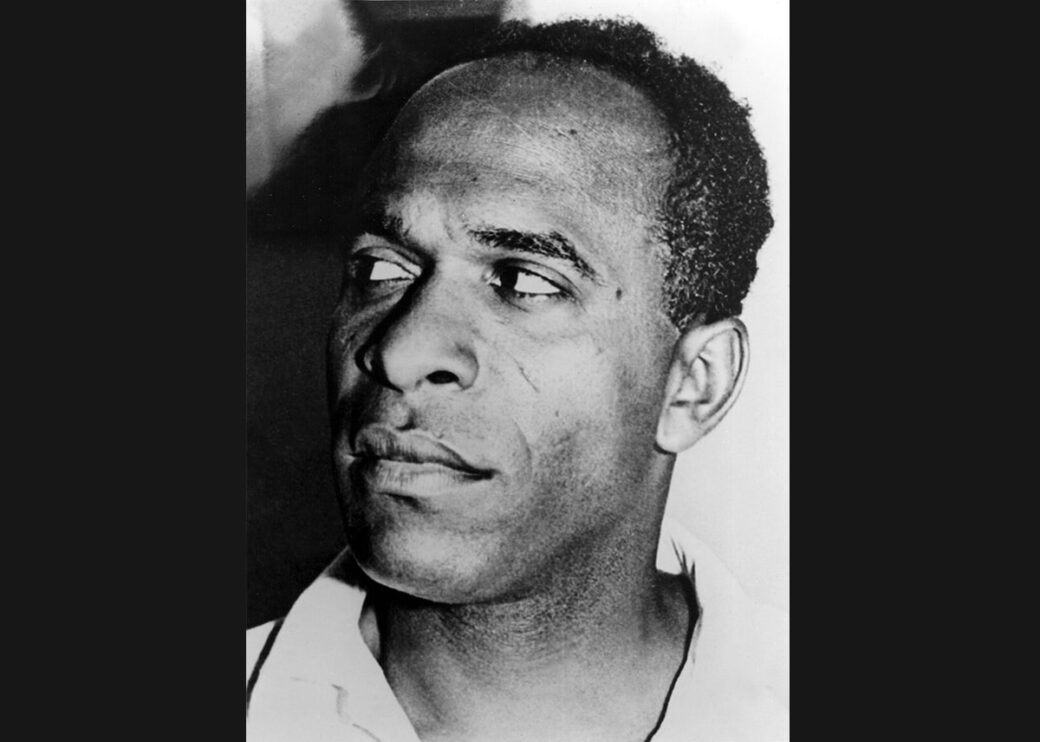

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

On entering the zone of being

Allow me to introduce you to two people. One is the man from Martinique, born in one of France’s ‘vieilles colonies’ in the summer of 1925. A man of many masks: some imposed, some acquired, others seized for himself. Black Frenchman, soldier in the French army, West Indian medical student, non-Muslim revolutionary in the Algerian resistance, African, philosopher, poet, doctor, and psychiatrist. The other is a British-Indian woman from peaceful, affluent, southwest London, born in the spring of 1979 or, as it will come to be known, the winter of discontent. What could this man possibly have to say to this woman? Nothing, surely. There is no overlap between their lives, races, experiences, or time on this earth.

And yet.

He speaks to me.

‘When people like me they tell me it is in spite of my colour.’ Those unbearably on-the-nose words, written by Frantz Fanon in France nearly 30 years before I was born, when he was not yet 30 himself, so accurately describe my own life they take the breath from my body.

I grew up in Richmond-upon-Thames, at least until our house was repossessed in another (not unrelated) winter of discontent. And while it’s true that some of my friends’ parents in this immaculately preserved swathe of British imperial history were professors, doctors, and psychiatrists, none, as far as I know, kept a copy of Black Skin, White Masks by their bedside. And if I had heard about Fanon then, he would probably have been traduced as an apologist for terrorism. As for my parents, they were born under the British Raj and came of age around the time Fanon’s anti-colonial ideas were setting the newly independent India alight. But they never mentioned him – nor, for that matter, did they talk much about the mother country. As for me, all my friends (and foes!) were white, and assimilation was the only option. At Glasgow University in the 1990s, I studied philosophy. In the political module there was Marx, Mill, Hume and, in the modern continental module, plenty of Sartre, Foucault and, looming behind them all, Freud – but no Marxist existentialist from Martinique.

I did not find Fanon when I most needed him. Which is to say, for the entirety of my childhood and youth, too much of which was spent – to borrow one of Fanon’s most grimly evocative and famous phrases – in ‘a zone of non-being’. In this zone, white people of all ages and persuasions would squeeze my skinny brown arm whilst saying, with genuine pity or – worse – affection in their eyes, but not you. It was ‘when people like me they tell me it is in spite of my colour’, all over again.

Fanon found himself in the zone when he left Martinique a French subject and alighted in Lyon and Paris a black object. His hurt and incensed response to the brutal shock of being racialised for the first time touch me deeply, no doubt because there were no such shocks for me. It is a necessary condition of the second generation, born as we are into a country that deems us strangers, to know no different.

I’m a writer – like Fanon and all the others who have been othered – preoccupied with trying to find the most befitting and beguiling language to illuminate experiences for which, away from the controlled environment of the blank page, there are no words. Sometimes, though, a little wish-fulfilment creeps in. I wish I’d had a profound, lifelong relationship with Black Skin, White Masks, but I have not. My political thinking was not shaped by The Wretched Of The Earth. I read Fanon properly – in his own words rather than all the ones written about him, which is very much not the same thing when it comes to Fanon – for the first time in my early forties, which is the decade I’m still in. I’m ashamed to write this until I remember those incantatory words: ‘Shame. Shame and self-contempt. Nausea.’ The racialised psyche, Fanon reminds us again and again, has nowhere to turn but upon itself. ‘I have a phrase for this,’ he writes helpfully in Black Skin, White Masks: ‘the racial allocation of guilt.’

‘I honestly think it’s time some things were said,’ he notes in that book’s incandescent introduction. Thank god, he said them – and in the most rousing and oblique prose. People say Fanon is hard to read, but I love the way his words flash, tremble, and haunt like crazy weather. His writing is as resistant as his politics, which is surely the point. ‘Only some of you will guess how difficult it was to write this book,’ he writes. And some of us do. He never sat at a typewriter or wrote with a pen, which is unsurprising considering all he got done in his brief, tumultuous, urgently lived life. Instead, he dictated his prose, pacing up and down – and that’s exactly how it reads. The sentences keen with frustration, unspent rage, bursts of clarity, and hope.

Lived experience.

White gaze.

Man of colour.

Woman of colour.

All are terms Fanon was using in the early 1950s, though, of course, I wish he had used ‘woman’ more, and more humanely. Still, I love the way his sentences pile up, demanding we get on with the impossible business of decolonising our minds. No one was talking like this in 1980s Richmond-upon-Thames, just as they weren’t talking about it in Lyon and Paris when Fanon wrote Black Skin, White Masks. That book explains what happened to me and why, which is when the lifelong work of taking off the white mask really begins.

© Chitra Ramaswamy

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.