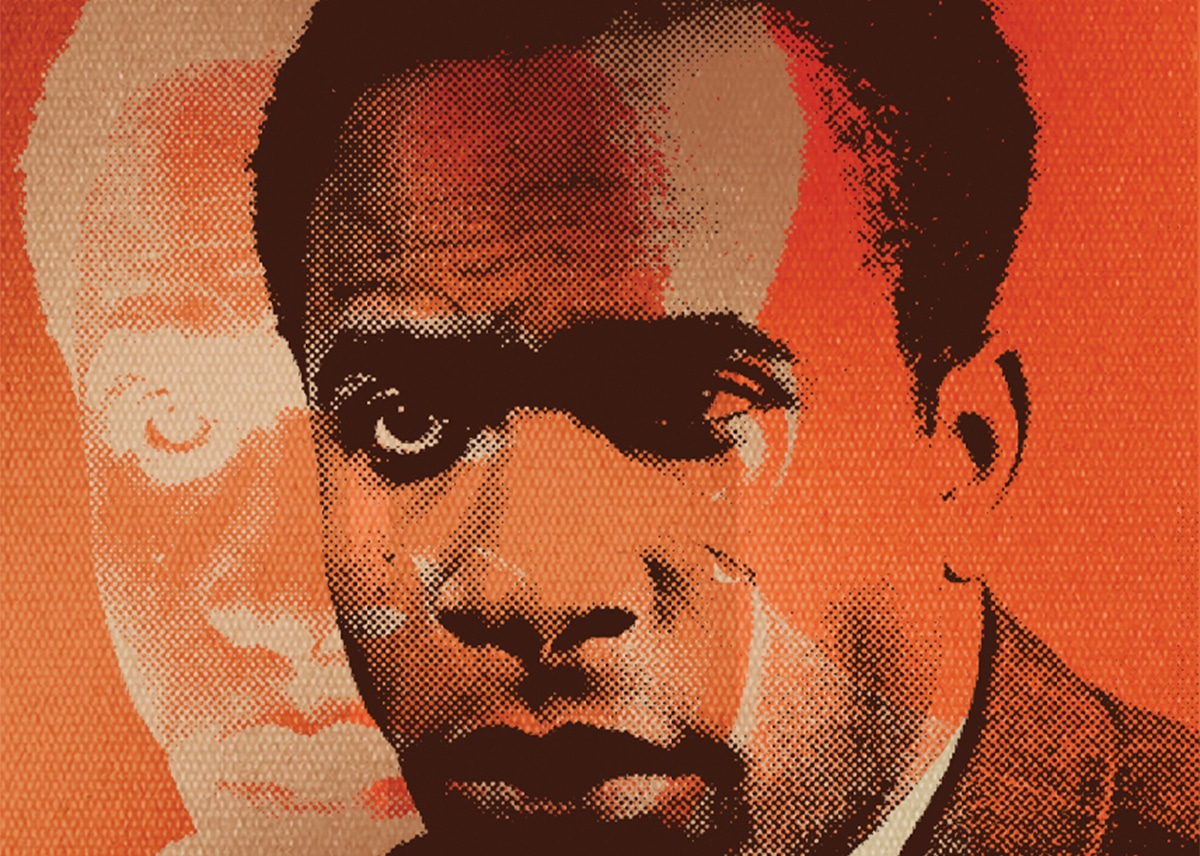

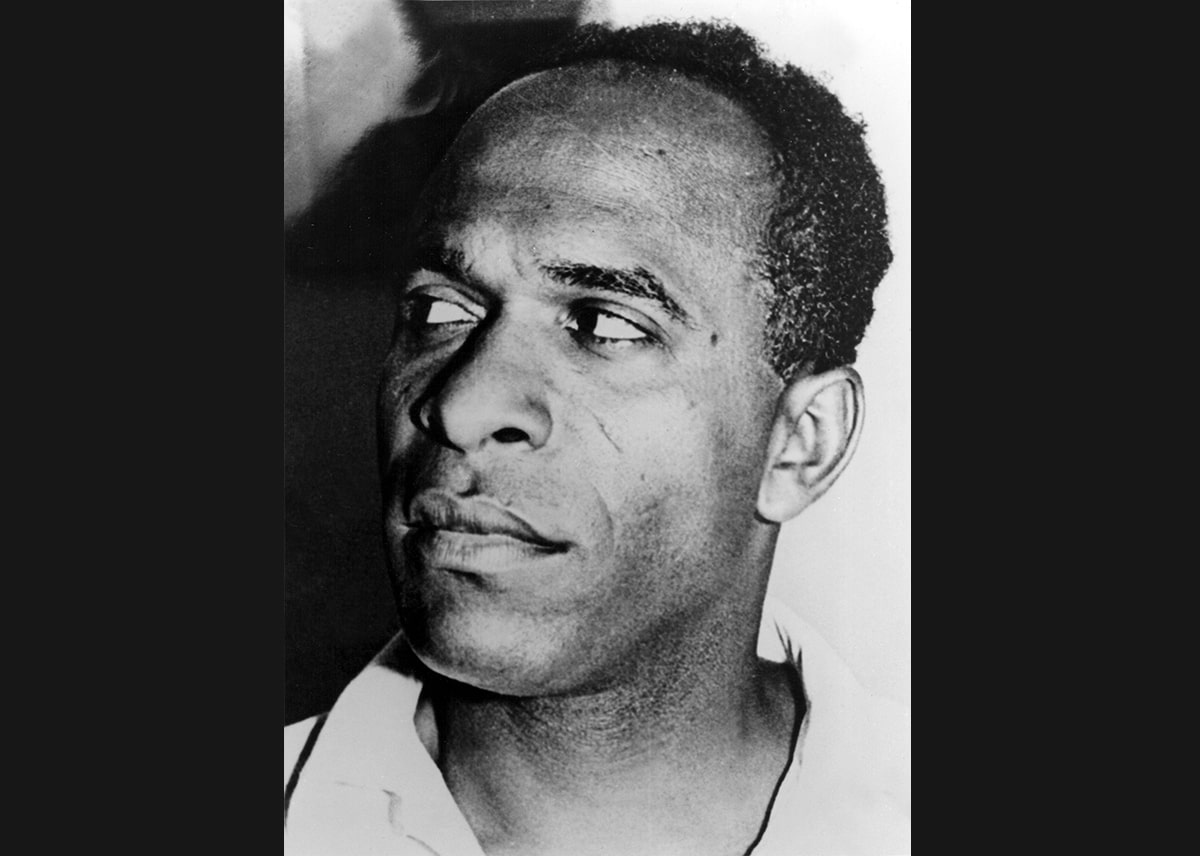

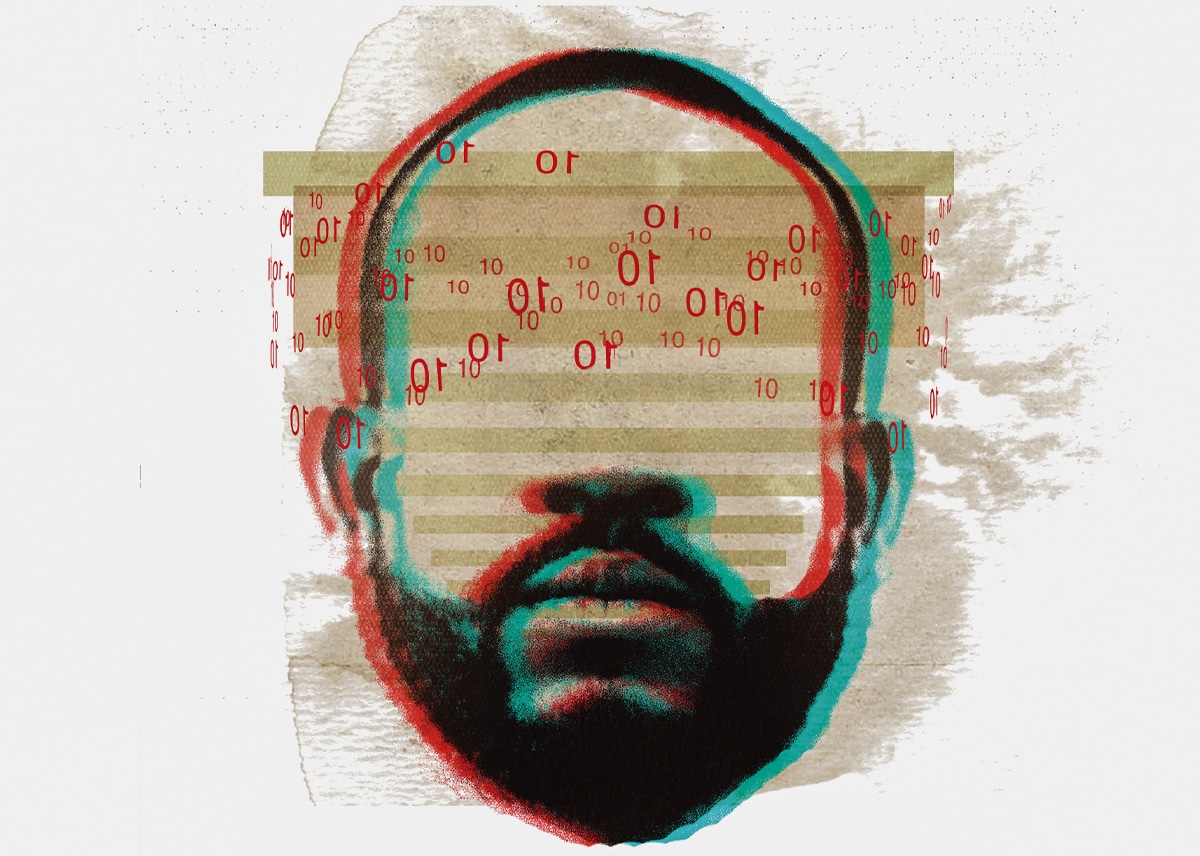

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

The racial allocation of guilt (after Fanon)

Once, at a writers’ festival in the late nineties, I was sitting at a table with some high-profile writers. The conference itself was a high-minded snoozefest, so I told everyone I was heading back to the hotel. To my surprise, most of the writers on my table, who by chance were all Black, decided to leave with me. That prompted one writer to whisper, with much concern, that we couldn’t all leave at the same time.

I asked why.

He said, ‘It will look bad.’

I asked, ‘To who?’

And that question forced him to confront the ludicrousness of his suggestion. The truth is, I knew what he meant: that it would look bad to white people, as if we were doing something wrong. I wasn’t angry with him for feeling that way. What I felt instead was a deep sadness: that he had to live his life with that kind of subservient awareness every day, and that only through my observation was he confronted with the weight of that struggle.

The same writer told me once without hesitation, that he was an Oxford man before he was Black. I tried to imagine what it meant, to be stitched into stone like ivy, the river punting its way through your bloodstream, the chapel bells loosening the body into certainty. But I also knew how quickly skin betrays the order of things; how, in the dark pane of a pub window, his face would arrive first, before the vowels of his speech, before the Latin in his step. There is always that moment when, walking into a room, and the air tilts toward what it thinks you are. Even here, among friends, I imagine the old dream: a banquet where the guests lean forward, smiling, and for a moment he believes himself invisible until one of them gives, without malice, an opinion on Black men that he grits his teeth to ignore. Oxford, I think, was never first. It was a mask held steady in the mirror, and behind it a man was waiting, almost gently, to be misnamed.

Fanon tells us: the colonised man is guilty before he speaks. His very skin is testimony. He inherits the crimes of conquest not as victim but as culprit, accused before the act, condemned without defence. In Black Skin, White Masks, he writes of the white gaze pinning him to the wall, demanding justification for his existence. This is not guilt earned. This is guilt bestowed, a transference of shame. The empire fires the gun, and the wound bleeds on the Black body, yet the finger of accusation points not to the trigger but to the chest that received it.

In the 2010s, my band King Midas Sound was getting very popular in Poland, Russia and Spain, which meant I was taking a lot of flights to tour, often returning on Sunday evenings through Stansted Airport. At the time, I was full of main-character, front-man energy: broad-brimmed hats, a full beard, and snakeskin boots. Let’s just say I dressed distinctively, to say the least.

One time, I came through the passport scanner and was accosted by a short, plain-clothes policeman who identified himself and asked me to follow him. By a door to a side room, he proceeded to fire off question after question, with no logic in their order or intention. I was tired but calm. After making me wait 20 minutes while he disappeared with my passport, he returned and said I could go.

The next week, the same plain-clothes officer stopped me again and went through the exact same process. It felt like Groundhog Day. Again, I was tired, but I kept calm, and again, he eventually let me go.

The following week he stopped me for a third time, the exact same officer. I asked to see his supervisor. He reacted as if my request was some sign of anger or guilt. I told him plainly that this was the third time in three weeks that he had questioned me. He looked at me as though I’d fabricated the whole story. I refused to answer his questions without his supervisor present.

At that moment, one of his colleagues walked up, whispered something to him, and suddenly he handed back my passport, saying I was free to go. I can only assume his colleague remembered me from the previous two times and recognised his bias. And I can only assume an escalation on my part towards his supervisor would not be desirable.

Lasso: Each time, through Nothing to Declare, my body remembers its own guilt. Even when innocent, I feel watched, as if the mirrored glass has eyes that hunger. It’s the table, too, the way it waits for your belongings like an altar stripped bare, where nothing is meant to be cherished. Then the lasso rope comes. A new weapon among the others – taser, pepper spray – and I hear it first, a sound like a whip cutting the air clean open. The lasso’s loop falls, almost tender, closing around my arms, a kind of embrace, except it drags only me sideways, in front of everyone. Questions, questions, spill: Where do you come from? Where are you going? When were you born? Their voices work on me the way shame robs your stature. The next time, another airport. And again the rope with its whoosh through air, its swift tightening, and the pull. I begin to understand: this is the shape travel takes now, a lasso loop in the air, always finding its mark, tightening and dragging.

Fanon believed decolonisation must be a cleansing, a wresting back of the right to innocence. But what does innocence mean in a world that insists on your guilt? Even joy can feel like defiance. Even laughter can be cross-examined. The colonised carry a double task: to live, and to justify living.

I’m taking a bus to the airport, and the driver puts my bag, along with many others, into the storage at the bottom of the bus. When I arrive, I calmly take my bag out, and a young white woman in slippers, baggy pants, and a vest top runs up to me and tries to pull my bag away, shouting, ‘No, no, no!’ She calls out, ‘Help, he’s stealing my bag!’ and several white men walk toward me. I calmly show her the tag on my bag, and she just walks off, no ‘I’m sorry,’ no ‘I made a mistake.’ The men return to their business with no shame in their accusatory eyes. Just me, with my bag, and this weight I have to carry.

Colonial violence is a theft of blame. It moves like smoke: unseen yet suffocating. The police officer who stops me does not say I am guilty; he simply acts as though I am, and the action makes it so. The assumption becomes the verdict. This is how power works: it transforms suspicion into evidence, and evidence into sentence, without the inconvenience of proof. Fanon knew this: ‘The Negro is comparison.’ His very being is a trial without jury.

© Roger Robinson

Frantz Fanon: revolutionary psychiatrist

Editorial

Colin Grant

From the individual to the collective

Zebib K. Abraham

The person and the nation

Taíno Mendez

Blida, Algeria, 1953

Ekow Eshun

Writing the wound: politics, poetics, psychiatry

Clementine Ewokolo Burnley

On entering the zone of being

Chitra Ramaswamy

Brown skin, white mask

Khaldoon Ahmed

Alternative destinies

Isabelle Dupuy & Zoe Mohaupt

Inglan mad dem

Colin Grant

Illuminating, in-depth conversations between writers.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

The series that tells the true-life stories of migration to the UK.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

Amazon Music

YouTube

Other apps

Creative women in Iran and the diaspora reflect on the state of Iran and dream for the future

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

A six-part audio drama series featuring writers with provocative and unexpected tales.

Listen to all episodes

SpotifyApple Podcasts

YouTube

Reggae Story

Hannah Lowe reads her poem, 'Reggae Story' inspired by her Jamaican father, Chick. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.

The City Kids See the Sea

Roger Robinson reads his poem, 'The City Kids See the Sea'. Directed by Matthew Thompson and commissioned by the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation.