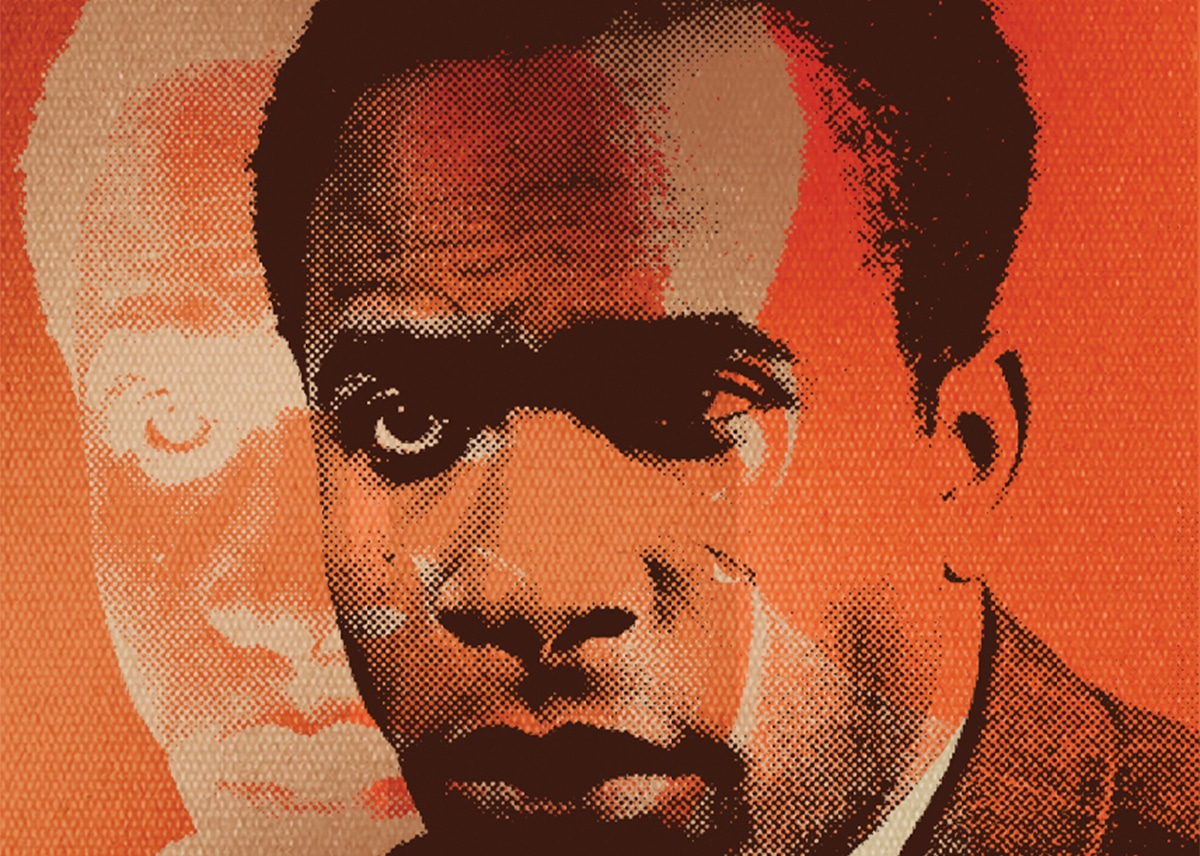

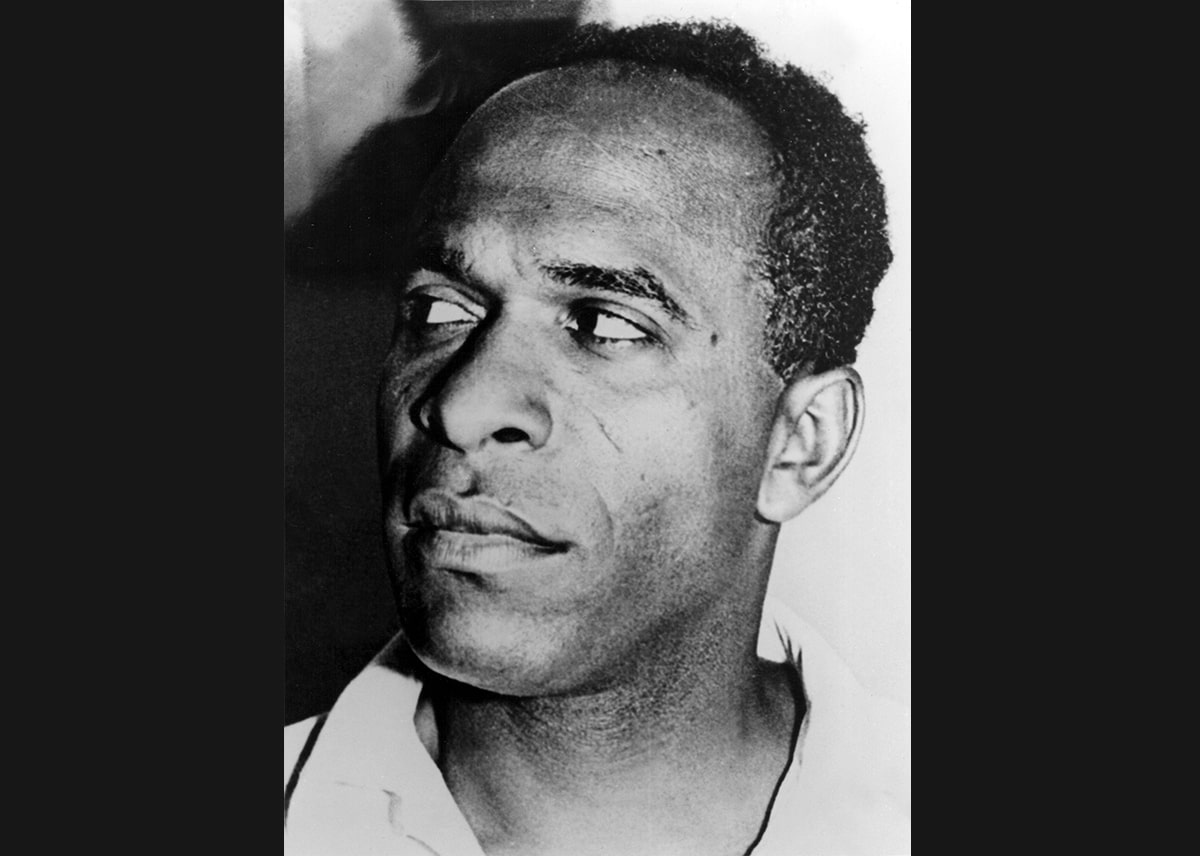

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

The person and the nation

I first read Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks in the summer of 2017, through the lens of the Black Lives Matter movement, which mobilised each time a black person in America died at the hands of police or a white civilian. I wished Black Skin, White Masks had been placed in my hands at 15 as part of a library of consciousness that might have helped better prepare me for life encased in a black, male body.

At 35, I was undergoing a process (that continues) of unravelling an education that did not centre my subjectivity. I realised that black is a qualifier, like gay or poor, suggesting some kind of compromising modification away from the norm. A man is an able-bodied, heterosexual, cisgender white man, whose subjectivity is unquestioned. A man is expected to thrive regardless of whatever misfortune he might encounter; to fail upwards. This world is not set up for me as an individual to thrive in unless I follow a path dictated by my race, class, gender and faith. I contribute to a capitalist effort centring white patriarchy, which it is impossible to be fully liberated from, so the freedom I assumed I had was an illusion. Fanon says that ‘for the black man there is only one destiny. And it is white.’ But I didn’t know any of this at 15. It was never put to me that ‘the black man is a black man; that is, as the result of a series of aberrations of affect, he is rooted at the core of a universe from which he must be extricated.’ I didn’t yet understand my own deep-lying inferiority complex, or the strange, violent, dehumanising things that happened before I was born to people who looked like me.

Rereading Black Skin, White Masks in tandem with Fanon’s final book, The Wretched of the Earth, I see that the latter is more responsible for his legacy as a founding postcolonial theorist. Black Skin, White Masks primarily focuses on creating a ‘new man’ for a new era, while seeking to ‘help the black man to free himself of the arsenal of complexes that has been developed by the colonial environment’. It was a book for Antilleans who saw themselves, and continue to see themselves, as French. The Fanon of Black Skin, White Masks was not looking for Antillean independence or reparations from the mother country, but simply to move forward with a different, more inclusive and universal mindset. ‘I am personally interested in the future of France, in French values, in the French nation. What have I to do with a black empire? ‘ he asks. ‘The authentic grasp of the reality of the Negro could be achieved only to the detriment of the cultural crystallisation.’ This latter point is furthered, but from a decolonial perspective, in The Wretched of the Earth, in which newly independent nations are encouraged to realise their own subjectivity, and to avoid becoming a facsimile of Europe.

Fanon was born and raised in Martinique, which remains an overseas department of France. As an Antillean, Fanon sought to establish a France that was both multi-ethnic and multicultural. While understanding that the national consciousness of the Antilleans is French, he also notes how visitors from the Antilles to France are infantilised: ‘A white man addressing a Negro behaves exactly like an adult with a child and starts smirking, whispering, patronising, cozening.’ He uses the example of how French doctors speak to black patients as opposed to white patients.

Those who would accuse Fanon of hyperbole should know that the Antillean experience in the UK was no different. Consider the case of my paternal grandfather, a labourer who moved to England from Jamaica in 1956 as a healthy, expectant father. Soon after arriving, he began to experience strong headaches, blurred vision, and a gradual loss of sight. When finally he went to see a doctor, he was quickly examined and advised, in the manner of a parent breaking down a difficult concept for a child resisting sleep, that the sun in England is very different than in Jamaica, and that because he was relatively tall, he was closer to the sun than most. He died still undiagnosed, having been sent back to Jamaica by my grandmother (who could not be his full-time carer while nursing two toddlers and working) to be cared for by his relatives. A possible cause of his death was stroke, a treatable condition had he been taken seriously. The family got their story straight and were otherwise circumspect. What Fanon nailed was the cognitive dissonance one experiences in pursuing assimilation only to lose one’s identity and authenticity, almost as if there was no such thing as black, only nigger or white. Those who speak well are told by their colleagues and fellow students that they are no longer black, then sit on a train minding their own business only to scare a small child simply by being there.

Once, while working part-time in a restaurant, I was casually threatened with lynching by a white lady if my rosé wine recommendation was found by her to be inadequate. Whether she was joking or not (and I doubt she was, because she repeated it), I was the only black member of staff, so I can be certain that I was the only person whose presence would have provoked the idea in her mind of lynching. The threat of lynching made me hyper-aware of my (biologically male) body and my presence, and of how the character and knowledge I have built for myself can be wished away by someone who only sees the body, and their own idea of what my body is capable of and must be prevented from doing. We navigate life based on who recognises us on their own terms. Fanon, at 27, understood this deeply.

© Taíno Mendez

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

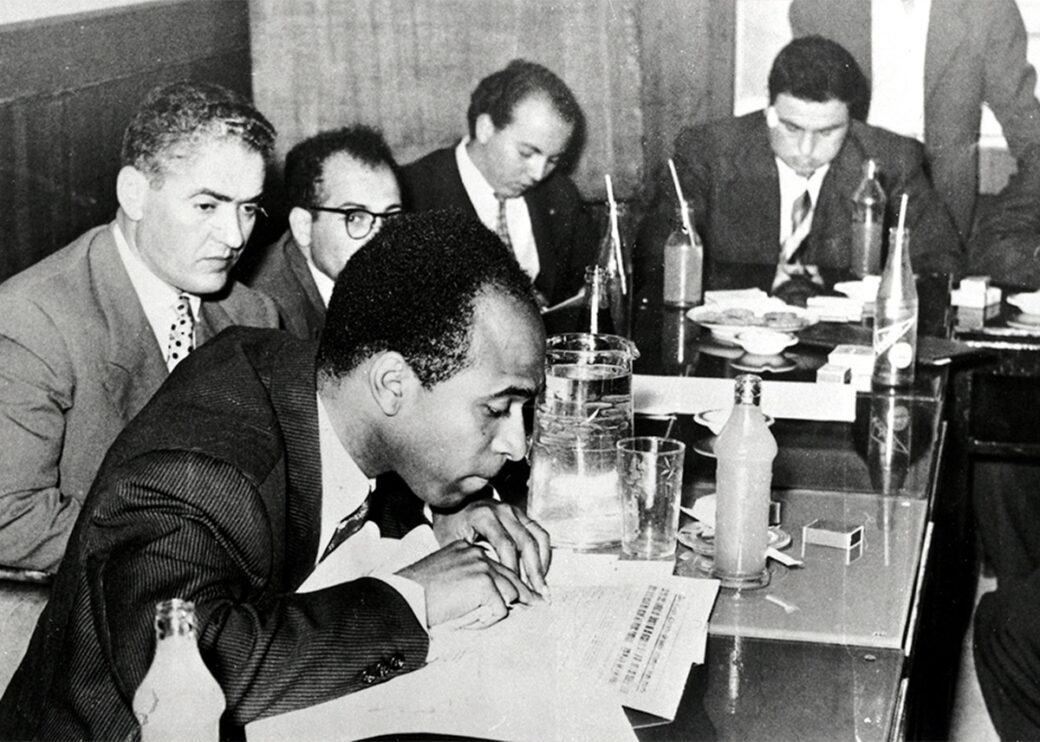

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.