Is english we speaking: African/Caribbean dialogue

Meeting the ogbanje

My first encounter with African literature was when I was fourteen or fifteen, living in Port of Spain, Trinidad, in the 1980s. I’d been an avid reader as a child, but as a teenager I made little headway with Austen, Dickens, or the Brontës. (I gravitated more to Americans: Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Miller.) When I read Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, then Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country, and Too Late the Phalarope, I felt a connection to these books that I hadn’t felt with the English novels, although I didn’t understand why.

In my mid-twenties, when I was starting to write, I came to Doris Lessing and J. M. Coetzee and I realised what had stirred me about these African novels: simply, that the physical reality of the characters’ lives was similar to the life I knew in the Caribbean. In Lessing’s The Grass is Singing, think of that little wooden house with the tin roof, the big dome of the unblinking blue sky above, that merciless blazing sun. In Things Fall Apart, see how much happens during the cool of the night-time, how people’s lives are organised around the need to avoid the midday heat. Though I’d never felt the need to ‘see myself’ as a Caribbean child reflected in a novel, I do remember, in Cry, the Beloved Country, reading about the red-brown dust that clings to the soles of people’s feet and feeling the shock of recognition, of thinking, ‘But – that’s just like us!’

In my early thirties, from around 2005 onwards, I was writing more seriously and noticing that new African/diasporic novels were gaining recognition. I read Nigerian British writer Diana Evans’ novel 26a partly as research, and partly because we lived in the same neighbourhood in London. Later, I read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Nigeria) and Petina Gappah (Zimbabwe) because I discovered that my editor at Faber had published both authors. What struck me was the clash of ‘old’ and ‘modern’ Africa – the houseboy in the opening chapters of Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun who’s amazed by the toilet and the fridge, for example: it was eye-opening to realise that both traditional and modern worlds co-existed in Nigeria, and that the society was large enough to accommodate that. In Gappah’s short story, ‘Our Man in Geneva Wins A Million Euros’, a Nigerian man in Switzerland responds to a scam email and ends up transferring his life savings to a fraudulent account and losing everything: again, it was the clash of worlds that struck me, and the human cost of individuals falling through the gap.

Overall, I have the sense that African writers are setting the pace in the fearlessness with which they approach potentially awkward subjects. In the novel Americanah, for example, I was impressed that Adichie so bluntly drew a distinction between ‘American blacks’ and African immigrants to the USA, exposing a cultural gap which perhaps had previously been denied. Another example is the (as I perceive it) change in the treatment of spiritual ideas: in 2005, in Evans’ book 26a, the Igbo concept of ogbanje spirit-possession is used as a metaphor throughout the novel, yet the word ogbanje is never used, and one character privately calls the concept ‘a load of had dock’. Fast forward to 2019, and in Akwaeke Emezi’s novel Freshwater, the ogbanje is now centre-stage, in person, controlling the narrative, and very convincingly. As a Caribbean writer, if there’s one thing I can learn from African literature, it’s to allow myself to be bolder in my own work and my own thinking: to meet the ogbanje head-on.

© Claire Adam

Claire Adam

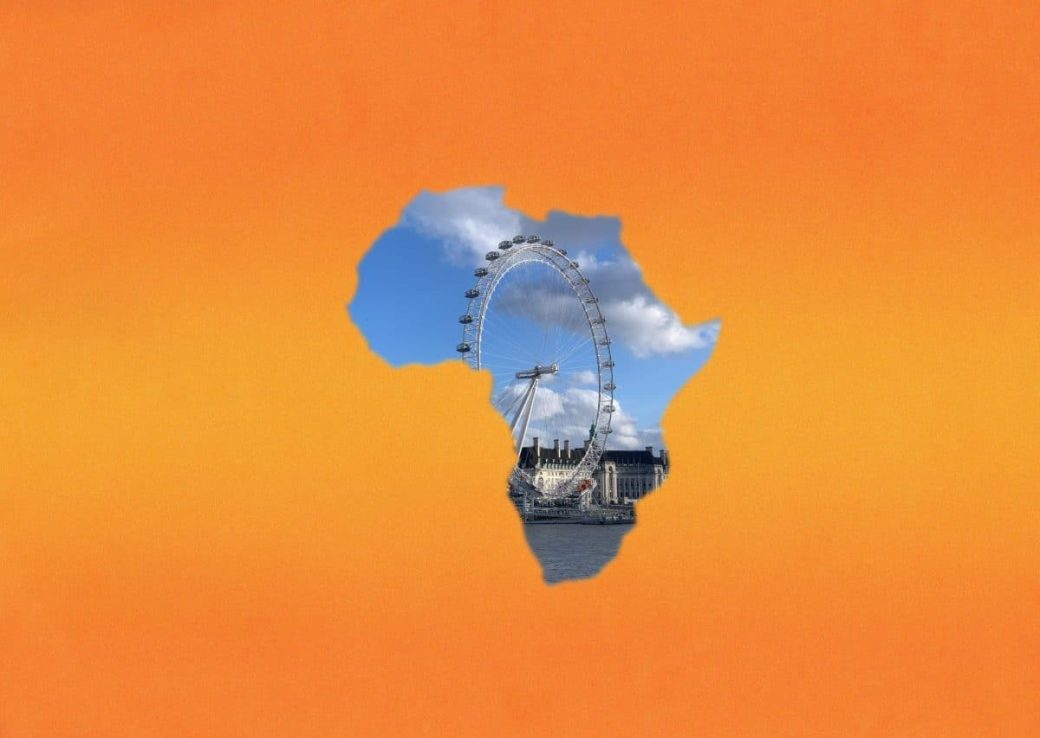

Claire Adam is from Port of Spain, Trinidad and now lives with her family in south London.

Is english we speaking: African/Caribbean dialogue

Snapshots taken along the way

Jane Bryce

A Fine Intuition

Billy Kahora

What is Africa to me?

Colin Grant

Who is ‘the other’ anyway?

Stewart Brown

Travelling Lines

Funso Aiyejina

A West Indian in Africa

Philip Nanton

Redemption is more than a song

Tendai Huchu

Together Apart

Robert Taylor

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Afro-Caribbean writer Frantz Fanon, his work as a psychiatrist and commitment to independence movements.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.