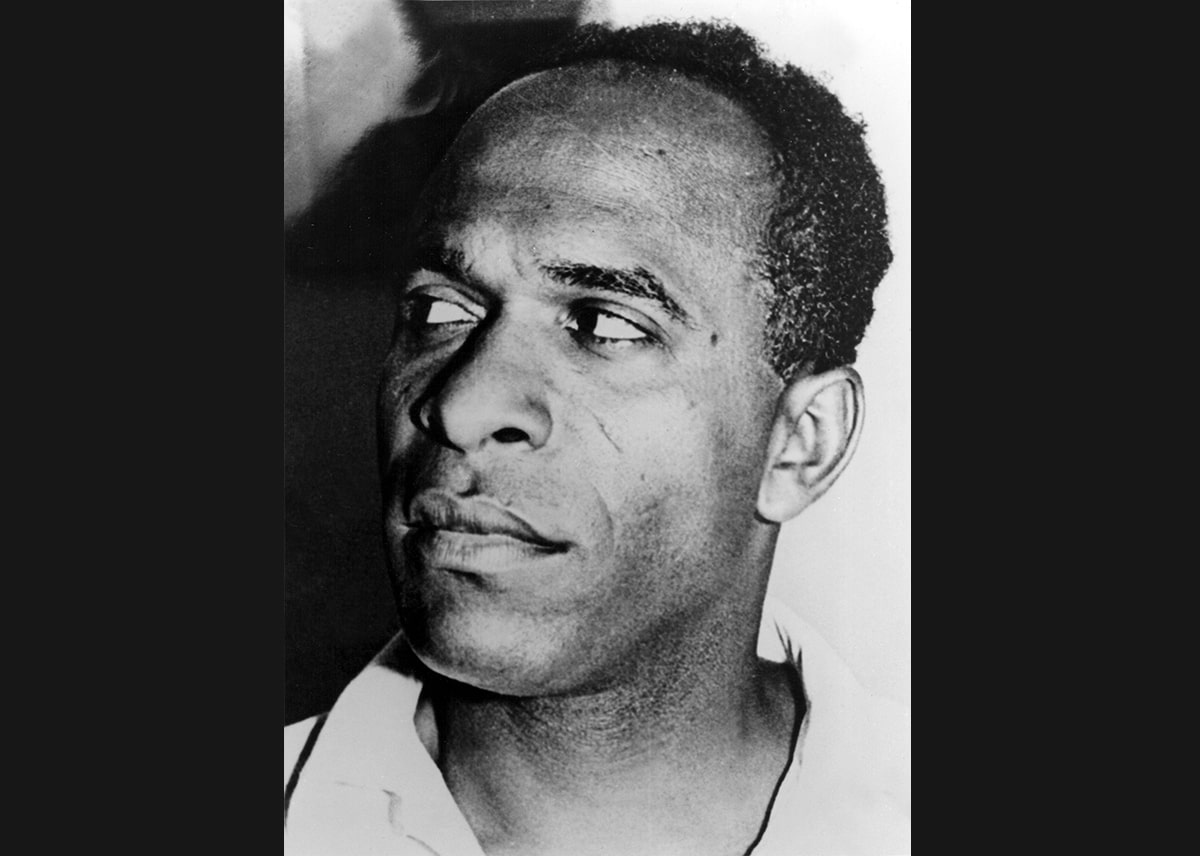

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Brown skin, white mask

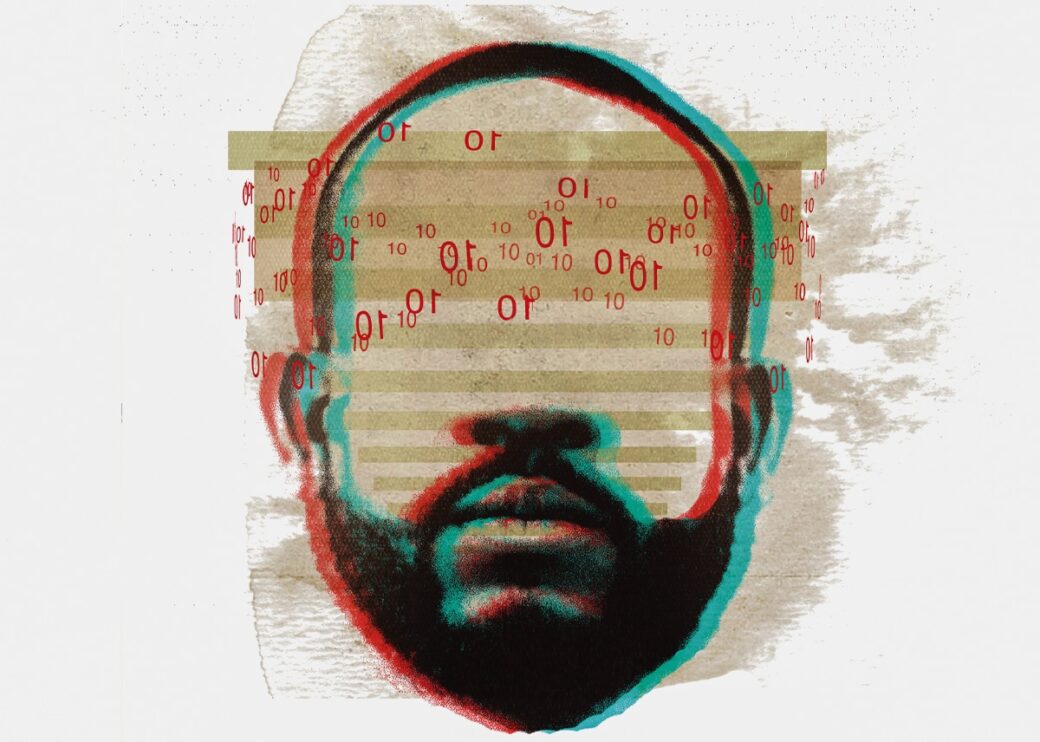

My parents wanted me to become a doctor. They were conscious of the need to survive as a minority – something I didn’t understand when I was young. Frantz Fanon wrote The Wretched of the Earth in 1961, the very same year my father arrived in London from Pakistan. They were both born as colonial subjects who travelled to the imperial centre. For me, reading Fanon today is as incendiary as ever. He exposes my own ‘white mask’ – a mask erasing my origins that might make me complicit in racist structures.

As an NHS psychiatrist, it could not be clearer to me that racism causes mental illness. I work in an inner-city area where the majority are non-white. COVID-19 showed the vulnerabilities of minorities in Britain. Black people were four times more likely to die in the pandemic. Also, if you are black, you are much more prone to a severe mental illness like psychosis – and then more likely to have forced treatment under a section. The system puts a white mask on me: I am the one sectioning patients.

A friend of mine is part of the all-white, all-male leadership of an organisation. When faced with a race issue, he turned to me. His employee had thrown a hand grenade when she left her job, saying that the organisation was ‘toxic, white and male’. My friend didn’t know what to do. A few weeks later, I asked what had happened next. He said that they now have ‘race’ as a recurring item on their monthly meeting agendas. This is why Fanon is relevant for me today. When Fanon sees oppression, he picks up arms. But in our organisations, when we see structural racism, we bury the issue in an agenda item.

At my senior clinical management meeting, the issue came up again of why ethnic minorities, particularly black people, are more likely to end up in the psychiatric intensive care unit. There was a call to join a committee to look into this. My impulse was to put my hand up to volunteer, but I didn’t. At that point, I felt frustrated and demoralised that the inequalities I first heard about as a medical student are still operating.

In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon writes, ‘Decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon.’ During the Black Lives Matter protests, the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston was thrown into Bristol Harbour. It was a visceral and symbolic moment that I am completely behind. But I also agree with David Olusoga, who writes that ‘you can topple Colston, but how do you topple racism?’’ There is a disconnect between the singular action that happened in Bristol and the hard-to-grasp task of unravelling racial inequalities and injustice.

Fanon talks about the ‘dependency complex of the colonised’. Ninety years later, I know that something like this still operates. I monitor what I say depending on what setting I am in. An awareness of my identity as perceived by others modulates my speech. A friend of mine of similar background to me is a politician. She wears a light red cotton scarf to represent her support for Palestine, although nobody would know what it represents apart from herself – because publicly she chooses to remain silent about what is happening.

I envy Fanon. His position is an immediate and unambiguous call to arms. My options are perhaps to join or not join committees, to boycott or protest. He shows through his words and his life a point of no return – of realising his position in a structure, identifying with the oppressed, and making that the starting point of resistance. This is a process of radicalisation, of seeing, and of coming into consciousness.

I can now see the two elements in me that are in opposition to each other. I have the white mask that is my institutional self. This is opposed by my radical/radicalised self that cannot unsee the exposed structures around us. My agency is caught somewhere in between.

© Khaldoom Ahmed

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.