Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

I read Frantz Fanon because I live in an ageing and timorous society. I’m one of those migrants that Europe is nervous about. I came to psychotherapy because I wanted to understand my own history, and what my inner experiences have to do with the outside world. I work in the field of mental health, where power and care are often overlooked. I’m interested in practical decolonisation and the formation of new, expansive national identities.

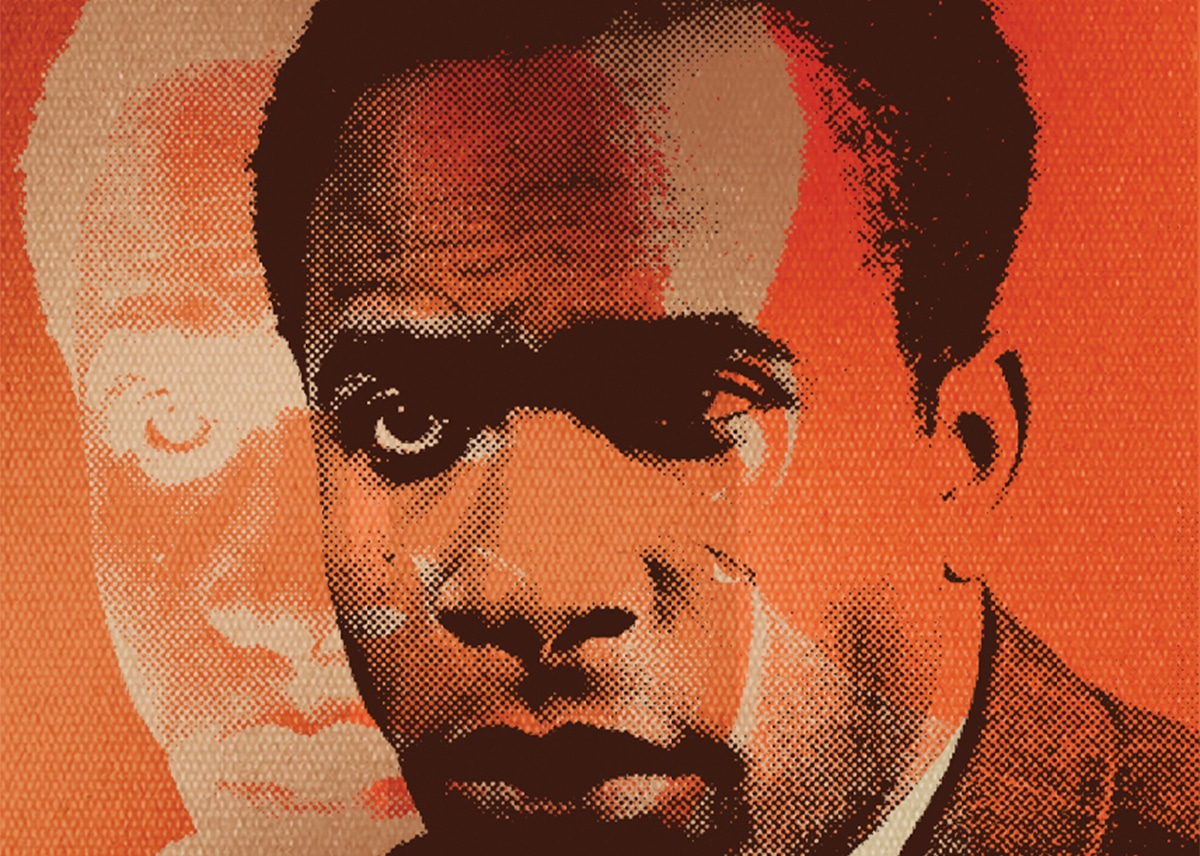

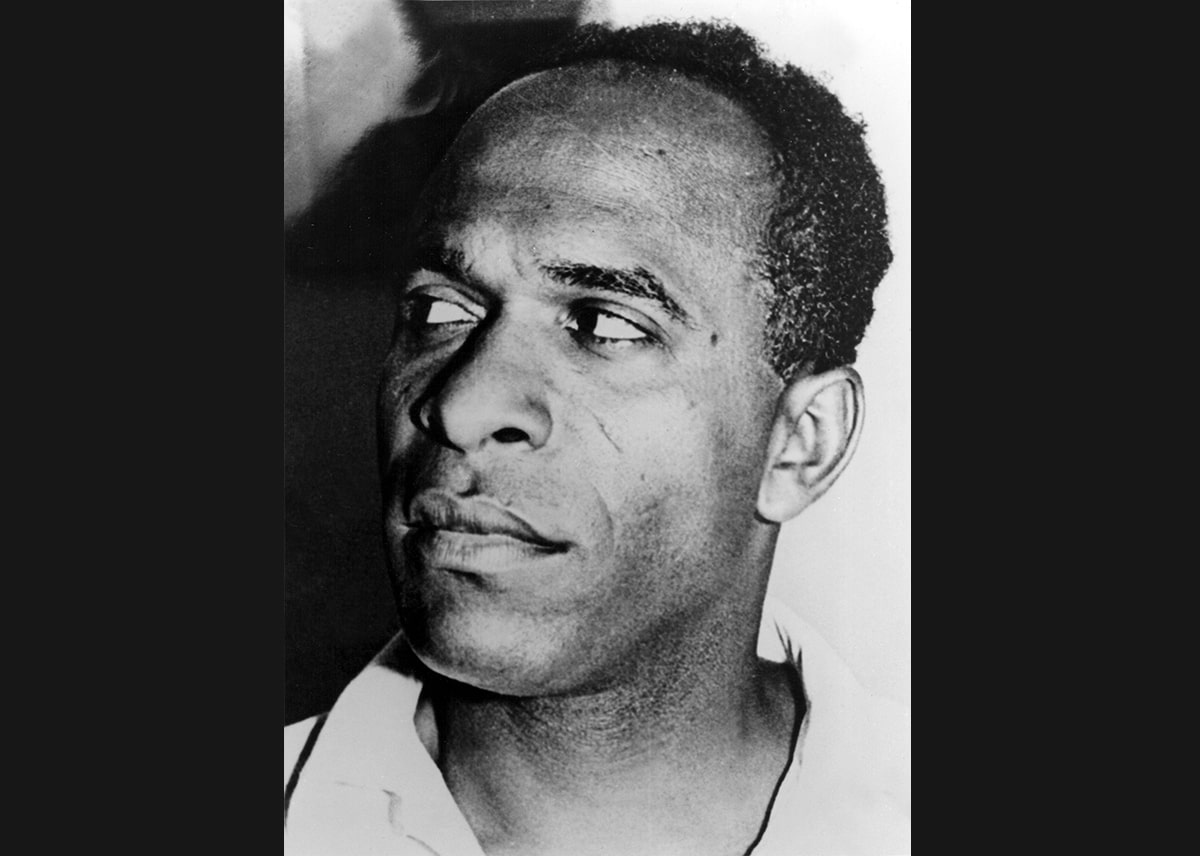

I find Fanon’s writing difficult, lyrical, and dry, but I’ve persisted long enough to read the major books several times. He has interesting things to say about the current behaviour of the African upper-middle classes, about racism, social therapy, the psyche, power relations, and gender in his native Martinique, and in France and North Africa. Fanon insists that the effects of French colonialism are radical, enduring, material, and psychological. He’s more interested in the mindset of colonisation than in colonial identity. He insists on a radical shift in power, and he refuses to rule out counter-violence.

Fanon brought to psychiatry his interest in difference. Progressive psychiatry looked for the causes of illness in the social and historical context of the individual. Fanon’s analysis paid attention to three groups which were categorised as subhuman: namely, Jews, blacks, and colonial subjects.

Fanon learned social therapy from the Catalan Marxist psychiatrist and resistance organiser François Tosquelles. Tosquelles thought the authoritarian power relations in the asylum made illness worse. His remedy was to give people within the institution some meaning, purpose, and agency over their lives. That innovation is still a radical departure from the norm.

Fanon is a phenomenologist. Much of what he asserts is based on his own experience and observations. He takes alienation, or Selbstentfremdung, seriously. He describes the workings of alienation through the categories of black and white, at the level of the body and in politics. I recognise its symptoms: the suspicion; the expectation of ritual humiliation; and then the exhaustion when my vigilance is rewarded by safety. I recognise the anger at an unmistakably racist incident, which arrives accompanied by a certain measure of relief before doubt sets in once more. You become strange to yourself.

The Wretched of the Earth (1961) has the clearest vision I have encountered of what can go awry after a revolution is won. In the most meaningful sections, I’m reminded of my birth country, and of my father’s hushed rage at the inefficient, censored, and heavily surveilled post-independence state by which he was employed.

Fanon explains to me the society in which I grew up. I’m part of the class he excoriates. The conditions he observes and describes are the laboratory which created my family and my birth country, Cameroon. He’d say we were the African would-be évolués who aspired to the status of the West Indian assimilated class, while they adopted white colonial dominant attitudes towards us.

Fanon is at his weakest on sexual identity and gender. If he had not been engaged in dismantling systems of hierarchical oppression, perhaps his description of homosexuality as a ‘colonial perversion’ might have been buried in the footnotes of commentaries about his work. Fanon’s writing about anti-colonial struggle is criticised for offering limited agency to women. In 1960, he met Simone de Beauvoir in Rome. De Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex had been in print since 1949. It seems to have made no impression on his work.

The most serious critiques of Fanon are from black feminists and feminists of colour. These critiques address the lack of depth and agency in the women he writes about. He seems anxious about fictional black female characters ‘lactifying’, or ‘milkifying’ themselves by jumping into bed with white fascists. As a student and then as a soldier, Fanon suffered from the widespread, crude sexual racism, where the toubab, or ‘white’ was preferred to the black Frenchman and the African.

Personally, I’m interested in looking at the current situation of women. The international school in Douala, Cameroon is next to the French supermarket, ‘Casino’. Entry to the street is controlled by private security guards armed with weapons that resemble semi-automatic rifles. There is a plethora of security companies to guard the property and the bodies of those who can afford safety. Most of the women I see at Casino are yellow-skinned, long-haired, and adorned with ultra-feminine accessories. Fanon would have condemned this aesthetic as lactifying.

Two long aisles in the Casino building are stacked with skin whitening preparations: creams, lotions, cleansers, and antiseptic soaps. When I was a teenager, we used to get our Topsyngel and Topicort from the Nigerian-run supermarket downtown or from the local pharmacy. The appearance of the women in the skin-lightening aisle at Casino is a side effect of a yearning which is echoed in Asia and the Americas. Skin brightening is a multibillion-dollar global industry. This is female desire in action. It’s not terribly different from the drag-adjacent aesthetic right-wing femme influencers and politicians adopt.

The desire of non-white women for the markers of middle-class whiteness is easy to caricature as ignorant or absurd lactification. It’s also a serious health risk. But skin lightening is one way in which women can use their appearance to telegraph their aspired status. If the desire for social advantage is automatically fed by a complex of inferiority, or by another pathology, then everyone who wants to change their class status is suffering from the same complex.

While I’m glad to have deeply engaged with Fanon’s work, I suspect he’d disapprove of my choices. I’ve settled in Europe. On the other hand, given what happened to African states after his death, he might have been moved to compromise. His writing reveals his enthusiasm for multi-ethnic citizenship, as well as his disinterest in Islam, Algerian traditions, and Arab nationalism. I don’t believe he could have stayed in today’s Algeria.

Some revolutions go wrong in Fanonian ways, but I’m still hopeful. It’s up to each of us to imagine a world that cares for all.

© Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley is a multilingual author, writer of poems, short stories, and non-fiction works.

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Roger Robinson

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.