Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Inglan mad dem

‘Why are black people six times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than their white compatriots?’ asked Professor Walvin. It was 1981, and that year there were only two identifiably black students among the intake of The London Hospital Medical School: Amaju Ikomi, a foreign student from Nigeria, and me.

Walvin stood at the lectern. His eyes ranged across the auditorium and stopped at me. He waited. I was flushed with embarrassment. ‘Mr Grant, would you care to hazard a guess?’ When it became apparent that I would not be drawn on the subject, Walvin answered for me, averting his gaze and addressing the body of students. ‘Black people suffer a higher incidence of schizophrenia because black people are schooled in paranoia.’ I was affronted by his assertion, but I said nothing.

Had I read Black Skin, White Masks, I might have recognised that, from Frantz Fanon’s perspective, Walvin was practising what the psychiatrist called ‘the racial allocation of guilt’. Fanon referred explicitly to the spectre of black soldiers subjugating rebellions at the behest of their French overlords, but the notion speaks generally to the way, writes Fanon, that enslavers and colonisers recruited ‘‘peoples of colour’ who annihilated the attempts at liberation by other ‘peoples of colour’.’ During the period of the Atlantic Slave Trade, for example, the black slave driver did his master’s bidding in whipping the enslaved. Walvin’s assessment boiled down to the idea that, in the generations after abolition and colonialism, black intermediaries – equivalent to drivers – had wielded the whip of paranoia over their brethren. Walvin had neatly absolved descendants of colonisers of their part in the mental ill-health of my black British peers.

A decade earlier, I recall there had been numerous stories in Luton, where I grew up, of troubled Jamaican youngsters being sent by their parents back to the Caribbean. When I asked my mum, Ethlyn, what was going on, she answered dryly, ‘Inglan mad dem’. Ethlyn’s sad observation came to mind later at medical school whenever I was assigned the task of looking after the pitiful black patients on psychiatric wards.

I imagine Fanon would have reached the same conclusion as my mum about the assault on the mental health of the formerly colonised and their descendants in hostile environments – whether in Luton or Algiers, where Fanon practised.

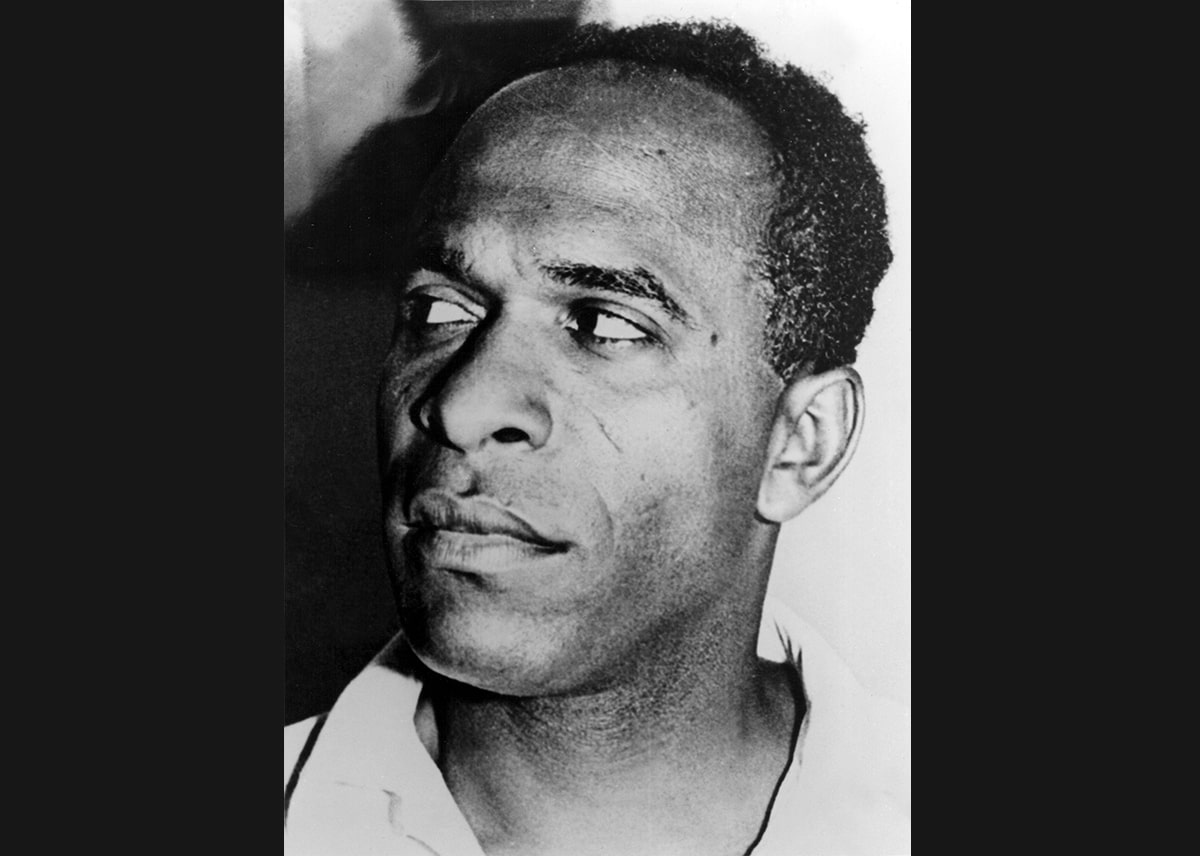

‘In psychiatry,’ argues Fanon, ‘there are latent forms of psychosis that become evident following a traumatic experience.’ Fanon died in 1961. He never used the phrase generational trauma, which only started gaining traction among psychologists in the mid-60s, but its notion haunts the pages of his first book, Black Skin, White Masks, published in 1952.

Fanon’s book has a youthful, searching urgency to it; he was 27 and had only recently completed his training at medical school. Frequently, it reads like a literature review of different types of texts – academic research as well as novels – especially those with an autobiographical slant that offer up case studies.

The purpose of Black Skin, White Masks, writes Fanon, is ‘to enable the colored man to understand by way of clear-cut examples of psychological elements that can alienate his black counterparts.’ I’d argue that Fanon recruits himself as a case study for his thesis – an inquiry into the inner life of an intellectual and traumatised black man who shuttles between the white and black world as a proxy for an ‘abandonment neurotic’ who must make a choice about where his allegiance lies. That conundrum later resulted in Fanon electing to become a participating observer, siding with Algerian rebels in their violent fight for independence from France – a decision which challenged a core principle of medicine: first, do no harm.

Fanon’s use of ‘we’ throughout Black Skin, White Masks is at first unsettlingly academic and distancing until his sincerity and generosity becomes clear, at which point his empathy is also apparent. The book is particularly insightful in its interrogation of strategies for neutralising the impact of the hierarchical racial code (an ‘epidermal racial schema’) introduced by colonisers as a construction of racism.

I wish I’d been introduced to Fanon’s study 40 years ago at medical school; it would have helped to skewer the fallacy that black people had brought psychological misery upon themselves by schooling each other in paranoia.

A version of this feature was first published on 10 August, 2025 in The Observer.

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

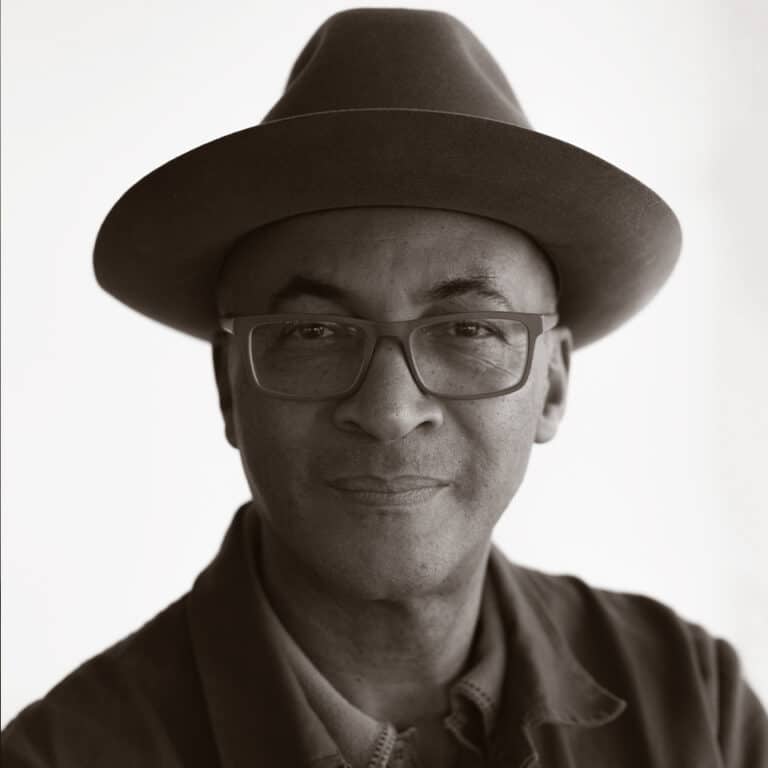

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.